The October 2019 Protests in Lebanon: Between Contention and Reproduction

The Lebanese power sharing consociational system has structurally engendered recurring protest cycles: student mobilisations, labour and union mobilising, left-wing collectives, as well as a more routinised associative sector. In a long temporality, and looking at these movements in a longitudinal approach, changes they appear to be seeking appear to be marginal or quite limited, which may lead to the observation that contentious movements play the role of mere relief outlet within the system they are challenging, hence, contributing to the permanence of the social and political structures they are challenging.

The past year has witnessed the emergence of a mobilisation cycle in the country that displays a continuity with previous forms of organising, although unprecedented in terms of its geographical spread over the territory.

To understand how this current protest cycle unfolds, its dynamics, and limits, we propose to consider how social actors “move” in a contested, competitive, ever-shifting and evolving arena, rather than a homogeneous one. We rely on a three-fold conceptual approach that focuses on the analysis of the interactions and dynamics between actors, and the strategies they employ: persuasion, coercion, and retribution.

To cite this paper: Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi, Léa Yammine,"The October 2019 Protests in Lebanon: Between Contention and Reproduction", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2020-07-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.001.80000

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/october-2019-protests-lebanon-between-contention-and-reproduction

Introduction

The Lebanese power sharing consociational system has structurally engendered recurring protest cycles: student mobilisations, labour and union mobilising, left-wing collectives, as well as a more routinised associative sector. In a long temporality, and looking at these movements in a longitudinal approach, changes they appear to be seeking appear to be marginal or quite limited, which may lead to the observation that contentious movements play the role of mere relief outlet within the system they are challenging, hence, contributing to the permanence of the social and political structures they are challenging.

The past year has witnessed the emergence of a mobilisation cycle in the country that displays a continuity with previous forms of organising, although unprecedented in terms of its geographical spread over the territory.

To understand how this current protest cycle unfolds, its dynamics, and limits, we propose to consider how social actors “move” in a contested, competitive, ever-shifting and evolving arena, rather than a homogeneous one. We rely on a three-fold conceptual approach that focuses on the analysis of the interactions and dynamics between actors, and the strategies they employ: persuasion, coercion, and retribution.

A. Genealogy of the contemporary social movement: a longitudinal look at the October protests

The student movement has spearheaded social movements in the 70s notably around the Lebanese University (Favier, 2004). However, it disintegrated during the civil war (1975-1990). The end of the civil conflict witnessed a revival of campuses as protest spaces, with the creation of the “independent leftist collectives” (al-Majmuʻât al-yasâriyya al-mustakilat) in the 1990s such as Bila hudûd / « No Frontiers » at the American University of Beirut (AUB), « Pablo Neruda » at the Lebanese American University (LAU), « Direct Action » (al-‘Amal al-mubâchar) at the Balamand University, « Tanios Chahine » at the Saint-Joseph university (AbiYaghi, 2013). These collectives positioned themselves in the political landscape of post-war Lebanon as opposing the main two hegemonic political axes which consisted of a securitised approach supported by the Syrian occupation on the one hand, and on the other, neo-liberal economic policies championed by Rafic Hariri. It is within these collectives that a generation of activists was incubated and socialised on political and social activism (AbiYaghi, 2013).

Another space for the incubation for generations of activists, has been the civil society sector. This sector, which dates back to the Nahda era (Karam, 2006) and which encompasses a wide array of actors, saw its mission being realigned towards relief, and services during the civil war. While the post civil war era saw the emergence of expert and advocacy NGOs, their positioning as either service or expertise providers for state actors, has led them to downplay the contentious positioning and role they could play (McAdam Doug, Tarrow Sydney, Tilly Charles 2001, Dynamics of contention, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p. 5.; AbiYaghi 2010, p. 71-75.) Civil Society in Lebanon is thought to operate in a rather liberal setting compared to other countries in the region, given the rather lenient legal framework governing the creation of non-governmental organisations. However, that does not take into consideration the various restrictions that can be encountered in practice, whether in the granting of registration approval forms, the scrutiny over the work of NGOs for state bodies and banks, and the limitations of local organisations operating in the global aid economy1. In spite of operating in confined “molds” (AbiYaghi, Yammine, and Jagharnathsing, 2019), the associative sector has still contributed to nurturing a space for the socialisation of individuals, acquainting them with activist modes of action.

These various avenues of activism have contributed to a period of activism “effervescence” in the late 1990s in the country (AbiYaghi, 2013) and to the emergence and crystallization of “new” leftist collectives. The latter, being more political collectives, have mobilised around contentious issues in Lebanon, but also around more global issues, echoing international movements against neolibral globalisation. This period witnessed the emergence of a nebula consisting of various groups, such as independent leftists collectives (Tullâb chuyu’iyûn expliquer); alternative media collective such as Indymedia, al-Tajamuʻ al-chuyuʻi al-thawri, al-Tajamu’ al yasâri min ajl al-taghyîr), al-Khatt al-mubashar, al-Jam’iya al-lubnânîyya min ajl ‘awlama badîla Attac Lebanon, among others.

Indymedia poster in 2004.

Those groups positioned themselves on opposing lines to traditional and establishment party structures. While some among them embarked on a journey to create an alternative partisan left leaning structure (the Democratic Left Party - Harakat al-yasâr al-dimucrâtî), this process also saw new lines of contention between activists (those closer to the communist youth - Tullâb chuyu’iyûn) and other collectives).

The year 2005 was indeed a pivotal moment in Lebanon’s recent history, as the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafic Hariri on February 14 galvanized crowds in two main axes, named after the dates of their respective massive protests:

- March 14, the culmination of mobilisations by a diversity of groups on the right and left sides of the political spectrum against the Syrian occupation, starting in 1990 and that gathered namely Future Party, Free Patriotic Movement, the Phalangist Party, Lebanese Forces, Democratic Left Party, and other left leaning collectives and groups;

-and March 8, which articulated on opposing lines and that expressed support for Syria and which included mainly Amal Movement, Hezbollah, the Lebanese Communist Party.

The two axes later saw ruptures and reformations, but they structure, till this day, the political landscape.

In parallel, we can also look at the women’s rights and feminist movements that started early last century and took more shape in the 70s and 80s, concomitantly with the global debate and international conferences on human rights and women’s rights. Up until the mid nineties, these movements fought for expanded political rights, although they were still aligned with establishment political parties ideologies. Thus, women’s organisations failed to translate values they defended into their own discourse, which was still structured conforming to a sectarian system2. After the nineties, the trend was to institutionalise, in what is known as “NGOisation.” This impacted their structure but also the content of their discourses, which adopted a more global aspect, more in line with INGOs and donor organisations. This, however, led to continuous dependency on donor funding, and shaped local actors’ agendas and priorities (Mitri, 2015), a trend that is apparent with all CSOs work and not just limited to the gender sector. Since the 2000s, in parallel to the continuous development of NGOs, activist collectives on bodily and sexual rights came about, and distinguished themselves from previous activists by adopting a clearly political discourse, and emphasised intersectionality and identity politics.

From this perspective, a generation of social and political activists has been socialised to engagement and organising at the intersection of the three fields: student activism, civil society organisations, and political collectives.

B. In search of a “localised” frame of contention

Research on collective action showed how in the 1990s, collectives and activists mobilised around three main overarching causes: the denunciation of neoliberalism (that crystallized in the early 2000s in alternative or antiglobalisation stances), anti-imperialism, and anticonfessionalism (AbiYaghi, 2013). This frame alignment has been prevalent among these collectives and activist circles during the past two decades, and is still prevalent to certain extent today.

These causes have notably been illustrated in mobilisation against the lebanese civil war in support to families of victims of enforced disappearances, as well as the refusal of the imposed post war amnesia (“Tendhaqar ta mâ ten’âd” campaign in 1997 for example), the war on Iraq in 2003 (the no war no dictatorship, (lâ lil-harb, lâ lil-dictaturiyyât), and in 2006 during and in the aftermath of the 33 days Israeli war on Lebanon.

From campaigning and lobbying to relief coordination, notably during the Nahr el Bared conflict in 2007 that witnessed limited mobilisation, but rather consecrated another shift in the modes of actions of activists towards a role of coordination of aid, and of relief provision3.

In parallel, the contestation of the economic system has also been prevalent in various cycles of mobilisation, with activists denouncing the privatisation of public services, for example the Lubnân mech lal-bay’ (Lebanon is not for sale) campaign in 2006-7, and the Dawla aw ichtirâq (in reference to state-provided and private generator electricity) campaign in 2008-9.

Lastly, the denunciation of the consociational system has been crosscutting in previous mobilisation cycles, such as the Laique Pride (masîrat al-‘almâniyîn) in 2009-2010, and the subsequent movement demanding the downfall of the sectarian regime in 2011, in the vein of the Arab revolutions.

Campaign poster of the “isqat an-nizam at-ta’ifi” movement from 2011 to commemorate the start of the civil war (on the 13th of April 1975).

The movement mobilised various collectives as well as political parties over the course of a few weeks during winter and spring 2011 (leftist parties and collectives such as the Socialist Forum, the Union of Lebanese Democratic Youth, the youth movement of the Lebanese Communist Party, the Democratic Collective, mainly composed of former activists from the Organisation for Communist Action in Lebanon (OCAL) in Saïda; the Secular Club at the American University of Beirut) and civil society organisations (such as the Civil Society Current). However, it stumbled on divisions in framing the movement mainly between informal groups and more institutionalised political parties, with divergences on whether to call for the downfall of the reform of the regime, as well as regarding the stance vis-à-vis political leaders or the Syrian conflict (AbiYaghi and Catusse 2014). Nevertheless the movement led to the creation of several smaller collectives that are still active today such as the Haqqî ‘alayyi (‘My right’) campaign in Beirut, the Tripoli Without Arms campaign, the Civil Forum in the Beqaa, bringing together secular and leftist activists from different villages and towns, and the ’Amal mubâshar (Direct Action), a coalition of independent activists in Beirut, Beqaa, and the Chouf (AbiYaghi, 2012).

Another cycle of protests shook the streets of Beirut in 2015. It started with the mobilisation of local residents and a few ecological activists as “not in my backyard” movements (NIMBY), notably in the small locality of Barja in the Chouf district, close to the Na‘ameh landfill, as of 2014. This movement grew first on social media and then on the streets of the capital. While the ecological issue was the main overarching demand, the movement instigated and rallied people behind demands for accountability and against corruption, denouncing the practices of collusion between private companies, the government, and political leaders and figures (Bekdache 2015; Dot-Pouillard 2015).

Indeed, activists mobilised to provide technical solutions for waste management, all the while framing their demands by denouncing corruption, and its links with the consociational system, around collectives such as “you stink” collective (mainly formed by independent and civil society activists) or the left-leaning collective “badna nhasib” (“we want accountability”) which included political parties like the Lebanese Communist Party’s “Ittihad ash-shahab al-dimuqrati” (“The democratic youth union”), “Harakat ash-Sha’ab” (“The people’s movement”), Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) and the Ba’ath Parties. Other smaller groups emerged, such as ‘ash-shara‘a (“to the streets”), which gathered activists from the moribund Democratic Left Movement; “thawrat 22 ab” (revolution of August 22), a group of independent leftist activists, the “Feminist Bloc”, notably around the feminist collective “sawt an-niswa”, and “ash-sha‘ab yurid” (“the people want” that includes grassroots movements and collectives, notably the Socialist Forum, a Trotskyist party.

Some of these collectives and groups focused on technical and ecological aspects of the garbage crisis, while others linked discursively the collusion of private interests with the Lebanese government, and establishment parties. Even though the movement gained a certain momentum across the territory, allowing for a certain decentralisation of mobilisations, its main protagonists and animators remained Beirut based experts and activists with prior activist experience. Even though the movement gathered various ideological leanings and mobilised around the common denominator of anti-sectarian narratives, it quickly stumbled on the “sectarian ghost” which manifests in the framing of the movement illustrating political and sectarian leanings of the protesters themselves (AbiYaghi, Catusse, Younes, 2017). This is notably apparent in the slogan killun ya‘ni killun (everyone means everyone), in which “except my leader” is implied, which ultimately contributed to the disintegration of the movement.

With the 2015 protests going beyond waste managements and framing demands on corruption and poor governance, the movement led to an engagement in the municipal elections of 2016, notably with the formation of the Beirut Madinati group that, however, presented itself as an independent and politically unaffiliated group concerned with environmental and socio-economic issues, and the quality of daily life in the capital. Although unsuccessful in the elections, the experience was echoed in other regions with similar groups emerging and participating in formal representation processes, such as Baalbek madinati for example.

Ahead of the 2018 parliamentary elections, candidates organised “new” lists that gathered individuals from previous “civil society” movements. Still, these lists failed to gain the trust of citizens and present a viable alternative; independent civil society actors only won one seat in Beirut I (Tavana and Parreira, 2019).

The last two protest cycles show some differences: the 2015 movement being more “technical”, focused on environmental issues as well as the denunciation of poor governance and corruption, while the 2019 mobilisation was from the outset, political. Narratives, slogans, and demands of protestors made clear linkages between the consociative sectarian regime, the pervasive collusion of private and public interests, and rampant nepotism. In this sense their grievances provided the mobilisation with a political stance and framing of the movement.

Both cycles however carry similarities, and show a continuity among each other, as well as previous mobilisations. Interestingly, the “killun ya‘ni killun” slogan was adopted from the onset of the 2019 protests. These cycles stumbled for various reasons notably due to their often contentious relations with establishment political parties. For example and interestingly, the “killun ya‘ni killun” slogan was adopted from the onset of the 2019 protests, and while seemingly appearing to be less controversial, many protesters still felt their leader was exempt from it. Nevertheless, the processes instigated by the 2015 and previous movements have led up to the most recent cycle of mobilisation consecrated by the 17 October Protests of 2019.

C. The october 17 movement as the crystallization of a multi-organizational field

Looking at mobilising structures documented in Lebanon Support’s mapping of collective actions4 and its interactive graphs5, in the most recent years, it appears that workers groups and affected groups (including NIMBY) are amongst the most active. Indeed, between 2017 and 2018, half of the collective actions mapped were led by either one of the two groups, closely followed by informal groups and collectives that constituted 20.1% of total collective actions mapped. In the context of Lebanon, where labour movements and unions were undermined by the state and its parties with attempts of co-optation (Léa BouKhater, 2019), it is noteworthy to see workers always attempting to mobilise. The category of workers groups used encompasses, in addition to traditional structures such as unions, employees outside of such structures, and others mobilising around labour and employment more informally, denoting the prevalence of labour issues in the collective actions landscape. 2019, however, saw the high prominence and quasi majority of actions being led by informal groups and collectives (86% of total collective actions mapped in 2019), as this year saw the rise of many new collectives and groups mobilising in Beirut and the regions as part of the October Protests.

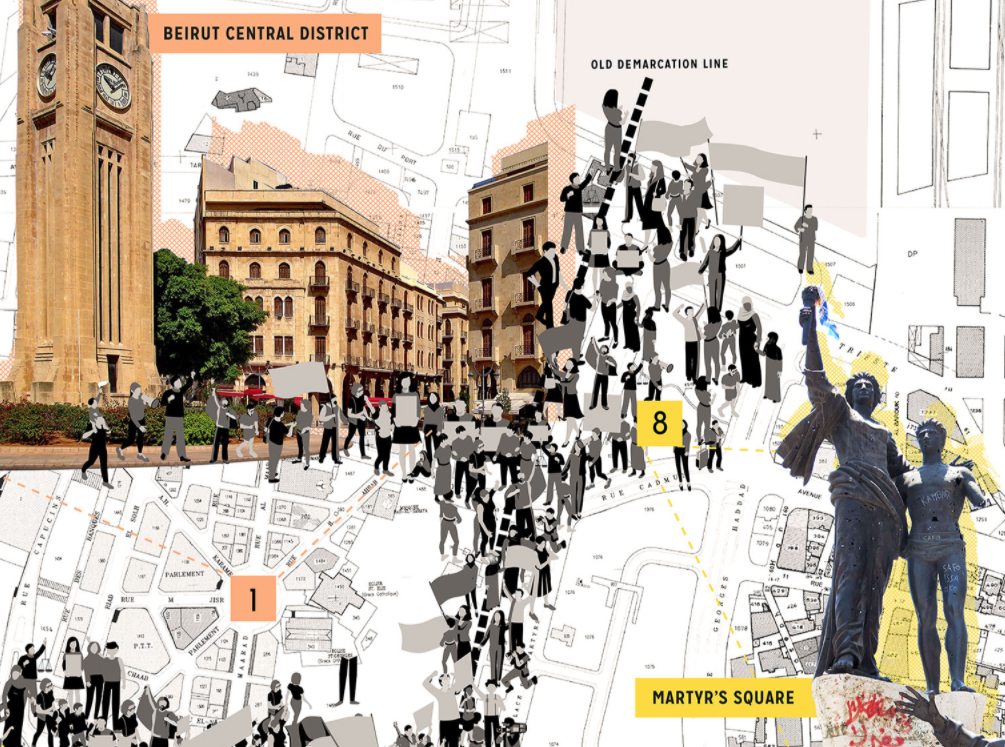

On October 17, 2019, protests erupted organically in Beirut, and grew in size and reach over the following days. The ensuing social movement is now known as the “October protests”. While the punctual trigger for the mobilisation may have been a decision to tax Voice Over Internet Protocols (such as Whatsapp), protests rejected austerity measures, regressive taxes, rising public debt, growing inflation, and deteriorating living conditions, issues that were at the heart of mobilisations in Lebanon since at least 20156. This social movement underlines a crisis of political legitimacy and trust, and is to be considered in the context of an increasingly constrained democratic and civic space.

While the October Protests seemed to be led by “anonymous” collectives, it still encompassed a diverse range of actors, including political parties, CSOs, activists, etc. in multiple, and sometimes conflicting, arenas. This makes way for potential cooperation across spheres, but it can also lead to dissension and conflicts as different actors would have different agendas, modes of action, strategies, among others. From this perspective, we consider actors involved in contentious politics as non static and fluid. Rather than considering the “state”, we refer to state actors for example, as a web of intertwined actors that interact formally and informally and fulfil a state function. Similarly, social movement actors cannot be considered as static, always in a protest position vis-à-vis the “state”, for example some contentious actors may be called to collaborate with state and public institutions, or even fill some public functions.

Hence, “a strategic perspective, by highlighting who actively does what, forces us to ask if both “movements” and “states” are not a bit of a fiction, implying a unity for each that does not really exist (McAdam et al. 2001; Duyvendak and Jasper, 2015).

Definitions, contours, roles, and functions of various actors in a polity are porous and constantly shifting.

To understand the various strategies adopted by activists, as well as how these same strategies contribute to hindering the movement, we propose a three fold conceptual framework: persuasion, coercion, and retribution (Duyvendak and Jasper, 2015).

This framework allows actors to understand their interactions with the state, as well as their interactions among each other, as well as other actors. It is also a tool that allows us to grasp how, based on these interactions, actors make (intentional or unintentional) strategic choices.

We can thus “achieve a dynamic picture of politics, in the plans, initiatives, reactions, countermeasures, mobilizations, rhetorical efforts, arena switches, and other moves that players make” (Jasper et.al., in Della Porta and Diani, 20157). In turn, this approach also gives insights on how actors, and their decisions, and actions, can be shaped by others, as well as well as their own adopted strategies. The conceptual framework identifies the three strategies of persuasion, coercion, and retribution that can be used by all actors involved, including for example states and their policies that can exert repression or coercion towards social movements, or social movements themselves using coercion or retribution for example.

- Persuasion

Persuasion is one of the main tools actors generally use to reach their goals. One could (depending on the view point) refer to it as “ideology”, “soft power”, “awareness”, or “sensitisation”.

The October 2019 protest movement, similar to others, relies heavily on persuasion as a main strategy of action, mobilisation, and dissemination. The movement calls upon creative and innovative ways to create awareness around socio-economic issues, denounce corruption, and spread messages about planned protests and actions. Activists and collectives used visual formats (pictures, infographics, videos) on social media platforms, that while messages were common, reflected various visual styles since each group relied on its own ways to produce these visuals, rather than relying on professional “productions”. Activists also relied on messaging apps such as Whatsapp and Signal to communicate, plan, and strategize. Hashtags were deployed as calls for action, for example al quwwa lil nas (power to the people) reiterated calls for alternative political systems that would put people and their needs first, and reclaiming people’s agency in decision making, in contrast with the consociational system that has imposed a sterile notion of democracy.

Posters from the 2019-2020 social movement.

The protest movement also witnessed attempts of alternative organising with collectives adopting horizontal, and non hierarchical structures, even though previous attempts by similar collectives notably in the early 2000s had shown limits to this type of organisational structure as shown in AbiYaghi, 2013. Indeed, the “tyranny” of structurelessness (Freeman, 1970) typically paves the way to the emergence of informal leaders. The adoption of flat structures has led to the absence of a centralised “official” leadership that would speak or represent the whole movement. However, previous research illustrates how in reality unofficial and informal (and oftentimes non-democratic) leaders tend to emerge in these types of non-hierarchical structures.

- Coercion

Coercion is a tool utilised by actors using violence, whether symbolic or physical.

While the “revolutionary” ebullition has imposed a sort of a Marxian imperative to organise, sometimes in a mimetic emulation vis a vis other revolutionary processes in Tunisia or Sudan, this has led to a certain extent to the creation of empty organisational structures that are more cosmetic than democratic and participatory, illustrating the limits of organising as persuasion strategy, but also the underlying tendencies to reproduce the mere system that was being criticised.

In this perspective, coercion can be exerted by informal/ undemocratic leaderships towards members of the groups and collectives; typically informal leaders in flat structures are oftentimes men, with important social and cultural capital.

Coercion was not only exerted on social movement actors; it was also exerted within the same social movement arena. The latter, as mentioned earlier cannot be considered as static nor homogeneous. The actors’ diverging forms of organising, ideologies, grievances, socio-economic and confessional backgrounds, and mode of actions are patent within the movement. Episodes of labelling categories of protestors as “infiltrators”, by stressing on their primary religious or partisan affiliation, or their (often disenfranchised) social background merely reproduce the segregational ethos of the political system these actors are mobilising against (as shown by AbiYaghi, Younes, and Catusse, in 2017). Similarly, lines of rupture based on the modes of action adopted by groups, illustrate contentious dynamics within the movement. Narratives, and practices of dissent between what is considered “violent” and “peaceful” modes of action and protests, with their underlying categorizations of activists along socio-economic and sectarian lines, end up reinforcing the status quo and system.

On the other hand, the state attempted to negotiate with the social movement, by trying first to assign a leadership to it in order to be able to identify and contain the movement. Representatives of the social movement were repeatedly invited for discussions, with some being auto-proclaimed or selected by the state. However, protesters refused to recognize any group or persons as representative of the overall movement sticking to the mantra of ‘no leadership’. While this strategy was at the advantage of the social movement at first, with the crisis lingering and compounded with an economic crisis, this proved to have a counter effect, and limited the social mobilisation’s longer term impact.

Coercion can also refer to the use of violence. The social movement was met with unprecedented use of force and repression by the state – including heavy use of tear gas and rubber bullets (often directly and at short range), water cannons, arrests8 – further establishing an already shrinking civic space that has been witnessing detention, arrets, and increased scrutiny on civil society.

The below infographic by Lebanon Support illustrates the detention of activists and bloggers over the span of a few months in 2018.

“Crackdown on Social Media by Lebanese Authorities.” Infographic by Lebanon Support, available on: https://civilsociety-centre.org/content/crackdown-social-media-lebanese-...

This shrinking space is also exemplified by limitations in laws, for example the law of access to information that activists could rely on in demanding greater transparency was hampered in 2019, as more than two years after the law taking effect, a body overseeing its implementation is yet to be established and many public administrations still lack the infrastructure and resources to respond to information requests9.

- Retribution

The third part of the framework refers to the gains and gratification, whether material or symbolic, of actors and players, and how these shape their decisions and actions.

A longitudinal look at the actors involved in social movements, as well as more institutionalised organisations in the civil society space, shows the multi-positionality they display. This multi-positionality may consist of the successive or concomitant roles they play and/or posts they occupy throughout their trajectory or “activist career”. Hence, many actors find themselves at the intersection of professionalised roles within civil society organisations, but also, leading actions and activism on the ground. This multi-positionality may facilitate interconnectedness within the overall multi-organisational civil arena, with exchanges between professional organisations and more grassroots ones occurring organically. Yet, narratives and praxis of the actors themselves rather often illustrate a dynamic of tension between the two roles: in a nutshell between “professionalised” or “paid” forms of engagement, and “volunteer” ones.

Previous research had shown how, for activists, working in the associative sectors was lived and considered as a form of public service (AbiYaghi, 2013). This can also be accompanied by symbolic gratification consisting of the projection of altruism and the individual(istic) satisfaction generated by the engagement ‘for a greater good’. More prosaically, it can also consist of building one’s public image (though public speeches and media appearances for example) or one’s professional résumé. The existing tension between the roles and functions that the same cohort of actors seems to express, illustrates more than a binary or artificial opposition between engagement in associations and in grassroots movements. It displays an illusory distance towards “paid” forms of engagement in a sector that has fallen in an “implementation trap” vis à vis donor agendas (AbiYaghi, Yammine, and Jagannathsingh, 2019) through the denigration of professions in the associative sector.

This tension could result from the increased demonization of the associative sector in the mainstream public discourse, with increased accusations of corruption by their donors, state authorities, and the general public. It could also result from the perception that professional activists may “move from one cause to another, bringing their specialized skills with them—for a price” (Jasper et.al., in Della Porta and Diani, 2015, p.8). Indeed, aid cooperation and international partnerships for development, in the forms of ODA, funding to the associative sector, or charity initiatives to the most disenfranchised, can be considered as a vector of reproduction of the status quo – of the political system and societal norms, social stratification, for example. This aid economy fails to address the root and structural causes of the mere challenges they seek to address, often relying on cosmetic participatory and consultative processes, in which the associative sector and “paid” activists engage in. However, contentious dynamics of mutual demonisation (or fascination), and the adoption of containing rhetoric (notably used by the state, establishment political parties, mainstream media, etc.), directly contributes to the reproduction of the mere system(s) that both paid and non-paid activists seek to challenge, and feeds in the mainstream demonisation of both groups of actors: grassroots activists considered as non-organised, prone to violence, and lacking leadership on the one hand, and associations labelled as following external agendas, and engaging in the misuse and squandering of public funds on the other hand.

Hence, binary narratives and practices within the activist and academic circles appear non-heuristic and counterproductive as both, “professional” and “grassroots” forms of engagement, fulfill distinct and complementary social functions.

This complementarity, however, stumbles on the limits of multi-positionality of some actors that navigate at the same time grassroot activist positionalities and expertise or consulting positions with state authorities, or international institutions, which illustrates the limits of their contentious role (going against the saying of biting the hand that feeds), while their expertise positionality appears to capitalise on their activist profile. It is noteworthy to highlight here that all types of “grassroots activism” do not appear to be born equal, with some types of more ideological and political commitments still being marginalised even within activist circles.

Conclusion

The genealogy of movements allows to draw light on the processes they instigated and that led up to the most recent protest cycle in the country, that is the October 2019 protests. To have a better understanding of these social mobilisations, their dynamics, and limits, we relied on a framework revolving around three strategies used: persuasion, coercion, and retribution. These were employed to analyse the interactions among these actors themselves, as well as the dynamics and interactions with other actors and the state. By understanding these, we can grasp the strategic choices actors make and how this shapes their actions.

Within the Lebanese consociational and power sharing system, taking a longitudinal look at social mobilisations and movements over time, brings to light the continuity and evolution of demands. These cycles may appear to fulfill the role of outlet for grievances, rather than challenging the social and political structures in the country. In a context of increasingly shrinking civic space, due to structural factors and practices (by the state, establishment parties, and media, international donors and community etc), it is noteworthy that it is not merely the system that hinders mobilisations, but also, oftentimes, strategic choices adopted by the mobilising actors themselves, who end up contributing to the shrinking space and to reproducing the status quo, while mobilising against it. In this longitudinal perspective, and rather than drawing conclusions after each protest cycle, we argue for the examination of mobilisations on the micro level, and how they accumulate in a long temporality and feed into successive waves of movements, rather than assess them in terms of successes or failures.

This paper was originally published by the Arab NGO Network for Development, part of the Civic Space Watch, and is available on this link alongside reports from 10 other Arab countries.

Bibliography:

AbiYaghi, Marie-Noëlle. “Civil Mobilization and Peace in Lebanon”, in Picard, Elisabeth and Ramsbotham, Alexander (eds). Reconciliation, reform and resilience. Positive Peace for Lebanon, Issue 24. London: Accord Publications. July 2012.

AbiYaghi, Marie-Noëlle. L’altermondialisme au Liban : un militantisme de passage. Logiques d’engagement et reconfiguration de l’espace militant (de gauche) au Liban, Doctorat de science politique. Paris: Université de Paris1-La Sorbonne. 2013.

AbiYaghi, Marie-Noëlle, Catusse, Myriam, and Younes, Miriam. “From isqat an-nizam at-ta’ifi to the Garbage Crisis Movement: Political Identities and Antisectarian Movements.” In di Peri, Rosita and Meier, Daniel (eds.). Lebanon facing the Arab Uprisings. Constraints and Adaptation. London: Palgrave. 2017.

AbiYaghi, Marie-Noëlle, Yammine, Léa, and Jagarnathsingh, Amreesha. Civil Society in Lebanon: the Implementation Trap. Beirut: Lebanon Support, 2019. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/civil-society-lebanon-implementati...

Duyvendak, Jan Willem and Jasper, Jim (eds). Players and Arenas, The Interactive Dynamics of Protest. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 2015.

Favier, Agnès. Logiques de l’engagement et modes de contestation au Liban. Genèse et éclatement d’une génération de militants intellectuels (1958-1975), thèse de doctorat en science politique. Marseille: Aix-Marseille III, Université Paul-Cézanne. 2004.

Jasper, Jim et. al. “Strategy.” In Della Porta, Donatella and Diani, Mario (eds). The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2015.

Karam, Karam. Le Mouvement Civil Au Liban, Revendications, Protestations et Mobilisations Associatives Dans L’Après-Guerre. France: Editions Karthala - Iremam. 2006.

McAdam, Doug, Tarrow, Sidney, & Tilly, Charles. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2001.

Mitri, Dalya. “From Public Space to Office Space: the professionalization/NGOization of the feminist movement associations in Lebanon and its impact on mobilization and achieving social change.” In Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi, Bassem Chit, and Léa Yammine (eds). “Revisiting Inequalities in Lebanon, The case of the “Syrian refugee crisis” and gender dynamics,” The Civil Society Review, Issue 1. Beirut: Lebanon Support. 2015.

Moghniye, Lamia. Local expertise and global packages of aid: The transformative role of volunteerism and locally engaged expertise of aid during the 2006 July war in Lebanon. Beirut: Lebanon Support. 2015, a. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/local-expertise-and-global-package...

Moghniye, Lamia. Local forms of relief during the July war in 2006 and international humanitarian interventions: Implications on community preparedness for war and conflict. Beirut: Lebanon Support. 2015, b. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/local-forms-relief-during-july-war...

Lebanon Support. “Collective Action digest, 22 October 2019.” Civil Society knowledge Centre. https://civilsociety-centre.org/digest/collective-action-digest-22-octob... (Last accessed on 8 April 2020).

Lebanon Support. “Crackdown on Social Media by Lebanese Authorities. (Infographic)” Civil Society knowledge Centre. https://civilsociety-centre.org/content/crackdown-social-media-lebanese-... (Last accessed on 8 April 2020).

Lebanon Support. “Women’s Movements in Lebanon.” Civil Society knowledge Centre. https://civilsociety-centre.org/gen/women-movements-timeline/4938#event-.... (Last accessed on 27 March 2020).

Lebanon Support. “Map of Collective Actions in Lebanon” Civil Society knowledge Centre. https://civilsociety-centre.org/cap/collective_action. (Last accessed on 8 March 2020).

Lebanon Support. “Map of Collective Actions in Lebanon” Civil Society knowledge Centre. https://civilsociety-centre.org/cap/collective_action/charts. (Last accessed on 8 March 2020).

Tavana, Daniel and Parreira, Christiana. Lebanon’s 2018 Election: New Measures And The Resilience Of The Status Quo. Beirut: Lebanon Support. 2019.

- 1. For more on the legal and political systems governing the work of CSOs and civic space in Lebanon, please read “Civil Society in Lebanon: The Implementation Trap” https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/civil-society-lebanon-implementati...

- 2. For more on this read: https://civilsociety-centre.org/gen/women-movements-timeline/4938#event-...

- 3. This period between 2006 and 2007 consecrated the role of local and grassroots organising, within groups such as Samidoun, outside of traditional structures of aid and relief, in ensuring the country’s preparedness and response to crises (Lamia Moghniye, 2015, a). These responses and actions built on previous experiences and routinised data sharing and information coordination in order to enable a more efficient provision of aid to affected communities (Lamia Moghniye, 2015, b).

- 4. Accessible on: https://civilsociety-centre.org/cap/collective_action

- 5. Accessible on: https://civilsociety-centre.org/cap/collective_action/charts

- 6. Read more in Lebanon Support’s Collective Action digest, 22 October 2019: https://civilsociety-centre.org/digest/collective-action-digest-22-octob...

- 7. Jasper observes three basic families of strategic means: paying others to do what you want, persuading them to, and coercing them to.

- 8. For more, see Human Rights Watch website on the protests documenting violations: https://www.hrw.org/blog-feed/lebanon-protests

- 9. See the work of Gherbal Initiative, and https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/09/27/lebanon-access-information-law-stalled

Marie-Noëlle Abi Yaghi specialises in the sociology of contentious politics in contemporary Lebanon, with a focus on transformation of commitment and logics of disengagement, as well as gendered dynamics within social movements. She also focuses on (re)production processes and forms of social control, order, and discipline. AbiYaghi is currently the co-director of the CeSSRA and a lecturer at the Institute of Political Science at the Saint-Joseph University, Beirut.

Marie-Noëlle holds a PhD in Political Science from the Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, France.

E-mail: mabiyaghi@socialsciences-centre.org

Twitter: https://twitter.com/mnabiyaghi

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8558-6722

Léa Yammine is a creative and researcher. Her main research areas and work revolve around on communication, visualisations, social justice, civil society, and gender. She is currently the co-director of the CeSSRA.

Léa holds a BA in Graphic Design from the American University of Beirut, and an MA in Culture, Creativity & Entrepreneurship from the University of Leeds, UK.

Email: lea@socialsciences-centre.org

Twitter: https://twitter.com/lea_yam