Can A National Unified Registry in Lebanon Constitute A Step Towards Universal Social Protection? A Comprehensive Technical Report

This report examines the feasibility of creating a National Unified Registry (NUR) for Lebanon as a cornerstone of any effective social protection scheme. A robust registry streamlines outreach, intake, beneficiary registration, and eligibility validation, ensuring better resource allocation—especially critical during crises when needs intensify, resources diminish, and social protection providers multiply.

To cite this paper: Nizar Hariri, Iskandar Boustany,"Can A National Unified Registry in Lebanon Constitute A Step Towards Universal Social Protection? A Comprehensive Technical Report", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2025-04-01 00:00:00. doi:

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/national-unified-registry-lebanon-step-towards-universal-social-protection

Table of Contents

Section 1: A Landscape of Scattered Schemes and Systems

2.1. A Holistic Approach to the Public Sector Amidst the Rise of the Digital State

2.2. The Potential of Interoperability and the Spillover Effect

2.3. A Revised Setting to Meet the Requirements of Data Management

2.4. The Prominent Risks of Ethical Challenges

2.5. Technological Challenges: from the Software to the Hardware of Data Privacy

2.6 Political Control, Institutional Mandates, and Communitarian Considerations

3.1. Finding the Balance between Full-scale Reform and an Incremental Approach

3.2. The Delicate Task of Designing a National Unified Registry

ABBREVIATIONS

CAS Central Administration of Statistics

CSC Civil Servants Cooperative

CeSSRA The Center for Social Sciences Research & Action

ESSNP Emergency Social Safety Net Program

GIS Geographic Information System

ID Identity Document

ILO International Labour Organization

MoF Ministry of Finance

MoPH Ministry of Public Health

MoSA Ministry of Social Affairs

NPTP National Poverty Targeting Program

NSPS National Social Protection Strategy

NSSF National Social Security Fund

NUR National Unified Registry

PCM Presidency of the Council of Ministers

SP Social Protection

SPIMS Social Protection Information Management System

UNICEF United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This technical research was based on an extensive literature review of publicly available documentation and on insights collected from key informant interviews conducted with representatives of stakeholder institutions. The authors and Cessra are grateful for the generosity in sharing their expertise and insights, of the following experts (in alphabetical order):

- Marie-Louise Abou Jaoudeh, Project Manager, NPTP Unit at the PCM;

- Chawki Abou Nassif, Financial Director and Head of the Bureau at the NSSF;

- Khalil Dagher, Social Policy / Social Assistance Specialist at UNICEF LCO;

- Gerry Fitzpatrick, Team Leader at DAI;

- Stephen Kidd, Senior Social Policy Specialist at Development Pathways;

- Ahmet Fatih Ortakaya, Senior Social Protection Specialist at the WB;

- Raymond Tarabay, Minister Advisor on Social Protection at MoSA.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Lebanon's social protection system has historically been inadequate, failing to provide essential safeguards for its population. Even before the financial collapse of 2019, the system faced significant challenges due to limited financial resources and policy inertia. The subsequent crisis further distorted the landscape, shifting from contributory schemes—primarily benefiting public sector employees—to non-contributory social assistance and an unsustainable dependence on donor funding.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the government launched the National Social Solidarity Program, which offered direct cash payments to households affected by overlapping crises. Eligibility for these payments was determined based on categorical criteria that evolved during implementation (International Labor Organization, 2021). Between 2021 and 2023, efforts were made to expand social assistance coverage through key initiatives, including the World Bank-funded, poverty-targeted Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN), and the expansion of the National Poverty Targeting Program (NPTP), financed via a World Bank loan. Additionally, Lebanon introduced its first social grants program, the National Disability Allowance, funded by the EU and supported by UNICEF and the ILO.

Despite these efforts, the approach remains largely ad hoc and exclusionary, falling short of a rights-based framework. However, steps toward reform offer some promise. Notably, the government enacted legislation establishing a comprehensive pension system for private-sector workers, fundamentally transforming the governance of existing social security schemes. This development, along with the adoption of the National Social Protection Strategy (NSPS), represents a critical juncture in advancing toward a more inclusive and universal social protection system. The NSPS underscores the importance of creating a "unified single registry" as a strategic priority.

Effective social protection reform hinges on the establishment of unified and consolidated registries. Without this foundation, inefficiencies, resource misallocation, and inadequate welfare coverage persist. This report examines the feasibility of creating a National Unified Registry (NUR) for Lebanon as a cornerstone of any effective social protection scheme. A robust registry streamlines outreach, intake, beneficiary registration, and eligibility validation, ensuring better resource allocation—especially critical during crises when needs intensify, resources diminish, and social protection providers multiply.

Before delving into methods of achieving registry integration, interoperability, or unification, it is essential to clarify the distinctions between national, social, and beneficiary registries. Although these terms are often used interchangeably, they serve distinct purposes, have different functionalities, and carry unique political implications. This report emphasizes the importance of aligning database design with the overarching social protection paradigm. A unified registry can either be a milestone toward an inclusive, universal system or a mechanism for screening targeted assistance policies. It is vital to ensure that the creation of a unified registry is part of a broader, sustainable strategy that strengthens—rather than undermines—Lebanon’s fragile social protection system.

Methodology

This report was developed through a comparative review of existing literature to identify lessons from neighboring contexts and countries. The review aimed to highlight key challenges and pitfalls to address early in the design and implementation of a unified registry. Additionally, seven in-depth interviews were conducted with key informants from the public sector and experts from international agencies, providing insights into social protection issues both in Lebanon and globally.

While this report addresses a critical gap in Lebanon's social protection discourse, it does not claim to offer a technical assessment of current information management systems or a comprehensive legal review of the frameworks governing social protection data. Instead, it seeks to stimulate an evidence-based debate by outlining key challenges and issues surrounding the development of a unified registry, thereby paving the way for further research.

Key findings

▪ Systemic blindness in crisis response: Lebanon’s social protection system has demonstrated significant weaknesses in responding to crises, particularly since the onset of the war in Syria in 2011. The inability to swiftly and accurately target individuals in need has resulted in ineffective delivery of benefits and services. Ad-hoc registries, such as the National Poverty Targeting Program (NPTP) and the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN), were designed without a cohesive strategy, facing challenges in targeting and verification. Consequently, the system has struggled to provide clear insights into the most effective mechanisms for addressing external shocks.

▪ Fragmented Social Protection Programs: Lebanon’s social protection landscape is fragmented, with over 145 identifiable programs and services documented in official records and the national budget. This fragmentation is particularly evident in social insurance schemes, which are managed by separate entities. The absence of aggregated enrollment data underscores the need for a unified registry to consolidate and streamline these programs.

▪ Political risks associated with data scarcity: The lack of comprehensive data exacerbates structural deficiencies and fragmentation, introducing political risks such as policy misuse. Political actors’ tolerance of data scarcity undermines the design and implementation of effective social protection measures, perpetuating inefficiencies and inequities in service delivery.

▪ Digital transformation and governance risks: The increasing reliance on digital technologies raises concerns about democratic governance. While these tools can enhance efficiency, they also pose risks to privacy, justice, and equity. Lebanon’s current surveillance practices, characterized by cybersecurity vulnerabilities and unauthorized data collection, present significant challenges to citizen privacy and governance.

▪ Legal and ethical challenges: The unification of registries must navigate complex legal, institutional, and technical requirements. Balancing ethical, moral, and professional obligations — such as maintaining confidentiality while adhering to legal mandates — will be critical for ensuring fairness and effectiveness in the unified registry.

▪ Importance of data management: Effective management and utilization of state-owned data has become a critical component of public intervention, comparable to the management of financial and human resources. The provision of high-quality public services increasingly depends on the efficient handling and application of data. This underscores the urgent need for a unified registry that supports these efforts, ensuring streamlined access to and use of data for decision-making and service delivery.

▪ Inclusion of informal workers: Incorporating informal workers into the National Unified Registry requires upstream efforts to categorize diverse employment types. Approaches that exclude informal sectors risk inequity, underscoring the need for a balanced strategy to achieve inclusivity while maintaining fairness.

▪ Comprehensive dataset for targeting and revenue enhancement: A unified registry that connects with other registries using unique identifiers can generate detailed datasets, including those for partially or seasonally employed individuals and informal sector workers. This data is critical for precise targeting, addressing tax evasion, and enhancing employer contributions, ultimately improving the funding and coverage of the social protection system.

▪ Optimizing costs and revenues: A unified registry enables social protection institutions to uniquely identify each resident, track various forms of reimbursement, coverage, and assistance, and reduce duplication of efforts. This ensures continuity between contributory and non-contributory schemes while safeguarding public funds. Private institutions and international organizations can also leverage this unique identifier to report beneficiary data, enhancing the efficiency and coordination of the social protection system.

▪ Challenges in beneficiary selection: Establishing fair and transparent outreach methods for selecting beneficiaries presents a significant challenge for both state-centric programs and humanitarian organizations. The debate over “eligibility” often conceals a deeper “legibility” issue, where ambiguity and inconsistency in definitions and categorizations can lead to manipulation or misrepresentation of data. Addressing this issue is essential for ensuring the success of a unified registry, as it will promote accuracy, fairness, and trust in the system.

▪ Addressing bureaucratic definitions: Terms such as “vulnerable,” “precarious,” and “poor” are often subject to negotiation between service providers and recipients. This dynamic creates a “moral economy of lying,” where recipients adapt to fluctuating and arbitrary definitions to meet eligibility criteria. Preparatory efforts to establish a National Unified Registry (NUR) must thoroughly address these bureaucratic definitions, classifications, and eligibility criteria in advance. Doing so will improve the resource allocation of non-contributory programs and ensure better integration with mandatory and contributory schemes.

Challenges and recommendations

▪ The security, confidentiality, and privacy of data must be guaranteed through the use of secure technologies. Lebanon’s current surveillance system has been characterized by widespread violations of personal privacy and significant cybersecurity vulnerabilities, posing serious risks to citizens’ data security. Concerns over national security or perceived threats often result in predatory actions by police, paramilitary groups, and militias, many of whom operate beyond the boundaries of legal authority. Additionally, various state actors are involved in extensive digital surveillance, exacerbating these risks further. To mitigate these challenges, institutions and authorities responsible for handling sensitive data must implement robust cybersecurity measures. Moreover, they should establish comprehensive legal frameworks to regulate surveillance activities, ensuring that citizens’ privacy is protected against unauthorized access and malicious third parties.

▪ Further research is needed to understand the political role and instrumentalization of data in Lebanon. Such research will shed light on how data is constructed politically, hereby unveiling its function in upholding existing power structures. It should investigate the mechanisms through which data influences political decision-making and governance, exploring how it may either reinforce or challenge dominant narratives.

▪ A tailored approach to data management should address legal, ethical, and practical challenges specific to Lebanon. This approach includes the development of legal frameworks that build public trust and promote ethical data practices. Public resistance to data management reforms should be tackled through transparency, informed consent, and participatory processes. Furthermore, the design of the data management system should promote collaboration between ministerial bodies and third-party public entities, ensuring the effective integration of data sources while upholding privacy and ethical standards.

▪ A holistic approach requires simultaneous reforms across the public sector. Reform must involve simultaneous changes across various sectors of government. This includes establishing a labor market information system, reforming tax administration, and implementing universal social policies. Reforms must also address critical issues such as data security and protection, as well as scrutinizing the operations of the judiciary and military/security apparatus. These comprehensive reforms are essential for creating an environment conducive to effective data governance and integration, ultimately enabling the successful development of a robust National Unified Registry (NUR).

▪ Gradual integration might be the most practical way forward, aiming to establish a unified registry through a step-by-step process rather than attempting to break down the entire reform project into smaller, isolated tasks. Political interference in one area often causes blockages in others, potentially stalling the entire modernization effort. By adopting a gradual integration strategy, Lebanon can mitigate these risks, ensuring continuous progress toward a unified information management system that effectively supports social protection.

▪ Leveraging Existing Legal Frameworks. Existing legal frameworks, such as the Unified Identification Number Law and the E-Transactions and Personal Data Law, should be effectively leveraged in the design of the National Unified Registry (NUR). The Unified Identification Number Law assigns the responsibility for issuing and managing identification numbers to the Directorate-General of Civil Status, which must be integrated into the NUR’s design. Furthermore, laws such as the Consumer Protection Law and the Lebanese Government Interoperability Framework should guide the development of a comprehensive and legally sound registry that aligns with existing legal structures.

▪ The trap of over-reliance on social registries should be avoided. It is crucial to avoid over-relying on social registries, as this can lead to narrowly focused and ineffective systems. While building upon existing efforts, the National Unified Registry (NUR) should not be restricted to serving as just another targeted social registry. Instead, it must evolve into a comprehensive system that encompasses all social protection programs. Targeted registries often fail due to outdated assumptions and a lack of continuous updates, resulting in inefficiencies and inequities. The NUR should be designed to be dynamic and adaptable, capable of responding to evolving household structures and changing socioeconomic conditions.

▪ Drawing Lessons from International Experiences. International experiences highlight the limitations of targeted registries that rely on static assumptions, which often lead to their failure due to outdated data collection methods. Such registries struggle to evolve into comprehensive systems, like the National Unified Registry (NUR), that can effectively manage diverse and dynamic social protection needs. The NUR must be designed as a flexible, adaptable system that is regularly updated to account for changes in household structures and socioeconomic conditions. By drawing from international lessons, Lebanon can avoid these common pitfalls and create a more effective, resilient data management framework.

▪ Strengthening Institutional Governance for Data Management. Establishing a robust foundation for data management and integration in Lebanon necessitates a comprehensive overhaul of institutional governance. The digital strategy developed by the Office of the Minister of State for Administrative Reform (OMSAR) provides an excellent starting point for initiating a national conversation on digital governance. This strategy should clearly define roles and responsibilities while creating a governance framework that fosters effective data management and integration across various sectors. This will ensure that Lebanon can optimize its digital resources, streamline public service delivery, and create a cohesive system for managing critical data across government institutions.

▪ Expanding Governance to Include NGOs. Effective governance for data management should extend beyond the public sector to involve non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which play a vital role in providing social protection services in Lebanon. Integrating efforts across both public and NGO sectors is crucial for addressing emerging needs and responding to external shocks in a timely and accurate manner. To achieve this, a coordinated governance framework is essential—one that facilitates data sharing and collaboration between state and non-state actors. Such integration will enable a more responsive, efficient, and inclusive system for managing social protection programs, particularly during crises.

▪ Building Trust between institutions through Transparent Data Governance. Establishing trust between institutions is fundamental to a successful data management model. This process requires the creation of a transparent and comprehensive framework for data sharing and access, where roles and responsibilities are clearly defined. Ensuring transparency and accountability in data governance practices is vital for fostering institutional trust. When data management practices are open and well-regulated, institutions can work together more effectively, with confidence that data will be handled responsibly and ethically.

▪ Establishing and enforcing a framework for data governance is critical. This framework should include guidelines for data structure, accessibility, transparency, security, and privacy. Lebanon has a history of digital transformation strategies, which should be continuously updated and refined to reflect new trends and challenges. A robust data governance framework will support the development and maintenance of the NUR.

▪ Hosting all social data within the country is a prerequisite for ensuring data security. Many ministries currently store their data on external clouds, which poses security risks. Utilizing local data centers, such as Ogero, can enhance data security by ensuring that state-owned and state-managed databases are housed within a secure national infrastructure.

▪ Data management should be professionalized in the public sector. The function of data management is as important as financial and human resource management in modern public operations. This requires establishing data management units across line ministries and professionalizing data management positions in the public sector. Developing a clear competency framework and building institutional capacity will enable the state to manage and adapt to larger scales of data generation, ensuring readiness for continuous changes and new trends.

INTRODUCTION

Catching Momentum: Why Having a Unified Registry is Unavoidable in Today’s Context?

Four years into successive crises (including a financial and social crisis, the Covid pandemic, the Beirut port blast, a political deadlock, and more recently, a devastating war), Lebanon finds itself at a critical juncture. The launch of the first National Social Protection Strategy (NSPS) in 2024 is a promising development, earning praise from international agencies such as the ILO and UNICEF as “a significant milestone in Lebanon’s ongoing recovery efforts and a first step towards comprehensive social reform” (ILO, 2024 a, p.1). However, this optimism risks being swiftly undermined if the government succumbs to policy inertia and continues its historical tendency to outsource responsibilities and delegate functions to third parties.

Lebanon’s social protection system was already inadequate and ineffective in providing basic safeguards for the population (CAS & ILO, 2019) and preventing the severe consequences of economic and social turmoil. Furthermore, the crisis has introduced a set of structural risks and challenges that could further erode the state’s role as a key provider of social protection services (Hariri, 2023). Indeed, the lack of financial resources, compounded by policy inertia, has created a significant distortion in social protection services. This is evident in the gradual shift from contributory schemes, which are already skewed in favor of public sector employees (Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, 2021), to non-contributory social assistance and a growing reliance on donor financing. As a result, the current state-managed social protection model seems to prioritize a humanitarian, exclusionary approach at the expense of a rights-based framework. Moreover, state-centric social protection institutions appear to be losing ground to private sector entities and humanitarian or sectarian groups, while public coverage is shrinking, leaving the “missing middle” to fend for itself (Mezher, 2021).

In parallel with the promising NSPS, the Lebanese government enacted new legislation at the end of 2023 to establish a comprehensive pension system for private sector workers (L'Orient-Le Jour, 2023). At least in theory, this legislation represents a fundamental shift in the governance of existing social security schemes, presenting a pivotal opportunity to move toward a more inclusive and universal social protection system. However, implementing social protection reforms that introduce new registries without first establishing unified and consolidated registries, or at least defining a clear vision for the structure and design of the unified registry, risks contributing to a cycle of inefficiency, resource misallocation, and persistent inadequacy in meeting Lebanon’s social welfare needs. Therefore, despite these promising first steps, several critical questions remain: How can the state design and implement effective, evidence-based social protection policies without a reliable and comprehensive data source? (ILO 2024, b). How does the absence of a comprehensive social registry impede the government’s ability to accurately identify and target beneficiaries for social protection programs? How can the state promote universal and inclusive programs when public and private institutions operate in silos, using incompatible information systems and registries?

The complexity of these questions stems from a lack of comprehensive understanding regarding the development, utilization, and maintenance of databases and information systems across public entities. In response, this report focuses on examining the potential benefits of transitioning from fragmented, siloed information systems to more integrated and interoperable frameworks, emphasizing equity and inclusivity in the distribution of social welfare.

This report also advocates for the establishment of a National Unified Registry (NUR) for Lebanon. The development of such a registry is often viewed as the first step in the delivery chain of any social protection scheme (Lindert et al., 2020). A well-designed registry would facilitate outreach, intake, beneficiary registration, and eligibility validation for welfare programs. Accurate and detailed data on residents becomes particularly critical during crisis and post-crisis periods when needs are heightened, resources are limited, and the number of social protection providers increases.

The methodology of this report includes a comprehensive literature review and a comparative approach to draw lessons from neighboring countries, identifying key risks that should be addressed early in the design and implementation of a unified registry. It also features seven in-depth interviews with key informants from the public sector and international experts working in Lebanon and comparable contexts. The report argues that developing a unified registry is a prerequisite for creating a functional and equitable national social protection system, as it enables the efficient flow and management of information across various programs and sectors, such as education, health, civil records, and fiscal records A unified information system or registry would enhance numerous functions, including: enabling the government to identify and target intended populations; profiling needs; tailoring benefits and services; monitoring beneficiaries; addressing coverage gaps and redundancies; improving data accuracy; reducing costs; and streamlining administrative procedures.

This report further highlights the significant strides made by the Lebanese government and public entities toward improving their information systems and beneficiary lists. Notable initiatives include efforts led by the Presidency of the Council of Ministers to enhance inter-ministerial coordination. Policymakers increasingly recognize the importance of information sharing, database integration, and system consolidation. However, before discussing how such integration and interoperability can be achieved, it is crucial to clarify what exactly is being unified or integrated. Whether referring to national, social, or beneficiary registries—terms often used interchangeably but representing distinct concepts—it is essential to first assess their purpose, functionality, and political implications. As powerful tools of public policy, databases are inherently shaped by ideological and political considerations. Consequently, the social protection framework guiding their design and development warrants careful examination. Is the unified registry envisioned as a monitoring mechanism, a step toward an inclusive and universal social protection system, or a screening instrument for targeted social assistance programs? Is it an isolated initiative or a component of conditional social assistance programs that risk undermining the universality of Lebanon’s social protection system (Scala, 2022)? Thus, while advocating for the establishment of the NUR, this report critically examines a range of risks and contentious issues, including data scarcity, institutional fragmentation, privacy concerns, reliance on donor funding, and other obstacles that have impeded the implementation of national registries in various countries. These challenges are particularly pronounced when governments initiate targeted registries under the premise of future expansion, only to create fragmented, low-coverage systems reliant on outdated or inadequately collected data (Kidd, Athias, & Mohamud, 2021).

Section 1: A Landscape of Scattered Schemes and Systems

The Lebanese crisis has exposed two major structural shortcomings in the country’s formal social protection framework. First, it was never aligned with a lifecycle approach. As a result, many elderly individuals, already facing heightened vulnerabilities, were pushed below the poverty line, losing their lifetime savings and access to essential social protection services amidst the country’s economic and monetary collapse (Abi Chahine, 2022). Second, it did not account for external shocks that seem to be recurrent in Lebanon. Over the past few years, the country has endured a series of large-scale external shocks, including the Beirut Port blast, COVID-19, and the Israeli war in Gaza and in Lebanon. These events have had profound direct and indirect impacts on society, while the government struggled to respond proactively, implement timely mitigation measures, or formulate effective policies to address the rapid and widespread fallout. [1]

The root causes of these shortcomings can largely be attributed to the absence of a policy-driven approach to social protection, coupled with a lack of planning, preparedness, sustainable financing, and, undoubtedly, political will. However, the multilayered crises that Lebanon has faced since the onset of the war in Syria war in 2011 have exposed an even more alarming reality: the system was simply blind. The blindness was twofold: (i) the system could not swiftly and accurately identify people in need of urgent intervention and consequently provide tailored benefits and services. Even poverty-targeting social assistance programs were designed ad-hoc (such as the NPTP and the ESSN) and faced multiple challenges in targeting and verification; and (ii) The system was unable to offer clear insights into the most effective delivery mechanisms and measures to address external shocks because existing targeted registries were, by design, created to respond to specific, predefined challenges.

On a more positive note, the approval of the NSPS represents a significant milestone toward comprehensive and inclusive reform. The strategy explicitly highlights the strategic necessity of establishing a unified registry. However, it does not provide a concrete, actionable framework for the effective development of a unified or integrated delivery system. Furthermore, it fails to specify the exact type of registry required to address systemic deficiencies in oversight and the broader implications of such gaps on social policies within the envisioned national social protection framework.

In practice, the success of any social protection scheme in precisely identifying beneficiaries, ensuring seamless enrollment, delivering adequate support, adapting to evolving needs, and maintaining effective monitoring depends on the implementation of a real-time data system. This system must also facilitate information exchange through the integration of key functions along the social protection delivery chain. Interoperability with other government systems is essential to achieve economies of scope and scale (Chirchir & Barca, 2020).

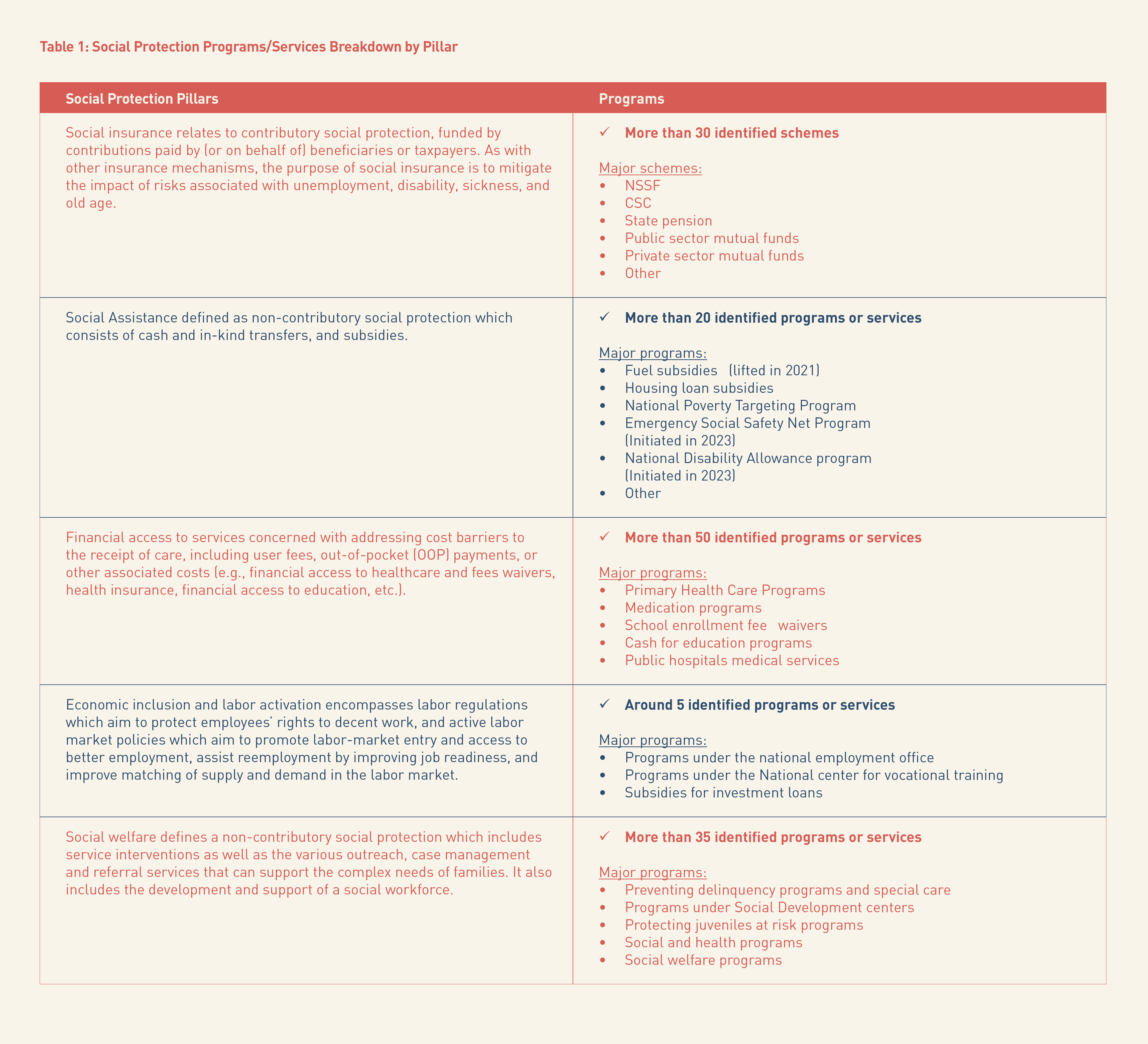

Despite some shifts in Lebanon’s social protection landscape following the crisis, it remains characterized by fragmented schemes and systems. A rapid mapping of state-financed and state-managed schemes (Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, 2021; see Appendix 2) reveals the following:

▪ There are over 145 identifiable social protection programs and services reflected in the budget and official documentation. If an official and comprehensive mapping of social protection services were conducted, this number would likely increase significantly. The exact number of registries or databases associated with these programs remains unknown. However, in the absence of integration plans, it can be reasonably inferred that the number of individual beneficiary databases corresponds to the number of identified programs.

▪ Although the lead on the social protection portfolio seems to oscillate between the Presidency of the Council of Ministers and the Ministry of Social Affairs, no single state entity can claim having a full grasp of all operational social protection programs and services or a deep understanding of their coverage, benefits, and mechanisms.

▪ Social insurance schemes are among the most fragmented, as each is managed independently by a different entity. Moreover, no official aggregate data on total enrollment is compiled or published. This lack of coordination systematically undermines key functions such as targeting, cross-checking, and validation, creating significant vulnerabilities within the system. These include widespread injustice, such as high levels of uncovered individuals and the exclusion of large segments of the population, as well as opportunities for system abuse (including redundancy, rent seeking, and clientelism, etc.).

▪ While certain state entities, such as the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Ministry of Public Health, may manage or operate multiple programs simultaneously, this does not necessarily imply full integration of services. As a result, the system lacks the accuracy and integrity needed to effectively prevent errors and fraud.

▪ The proliferation of similar schemes imposes a substantial administrative burden on registry management, particularly during crises, when the state faces an irreversible loss of human capacity and is constrained by limited fiscal resources. Establishing a unified national registry would significantly alleviate the operational strain on numerous public administrations while reducing the operational and transactional costs associated with managing information systems. Additionally, donor-funded programs would benefit from more targeted and effective logical frameworks, especially given the country’s short-term (yet, recurring) reliance on international social assistance.

▪ Data scarcity not only contributes to structural deficiencies and fragmentation within the social protection landscape but also presents a political risk that Lebanese politicians seem willing to accept, despite the potential for increased opacity and misuse of public policies. Given the context outlined above, the critical question is: Can Lebanon overcome such a multitude of political and governance challenges?

Table 1: Breakdown of Social Protection Programs/Services by Pillar

Remark: Most of the information included in this table was sourced from the references stated below. Some programs were discontinued, such as the fuel subsidy that was lifted in August 2021, while a few others remain, such as the wheat subsidy financed by a World Bank loan that is about to come to term and a subsidy on the provision of medication for chronic diseases. Other programs, originally financed by the state budget, such as pension programs, social welfare programs, and other programs handled by line ministries, were severely reduced in scale and size due to the fiscal and monetary crisis. A small number of social assistance programs were initiated, such as the World Bank-financed, poverty-targeted Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN), in addition to the design and roll-out of Lebanon's first-ever social grants program, the National Disability Allowance, which is funded by the EU and jointly supported by UNICEF and ILO.

References: Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan, 2021, World Bank Group, 2023, UNICEF, 2023.

Section 2: The Urge to Re-design: Can Lebanon Meet the Requirements for Transitioning to a Unified Registry?

The consolidation and unification of public data, as well as the mainstreaming of unified registries in public management, are ambitious undertakings that have the potential to “revolutionize” administrative practices and standards (Tomlinson, 2019). These efforts also pose a significant challenge to the political elite’s control over the system, while raising important questions about social justice and public governance (Raul, 2002). Governments, state-centric institutions, and local authorities at various levels are increasingly adopting digital technologies, information and communication technologies (ICTs), and data-driven approaches in their operations and services. However, the rise of a digital state governance framework brings concerns about the transformation of justice in the digital realm, the potential for abuse of private data, and the risks posed to individual citizens and independent actors within civil society by an overarching digital system (Zuboff, 2023).

Before proceeding, several key questions must be addressed: Which legitimate institutions should be granted privileged access to unified public records, and how can the unwarranted invasion of private life be prevented or sanctioned? What are the prerequisites for better governance of public information that preserves and protects fundamental rights? How can a balance be achieved between open access to government records and the safeguarding of personal information?

Given the current fragmentation of Lebanon’s social protection landscape, the unification of national registries must meet essential legal, institutional, and technical requirements (Figure 1). More importantly, it must reconcile conflicting sets of moral and professional values, such as the medical duty to maintain confidentiality versus the legal obligation to report abuse or violence to the state, judicial authorities, or third parties. This section provides a brief overview of the major prerequisites for establishing a unified or integrated registry, while primarily focusing on the conflicting considerations—such as the right to privacy, professional secrecy, and ethics—that may pose challenges to the design and implementation of these systems.

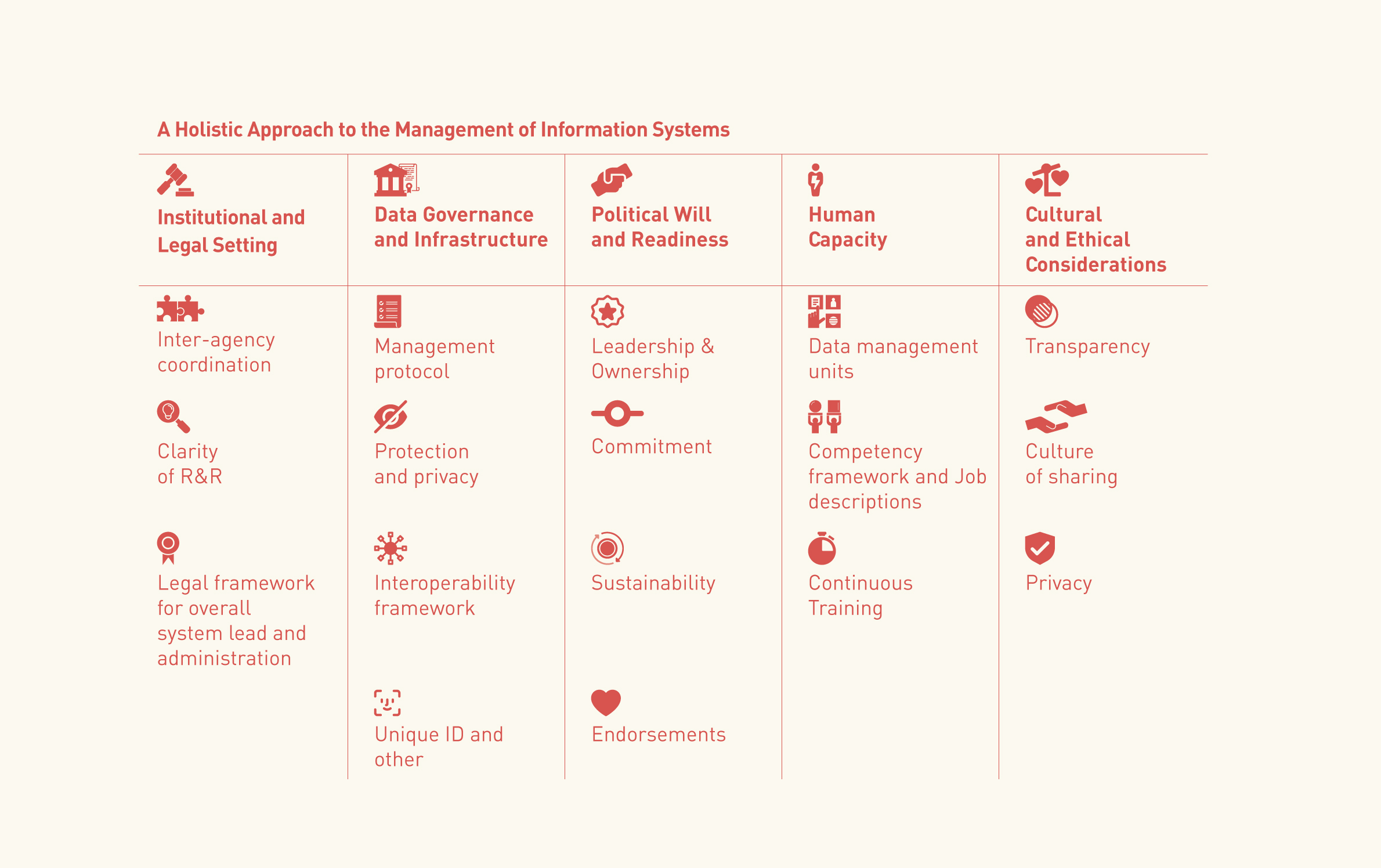

Figure 1 Key Requirements for Integrating Social Protection Information Systems

Reference: George & Leite, Integrated Social Information Systems and Social Registries, 2019, adapted.

The management of information and data systems is increasingly regarded as being on par with financial and human resources management in the context of public interventions. This shift is due to the growing reliance on the effective management and use of state-owned data to provide quality services. Like the other two functions, this inherently necessitates the establishment of a comprehensive and well-structured data governance system. Such a system should define and enforce policies, procedures, and standards to ensure the effective management, use, and protection of data, including aspects like protection and security, regulatory compliance, interoperability, quality and accuracy, ownership, and access protocols. Above all, it fosters a cultural shift within government agencies.

The literature clearly outlines the requirements for creating a conducive data environment (George & Leite, Integrated Social Information Systems and Social Registries, 2019). As shown in Figure 1, it ranges from structural and institutional change to a shift in personal attitude and behavior:

(i) A legal framework that clearly establishes guiding principles for management, defines roles and responsibilities, sets security and protection standards, and outlines necessary arrangements for human resources across the public sector, while addressing potential overlaps with other laws and ensuring inter-agency coordination.

(ii) A data governance and infrastructure system that defines protocols for data security and protection, data access, interoperability, infrastructure requirements, and the management model. This system should be grounded in the guiding principles outlined in the legal framework.

(iii) A strong political will and a dedicated political champion to drive the initiative.

(iv) A team of dedicated, skilled, and technically proficient human resources to manage and operate the system.

(v) A robust strategy to promote cultural change and raise awareness among public sector employees, overcoming the legacy of entrenched paper-based practices and fostering the adoption of a data-centric culture.

Although the aforementioned requirements may appear straightforward, their implementation is highly complex, as "the devil is in the details." The following section examines the key issues that could pose challenges in establishing a National Unified Registry.

2.1. A Holistic Approach to the Public Sector Amidst the Rise of the Digital State

Going the extra mile to cover informality might be controversial. The traditional approach[2] relies on systematic assessments and preparations to reach out to and cover informality. The requirements associated with the diverse functions of the National Unified Registry (NUR) include enhancing the transparency of the contributory scheme and targeting social safety net programs. To effectively extend outreach to workers in the informal sector, those informally employed within formal sectors, and individuals in non-standard employment relationships (such as gig workers, freelancers, and part-time employees), a comprehensive and efficient mechanism is crucial. The challenge lies in the substantial preparatory work needed upfront, which involves defining, listing, and categorizing various forms of employment informality. This task is further complicated by the outdated Labor Code and the fragmented social protection framework, which leaves legal gaps, especially with the emergence of new types of work.

An alternative approach, inspired by nudge theory and choice architecture, could be considered. This method would involve creating eligibility criteria and benefits designed to incentivize informal workers to transition into formal employment structures. By subtly guiding their decisions, informal workers could be “nudged” into formalization without the need for coercive measures. While this approach may seem more efficient, it raises concerns regarding equity. Many workers in informal or non-standard employment are already vulnerable, and systematic exclusion from benefits could exacerbate their social and economic challenges. Therefore, while nudging may facilitate formalization, it must be carefully balanced with consideration for those who could be further marginalized by such a system.

Establishing a data-friendly environment across the public sector is equally a pre-requisite and a major challenge. Transitioning to a NUR requires substantial infrastructural and technological capabilities, along with significant public investments. However, these efforts could be delayed or compromised by tight fiscal constraints and notable efficiency gaps. Additionally, there is a pressing need to enhance the digital infrastructure and build the digital skills of both recipients and providers of social protection services. This is crucial to meet the demands of specific functions such as reporting, data collection, preservation, sharing, and ensuring data privacy and confidentiality. With the increasing prevalence of digital bureaucracy and the rise of the digital state, these technological, ethical, and cultural challenges may currently exceed the capacity of Lebanon’s financially strained state, as well as segments of the population facing the digital divide—particularly older individuals, migrant workers, people with low education levels, and NEETs (Not in Education, Employment, or Training).

Setting a functioning legal and institutional arrangement is the first safeguard for successful implementation. Given the complex interconnections between fiscal adjustments, labor policies, and social protection reforms, the establishment of a NUR in Lebanon may exceed the capabilities of public and institutional actors. It requires a comprehensive overhaul of the public sector, addressing both its internal structures and its interactions with civil society and citizens. Consequently, advocating for the NUR presents an ideal opportunity to rethink Lebanon's current and future governance models, aligning them with the global shift toward the digital state.[3]

2.2. The Potential of Interoperability and the Spillover Effect

The fiscal registry, the civil registry, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the ID system, and other registries offer a wealth of data that can support an efficient profiling and targeting mechanism. In fact, fiscal self-declaration[4] plays a crucial role in establishing a database of employed and unemployed individuals[5] and might be leveraged to collect data on non-registered taxpayers if rendered mandatory by default and linked to other registries.

A NUR that systematically connects with these other registries allows the government to compile a comprehensive dataset of individuals who are partially unemployed, seasonally employed, or working in informal sectors, including those informally employed within formal sectors. This registry can also match individuals with social, fiscal, and wealth attributes, providing invaluable information for more precise targeting, effective enrollment, and addressing tax evasion. By improving the collection of fiscal data, a NUR could substantially increase employers' contributions to the social protection system. Even within the current framework for income and fiscal declaration, a NUR could significantly enhance state revenues. Furthermore, interoperability would improve internal operations within social security and other state agencies in terms of control, audit accuracy, procedural duration, and service quality. Ultimately, citizens would benefit from the cost savings and simplification brought by the establishment of a one-stop shop.

2.3. A Revised Setting to Meet the Requirements of Data Management

The potential outcomes of integration and interoperability could be reached under the condition that all stakeholders (the various public and private institutions involved in the process of data collection and consolidation, as well as individuals and businesses) are able to coordinate, provide, share, or consolidate accurate and timely information, ensuring that the various registries reflect the most current and relevant data.

In fact, a NUR empowers various social protection institutions to optimize both their costs and revenues. On the one hand, social insurance and publicly managed social assistance funds should be capable of uniquely identifying each resident through a specific identification number. This enables tracking various reimbursements, coverages, and assistance, ensuring a continuum between contributory and non-contributory schemes, while preventing duplication and depletion of public funds. On the other hand, mutual funds, other private third-party payers, private institutions, and international organizations would also utilize this unique ID number to report their beneficiaries and the level of assistance received by each. This unique identification not only enhances transparency in the overall macroeconomic social transfers system but also establishes unified standards and criteria for defining social protection floors and targeted social safety net programs.

The most critical questions, however, remain: How can the state create an environment conducive to effective data management? Should this be achieved through gradual bilateral pairing between institutions, or should it follow a top-down approach that establishes a universal data management framework? If the latter approach is chosen, what is the most effective and practical method for collecting and identifying the necessary requirements?

2.4. The Prominent Risks of Ethical Challenges

A major weakness in the current social protection landscape is the lack of systematic indicators to define eligibility for non-contributory schemes. There are also significant challenges in establishing fair and consistent outreach methods for selecting beneficiaries. This issue is faced not only by state-run programs but also by humanitarian organizations, which encounter a "legibility" problem behind the ongoing "eligibility" debate. This stems from the ambiguity and arbitrariness in defining, categorizing, and bureaucratically using (and sometimes manipulating) collected data (Cowling, 2020).

In the existing social protection framework, both current and prospective national initiatives, such as the National Poverty Targeting Program (NPTP), the Emergency Social Safety Net Program (ESSNP), and ambitious humanitarian programs consistently encounter challenges arising from the lack of clarity and transparency in information concerning their target groups. Terms like 'vulnerable,' 'precarious,' and 'poor' undergo constant negotiation between service providers and recipients, often resulting in a 'moral economy of lying.' This occurs when recipients feel compelled to conform to fluctuating and arbitrary definitions imposed by various public or private care programs. To improve resource allocation in non-contributory programs and strengthen their integration with contributory schemes, preparatory efforts to establish a National Unified Registry (NUR) must address bureaucratic definitions and classifications. This requires harmonizing and clarifying these terms across care providers and third-party payers, promoting transparency, and ensuring beneficiaries' right to information. A comprehensive NUR approach necessitates collaboration across various ministries and regulatory bodies, including the Ministry of Public Health, Ministry of Social Affairs, Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Interior and Municipalities, Ministry of Education and Higher Education, the National Social Security Fund, and civil service and military cooperatives. This collaboration should go beyond data sharing and consolidation, focusing on co-developing common standards, bureaucratic tools, and strategies.

2.5. Technological Challenges: from the Software to the Hardware of Data Privacy

The security, confidentiality, and privacy of data must be safeguarded through the use of technology. However, Lebanon's existing surveillance system, which is marked by consistent violations of privacy, coupled with vulnerabilities in its cybersecurity infrastructure, poses significant risks. These vulnerabilities increase the likelihood of breaches and cyber-attacks that could compromise citizens' privacy and intimacy. While the Lebanese Constitution does not explicitly guarantee privacy as an inviolable right, it does protect the sanctity of the private home. Furthermore, public spaces and platforms, such as universities and newspapers, are protected from state intrusion in the name of freedom of expression. Despite this, national security concerns or alleged threats to security often lead to the erosion of privacy, as police forces, paramilitary groups, and militias—operating beyond the control of legal authorities—freely infringe upon citizens' private lives (Kosmatopoulos, 2011).

Much like the fragmented social protection landscape, Lebanon's security and surveillance environment is also defined by a multitude of actors with overlapping jurisdictions. In addition to non-governmental, de facto forces that impose surveillance on the state, several state entities are involved in digital data monitoring. These actors often have conflicting mandates and are vulnerable to political interference, particularly from influential political parties.

Box 1: High Political and Security Risks

How can a NUR be protected from hacking and cyber-attacks? Cybercriminal activity undeniably represents a persistent global threat, particularly as digitalization becomes increasingly integral to public administration and is anticipated to grow with the rise of the digital state. However, when transitioning from software to hardware in data protection, it becomes clear that the primary challenge lies in the lack of political will. A NUR would be subject to the same risks as any other data management system that remains inadequately protected by current legal frameworks. The key question, then, is how can institutions and authorities entrusted with sensitive data effectively safeguard it against malicious external actors?

2.6 Political Control, Institutional Mandates, and Communitarian Considerations

Past efforts to unify or integrate information systems within the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) offer a useful example of the political risks involved. Even seemingly neutral tasks, such as consolidating educational data—which might not initially appear to have significant political or security implications—often become entangled in struggles for control within the same administration. This frequently leads to a more fragmented system than the one MEHE originally sought to resolve. As outlined in the latest MEHE strategy:

“Over the past three years, substantial progress on SIMS[6] and collection of quality data was made; every student in public (except second shift) and private school in general education was allocated a unique student ID, which will help with the tracking and management of their academic path. However, until recently, the information systems of the Center for Educational and Research Development and the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (including the Program Management Unit [PMU] overseeing the second shift) remained fragmented” (Government of Lebanon, 2021).

The challenges faced by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) are just the tip of the iceberg in an administration reluctant to share data across its departments. These challenges highlight the urgent need for a comprehensive approach to public data management, advocating for a holistic and integrative reform of the public sector. The manipulation of data is intricately tied to ongoing negotiations regarding the roles, functions, and mandates of various public institutions. National data—such as birth registries, death certificates, and labor market information systems—has consistently been treated as sensitive to national security, restricting access even for policymakers. Control over economic, social, and demographic data plays a critical role in reinforcing or undermining the political power of the central state, directly influencing the political structures that shape power dynamics within civil society. This data is often used as a tool to maintain opacity in economic and financial transactions, aligning with the interests of groups and local authoritarian parties seeking to consolidate and obscure their control over public institutions.

Moreover, Lebanon has not conducted a national census since 1932, largely due to the country's complex sectarian composition and the delicate balance of power among its religious communities. A new census could reveal shifts in the sectarian makeup of the population, carrying significant political implications. If the demographic balance has changed, it could prompt demands for adjustments to Lebanon's power-sharing system, which allocates political and administrative positions according to religious affiliation. There is also concern that any census could be manipulated for political gain. Given Lebanon’s history of corruption and political maneuvering, there is widespread skepticism about whether the results of a census would be used fairly or transparently.

A commonly adopted political stance in response to these concerns focuses on the perceived destabilizing effects an improved information system could have on the fragile religious and sectarian equilibrium. This perspective is rooted in a historical demographic assumption that political power should be distributed among communities in proportion to their perceived demographic weight, though not always in practice, particularly with regard to the most significant communities. Unpacking these political discourses and revealing the implicit intentions behind them lies beyond the scope of this work. Further research is needed to explore the political construction of data in Lebanon and its central role in shaping and perpetuating the existing structures of dominance.

Section 3: What are the Design Options for an Integrated Information System for Social Protection in Lebanon?

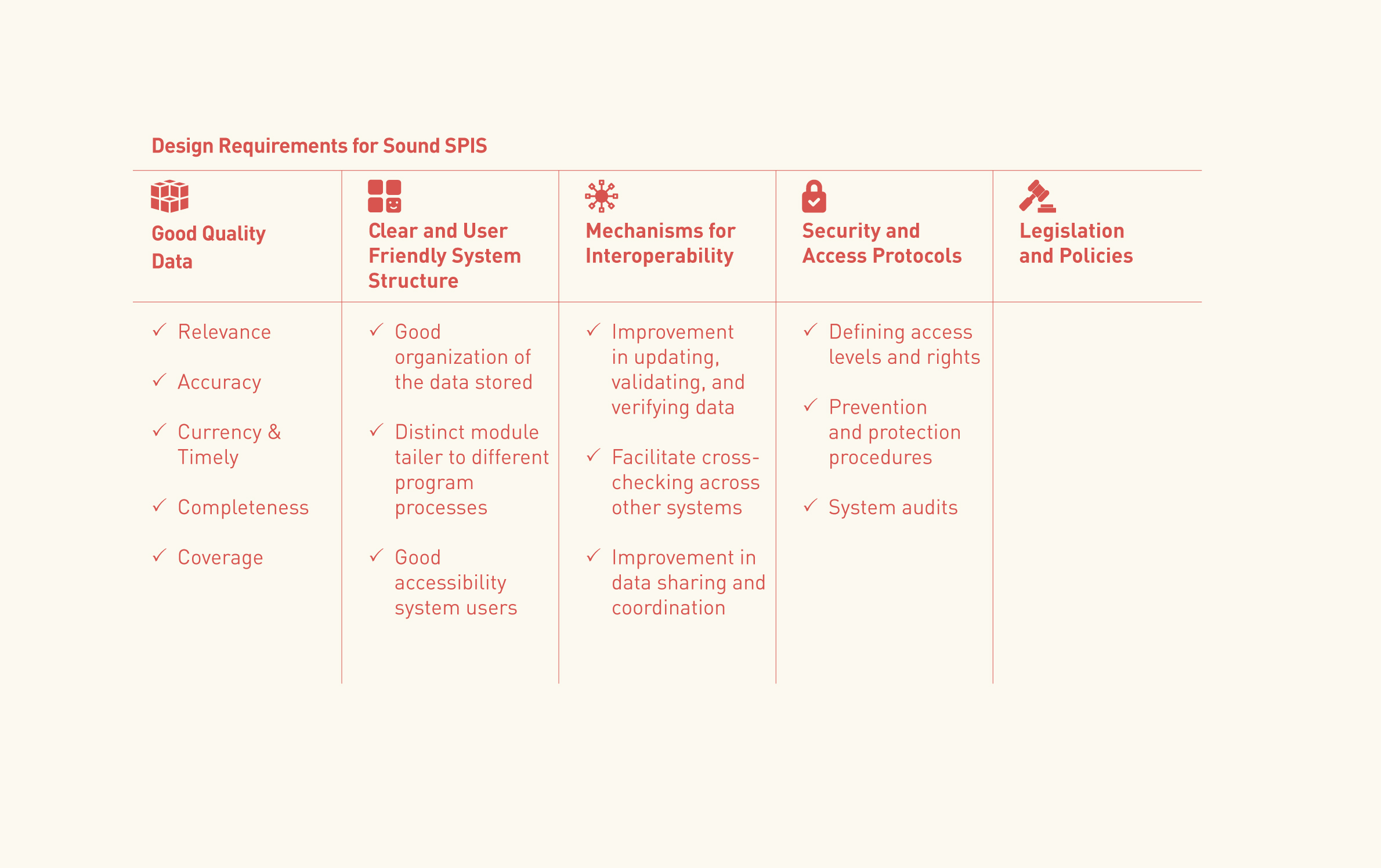

In the context of Lebanon, designing a tailored Integrated Information System requires a nuanced approach, given the specific set of challenges unique to the country, including a legacy of resistance to data sharing among governmental departments, particularly those involving security forces. A customized approach must carefully address these challenges by focusing on establishing robust legal frameworks, trust-building measures, and ethical data practices. The design should also account for public resistance, ensuring informed consent, while acknowledging the interconnectedness of data sources. Additionally, fostering collaboration among ministerial bodies and public third-party stakeholders is crucial. The system's success will depend on its ability to navigate these country-specific complexities, while promoting a holistic and transparent approach to public data management (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Design Requirements for Sound SPIS

Reference: Williams & Moreira, 2020.

3.1. Finding the Balance between Full-scale Reform and an Incremental Approach

Implementing a full-scale approach for the NUR involves deploying the entire system at once, offering a comprehensive solution but potentially introducing higher risks and challenges. A holistic approach would necessitate simultaneous reforms across the public sector, as outlined in previous sections, including the establishment of a labor market information system, tax administration reform, and the adoption of social policies oriented toward universality. Additionally, reforms related to data security and protection would need to address the fundamental structures of the judiciary and military/security apparatus.

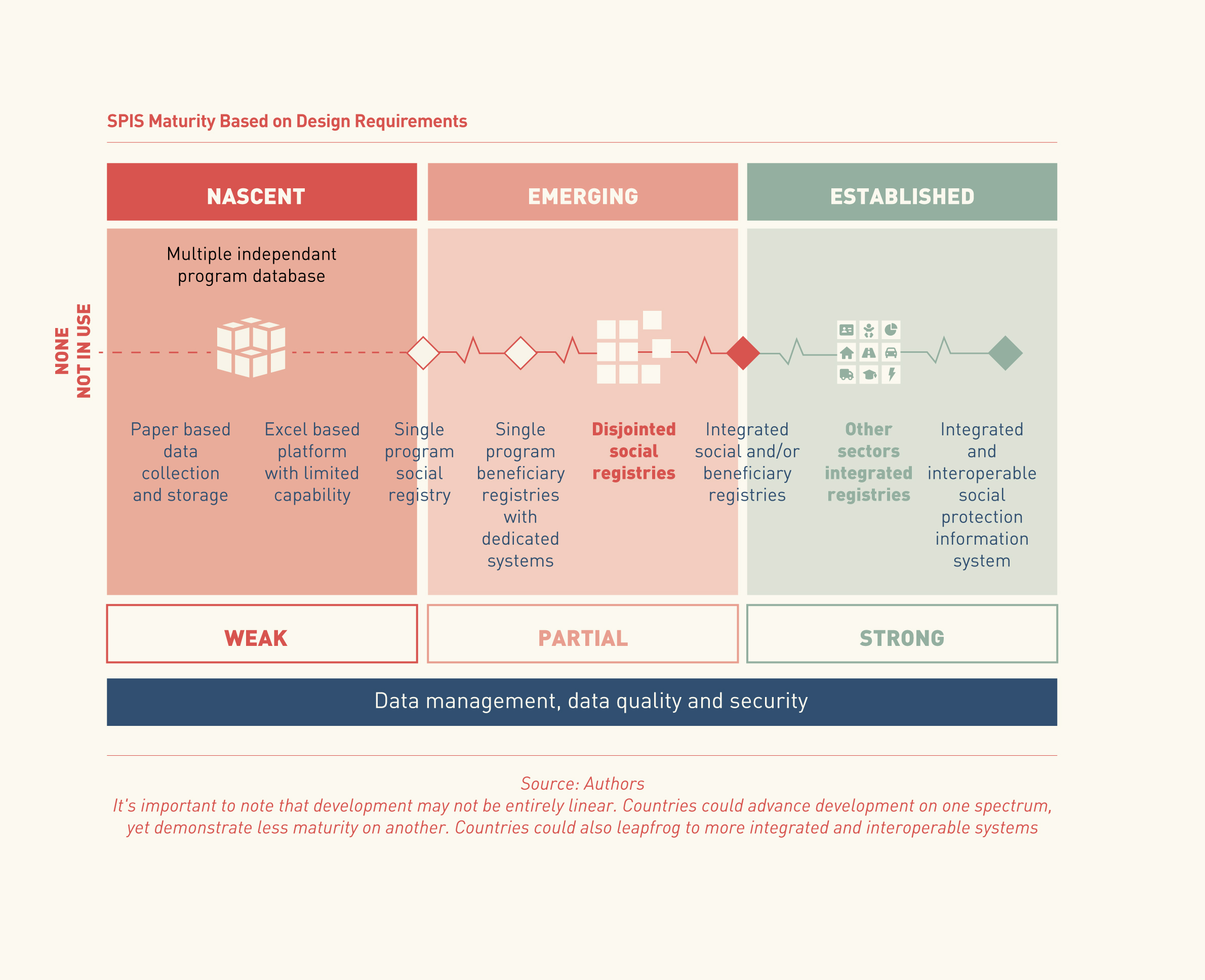

Alternatively, an incremental approach entails phased implementation, enabling gradual adjustments and adaptations over time. This method may be more suitable for Lebanon's context, where concerns about potential disruptions and limited resources are prevalent. Such an approach would allow for sequential stages of reform, testing, and refinement in the unification, classification, and protection of data. However, it may prolong the overall timeline and increase the risk of jeopardizing the entire process. Past experience, such as with Lebanon’s fragmented educational information systems, suggests that incremental data unification can sometimes be counterproductive, resulting in further fragmentation.

In contrast to incremental implementation, gradual integration may represent a more practical path forward. While still involving a step-by-step process, gradual integration could focus on establishing a unified registry without breaking the entire reform project into smaller, discrete tasks. Empirical evidence from past reforms in Lebanon demonstrates that political interference in one domain often results in blockades or stagnation in others, potentially halting or undermining the entire modernization effort (Makdisi, Kiwan, & Marktanner, 2010). For example, the Jordanian government has recently adopted a similar strategy for its National Registry, using an integrated approach that links information centers across various sectors within a national information network (Government of Jordan, 2024). However, a comprehensive evaluation of this strategy is still lacking, particularly since the Jordanian NUR is neutral and not linked to social protection program databases.

Similarly, Italy opted for a gradual integrative strategy at the municipal level to achieve its Unified National Population Registry (Datta, 2020), aiming for a "one municipality of 60 million residents" (Calvaresi, 2018). Additionally, the decade-long experience of Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries in establishing social protection information systems has shown that most countries chose a gradual approach to digitization, improving quality and accuracy, integration and data sharing, security, and key registries. Figure 3 illustrates the stages of information system maturity, acknowledging that reform development is rarely linear; for instance, integration may occur across single programs, across multiple programs, or even without integration within a single program for the beneficiary registry (Williams & Moreira, 2020).

Figure 3: SPIS Maturity Based on Design Requirements

Reference: Williams & Moreira, 2020.

3.2. The Delicate Task of Designing a National Unified Registry

Designing a proper framework and plan would require considering multiple aspects:

(i) Build on what exists without compromising the effectiveness of the solution. For instance, the Unified Identification Number Law (No. 241 dated October 22, 2012) and its corresponding Decree (No. 168 dated February 17, 2017) assigned the sole responsibility for issuing and managing the Unified Identification Number to the Directorate-General of Civil Status at the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. This law cannot be overlooked when conceiving a national unified registry for Lebanon. A couple of other existing laws might affect the design of a NUR and should be taken into consideration, such as the E-Transactions and Personal Data Law (No. 81 dated October 10, 2018), the Consumer Protection Law (No. 659 dated February 4, 2005), the Lebanese Government Interoperability Framework (LGIF) and the Lebanese Government Interoperability Reference Architecture (LGIRA), and the unique ID Decree No. 168 issued on February 17, 2017, which set the rules and modalities for the adoption of the Unique ID Number in the public sector.

(ii) Safeguard the vision articulated in the NPSP, which is to “establish mechanisms and platforms for data sharing and the related validated institutional architecture.” This requires, as per the NSPS, to put two reform trajectories in motion: 1) to ensure integration between various existing registries or databases across different social protection pillars; and 2) to enable interoperability with other public institutions (such as the civil registries, fiscal registry, commercial registries, and others). It is extremely important, during the design phase, to clarify what is meant by a national unified registry and what it covers. Is it a neutral NUR that does not relate to social protection (similar to Jordan)? Or is it a NUR that feeds the SPIMS?

(iii) Avoid the trap of social registries. It is crucial to build on existing efforts as mentioned previously, yet policy tinkering might be delusional. In fact, the ESSNP includes the development of a NUR as part of the loan granted by the WB to the government of Lebanon. The NUR, as conceived in the ESSNP, starts as a targeted social registry benefiting the poorest and is expected to widen in scope to cover more SP programs and integrate more functions. Governments in dire fiscal conditions tend to agree on such an approach for multiple reasons, including: (1) the lack of resources, while the need for an information system supporting SP programs is a must. Therefore, it is better to have a targeted registry than having no system at all and consequently no SP program, and since a larger integration might be more complex and costly; and (2) social registries related to social assistance programs might be financed through loans (like the ESSNP), and it is widely recognized and strongly recommended to build on a product (or not to waste a product) that was paid for by taxpayers money.

Unfortunately, international experiences show that targeted registries are doomed to fail (Kidd, Athias, & Mohamud, 2021). In fact, data collected through proxy means testing is “undertaken at a particular point in time” and not updated until the next data collection process. Therefore, targeted registries are designed with an underlying assumption that “we live in a static world,” while the household structure and conditions could change rapidly. As a matter of fact, social registries, also known as targeted databases, cannot evolve to become a NUR.

Box 2: The Clash of Paradigms

Given the complexity of Lebanon's governance and political system, a gradual approach to implementing the National Unified Registry (NUR) appears to be the most appropriate strategy. However, this approach still requires a comprehensive, actionable, and up-to-date framework for data integration that outlines the requirements for upgrading information systems, establishes compatibility criteria, and defines integration parameters. This means that while the system should not be designed incrementally, its conceptualization must occur beforehand by a designated state entity, with gradual enforcement taking place over subsequent stages.

Although a data integration framework may appear to be a technical issue, it is, in reality, primarily a policy and political challenge. It will need to address a range of complex considerations, such as securing political consensus on the ultimate objectives of integration, determining the scope of data to be integrated, and establishing clear access and rights protocols for program administrators. Furthermore, any integration plan must be developed in alignment with the government's priorities and the available human and financial resources. These factors are critical in determining the sequence in which programs will be integrated and the extent of interoperability—whether it will extend across all external registries or be limited to key databases, such as civil registries and fiscal records. The plan will also need to synchronize digitization efforts within specific ministries with the potential requirements of the national integration framework. Above all, the integration priorities must be closely aligned with the National Social Protection Strategy and its corresponding action plan.Ultimately the integration plan should be the result of the following phases:

1. Championing: A designated entity should oversee the design and implementation of the integration plan, while making sure all stakeholders are on board and bottlenecks are being resolved properly. This entity shall not be under the direct control of one ministry, but rather emanate from an inter-ministerial agreement/committee.

2. Assessing the ground: Conducting an institutional mapping and methodical assessment of existing systems and available datasets. SP providers that might be subjected to the assessment could be prioritized based on the scale of their coverage and the depth of their data. A realistic approach, for instance, would be to cover key entities/programs first, such as the NSSF, NPTP and ESSN, fiscal and commercial registries, and internal security registries, in order to collect the technical requirements that will form the basis for the common system. Other mutual funds, SP providers, or state entities will have to adapt to meet the new system’s requirements.

3. Designing the intervention: Based on a participatory approach, the lead agency will have to develop an action plan that sets the steps, priorities, and deadlines for the integration processes.

4. Implementation: This includes drafting an appropriate law and secondary legislation, developing guidelines and manuals, setting the infrastructure and technical requirements and ensuring compliance, as well as developing security, protection, and access protocols, among others.

Figure 4: SP Service Delivery Chain

Source: George & Leite, Integrated Social Information Systems and Social Registries, 2019.

Figure 5: Transitioning from Siloed Social Registries to an Integrated Social Registry

Source: George & Leite, Integrated Social Information Systems and Social Registries, 2019.

Section 4: Recommendations

This section provides general recommendations and guiding principles to support a potential transition towards a National Unified Registry. It excludes policy and design recommendations as the latter require extensive and participatory national consultations and policy discussions.

Institutional Governance

▪ The provision of SP services is a cross-cutting function across multiple public sector organizations (MoSA, NSSF, PCM, mutual funds, MoPH, etc.). The NSPS has indeed acknowledged that “one of the core challenges for realizing [its objectives] is the governance and institutional framework for its implementation” (Government of Lebanon, 2023) and has proposed multiple policy options to revamp the institutional arrangements based on the pre-defined SP pillars. Beyond the issue of service provision, the usage and management of data directly or indirectly related to SP services requires the involvement of other state entities that are not providers of social services, such as the MoF, the ISF, etc. In fact, another layer of institutional governance overhaul is required to set a solid base of data management and integration. The digital strategy developed by OMSAR could be a starting point for a national discussion as it lays the foundational principle for the digital governance model, roles and responsibilities, and the governance structure (OMSAR, 2022).

▪ Ultimately, a new governance structure and revamped coordination mechanisms should extend beyond the public sector, since most SP services are provided by non-governmental organizations that are facing the same level of fragmentation. Increasing the level of integration is key to accurately responding to rising needs and external shocks.

▪ Building trust between institutions is a key pillar to any revamped model. This requires a clear framework for data sharing and access with well-defined roles and responsibilities.

Data Governance and Infrastructure

▪ Establishing and enforcing a framework for data governance, encompassing structure, accessibility, transparency, security, and privacy, is essential. Lebanon has a history of formulating strategies for digital transformation, spearheaded by OMSAR. These include the National Information Technology Strategy (1998), the National ICT Policy and Strategy for Lebanon (2001), the first E-Government Strategy (2002), the National e-Strategy document (2003), the updated E-Government Strategy (2008), the Lebanese Government Interoperability Framework (2016), the High-Level Digital Transformation Strategy (2018), and the Digital Transformation Strategy and Implementation Plan 2020-2030 (2019), with a revised version released in 2022 (OMSAR, 2022). While these strategies have outlined the governance model, foundational principles, interoperability framework, and other key elements, none have been successfully implemented. The primary challenge hindering the gradual integration and pairing of social protection providers' and stakeholders' respective information systems is the absence of an updated, actionable framework for data governance.

▪ One of the primary challenges in establishing new social protection (SP) programs, particularly social assistance, is the absence of up-to-date databases and systems. Public institutions face the dual task of building and upgrading these systems while simultaneously delivering services, as exemplified by the Emergency Social Safety Net (ESSN). It is crucial that a robust data infrastructure is established upstream, as even in the absence of comprehensive data governance and structural frameworks, SP service providers must still be able to store and manage data. Additionally, they need to operate essential functions such as payment modules, monitoring, evaluation, and other core activities.

Data Protection and Privacy

▪ Hosting all social data inside the country is a pre-requisite to ensure data security. In fact, many ministries store their data on clouds, while most countries host their social registries with the national telecom operator. Fortunately, Ogero has a data center that is currently hosting the data generated by DAEM and IMPACT and that has the capacity to host other state-owned and state-managed databases free of charge.

▪ Yet, such an initiative should be complemented by a comprehensive legal framework specifying the rights and obligations concerning data protection and privacy. The effectiveness of this legal framework depends on enforceable sanctions. Indeed, historical instances reveal that despite the drafting of many protective laws by Lebanese legislators, they often remained ineffective or became opportunities for discretion and overstepping, ultimately eroding the impact of the law or normalizing its infringement. Thus, clear policies regarding data governance, usage, and protection would lack effectiveness unless they are complemented by stringent controls, inspections, and sanctions.

▪ If the state is expecting all citizens to entrust it with valuable personal (and intimate) information, it becomes evident that trust is fundamental to the success of the NUR. Establishing trust in the confidentiality of data requires the state to provide assurances that the information will never will be exploited for commercial purposes[7] (Privacy International, 2019) and that intimate information, such as health status, which citizens may be hesitant to share even with close persons, will not be commodified or manipulated to influence election campaigns in a country where the electoral law is typically subjected to intricate oligarchical negotiations to define tailored electoral circumscriptions.

▪ Any National Unified Registry (NUR) should be reinforced by accountability mechanisms that entail consequences for violations of ethical data practices. To ensure effectiveness, these mechanisms should address existing and overt breaches of the – somewhat constitutional – right to privacy while simultaneously progressing towards the implementation of the NUR.

▪ Any National Unified Registry (NUR) should be based on informed consent and transparency. Individuals must provide informed consent before their data is collected or shared. This necessitates clear communication and transparency regarding the purpose, scope, and implications of data usage, ensuring citizens are well-informed of the data collection process.

▪ Establishing a National Data Protection Authority is also key to enforce data protection and privacy. This entails the appointment of data protection officers, the enforcement of specific technical security measures, the implementation of a system for breach notification, and, most importantly, the introduction of administrative enforcement actions to ensure that citizens and victims are entitled to resort to the competent courts for matters related to the enforcement of their rights under the law (DLA PIPER, 2022).

▪ Lastly, legislators should establish explicit criteria and sanctions concerning the anonymization and de-identification of personal data to safeguard individual privacy. In Lebanese culture, individual privacy is not always regarded as a sacred, intimate sphere. Jürgen Habermas, in his seminal work on the public sphere (Habermas, 2020), highlights that our valuation of public and private spheres is not solely based on moral or cultural judgments but also rooted in the political economy of the public space, thus referring to the historical formation and distinction between these two fundamental dimensions of social life. In a nuanced interpretation of Habermas's concept of the public sphere, it could be argued that Lebanese citizens find themselves in a two-front battle. On one front, they are contending with persistent and escalating intrusions into their private matters by the state, religious groups, family, and community. On the second, they aspire to reclaim public spaces and quasi-privatized public institutions.

Political Will and Buy-in

▪ Political will and buy-in are the most important starting points. The political authorities will have to answer a set of questions that are key to define and shape any integration strategy and action plan. Among these questions are the following: What are the primary databases to be selected for the 1st layer of integration? What is the ultimate purpose of integration? Is it for the sake of having an integrated social registry or for developing a comprehensive social assistance program or social protection program? Which state entity will be managing all data? Is it an existing entity, such as MoSA, the Inter-ministerial Committee, the Central Administration of Statistics, or should a new entity be established?

Institutional Readiness and Brainware

▪ In the new realm of state operations and logistics, the function of data management has become as important as financial management and human resource management. This should be reflected in the build-up of solid institutional capacity to manage and deal with a larger scale of data generation and capture, through the establishment of data management units across line ministries, professionalizing data management positions in the public sector, and setting a clear competency framework that allows the state to cope with new trends and be ready for continuous changes.

Financing and Sustainability

▪ The transition towards a NUR, encompassing institutional arrangements, laws and regulations, infrastructure, hardware, and human resources, necessitates sustainable financing. It is crucial for public authorities to recognize that the scale and sustainability of financing will significantly determine the strategy for the transition, as well as its implementation timeline and overall scope.

CONCLUSION