Crafting the good citizen, streaming the good king: Notes on press freedom, hegemony and social contention in King Abdallah II’s Jordan

During the mandate of King Abdallah II, press freedom in Jordan has undergone a significant contraction. This has progressively endowed the Hashemite monarchy and its organic incumbents with an unprecedented directive control over the circulation and the framing of events in the country – hence over the capacity to strategically filter from above the diffusion of politically sensitive news, silence voices of political challengers, and orient domestic and international opinion.

This paper aims to provide a preliminary assessment of the role played by the enforcement and the strategic application of restrictions on media freedom in consolidating King Abdallah II’s rule, by scrutinizing how the cumulative strategic application of press restrictions succeeded or failed to validate King Abdallah II's international reputation of a moderate and progressive leader, and legitimize the neoliberal upgrading of the authoritarian bargain with his domestic constituencies.

To cite this paper: Rossana Tufaro,"Crafting the good citizen, streaming the good king: Notes on press freedom, hegemony and social contention in King Abdallah II’s Jordan", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2021-07-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.001.90001

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/crafting-good-citizen-streaming-good-king-notes-press-freedom-hegemony-and-social-contention

Introduction

In recent years, press freedom in Jordan has undergone a significant contraction (Alnajjar 2021). The repressive shift arrived concurrently with the steady rise in contentious mobilizations that the country has been experiencing since 2011, as a result of the progressive degradation of the average living conditions and the state reiteration of tight IMF-backed neoliberal reforms.

Currently, Jordan is ranked 129 out of 180 in Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index (RSF 2021). Following the stringent legislative initiatives which hit online journalism and social media against the backdrop of 2011 Hirak, the independent coverage of local news, as well as the space for a plural political debate on online outlets have experienced a severe blow. Since 2013, on the grounds of the lack of official licensing, hundreds of websites have been blocked. Also, after the enforcement of the 2015 cybercrime law which made the publication of articles and comments liable to penal sanctioning, journalists’ self-censorship significantly increased. Equally important, the new legislative cadre enabled a steady rise in gag orders and arrests against journalists dealing with politically sensitive subjects. Restrictions have further increased throughout the past year, as a result of the re-introduction of the emergency law by the government following the COVID-19 outbreak (Younes 2020). Therefore, access to information has become increasingly dependent on official media sources and state-licensed outlets, which are subjected to strict state surveillance through a variety of legislative infrastructures and regulatory practices. The state is widely present in the national mediascape through a variety of public broadcasting TV and radio stations, and the ownership of stakes in several media corporations (Tweissi 2021, 64-65). State media presence further enlarged in 2018 as a new public-owned all-news broadcasting channel was launched (al-Mamlaka TV). This endowed Jordanian authorities with the highest degree of directive control over the circulation and framing of events in the country ever experienced in the past three decades. The authorities strategically filtered the diffusion of politically sensitive news, silenced the voices of political challengers, and oriented domestic and international opinion, as the lifting of the martial law by King Hussein (1989) inaugurated a phase of timid press liberalization.

From a scholarly perspective, the rationale and the political implications of the waxing and waning of Jordanian press and media freedom have been predominantly investigated in the mirror of the cycles of liberalization and de-liberalization experienced by the Hashemite regime since 1989 (Jones 1998, Najjar 1998, Sakr 2013, Lucas 2003), the latter framed according to institutionalist approaches. Much less attention has been devoted instead to the investigation of the phenomenon in relation to the construction of the performative power of the monarchy’s hegemonic discourse, or to the role that their enactment and strategic enforcement has historically played in underpinning the reproduction of the Hashemite rule.

This paper aims to fulfill this gap by providing a preliminary analytical scrutiny of the role played by the enforcement and the strategic application of the restrictions on media freedom in consolidating King Abdallah II’s rule. After providing a historical overview of Jordanian press freedom policies from King Hussein to the advent of King Abdallah II, the paper will investigate how the latter have been strategized by the monarch to validate his international reputation of a moderate and progressive leader, and legitimize the neoliberal upgrading of the authoritarian bargain with his domestic constituencies before (section 2) and after the challenges of the Arab Uprisings (section 3). It will then conclude with an overview of the performative outcomes that the latter have succeeded or failed to produce. If, as Martinez argues, the capillary occupation of the discursive space by Jordanian authoritarian incumbents plays a fundamental role in maintaining their position by making certain concepts and histories meaningful and acceptable to the citizenry and their international audience (Martínez 2017, 17). To detect where the latter is managing or failing to produce compliance might offer new insights into the micro-dynamics which are underpinning the reproduction of the Jordanian authoritarian regime.

I – From King Hussein to King Abdallah II: A historical overview of Jordanian press freedom policies

Jordanian press freedom has historically waxed and waned according to the political circumstances of the country. The first repressive shift in its independent history arrived in the wake of the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 (the June War). For the first time, a publication law imposed governmental control over the newspapers by compulsory turning privately-owned media outlets into state-participated corporations. This early crackdown was part of a broader process of authoritarian re-entrenchment engaged by King Hussein in response to the challenges to the kingdom’s stability. It was compounded by the political and socio-economic backlash of the defeat of the June war, and above all, the growing popular consensus for the activities of Palestinian guerrilla whose main operational base was within the kingdom’s borders. This re-entrenchment found its most eloquent expression in the re-introduction of the martial law (1967), which banned political parties, suspended elections, and endowed the king and the government with extraordinary executive and legislative powers. The martial law remained at stake after the forced departure of the PLO leadership from Jordan in the wake of Black September (1970). The successive October Arab-Israeli War (1973), the unsolved Palestinian-Jordanian relations with and within the state, the protracted regional instability, and the socio-economic backlash of the oil crisis in the late 1970s maintained the country in a state of permanent, latent ebullition. This constituted a blow to the incipient process of expansion of the Jordanian press inaugurated with the enactment of the 1952 Constitution, to leave room to the consolidation of what the scholar William Rugh defined as a rigidly controlled “loyalist” mediascape (i.e. a mediascape characterized by a pervasive state presence and control, a limited plurality of opinions and coverage of the domestic affairs, and a blatant, choral touting of the government positions (Rugh 1979, 25-29). This cadre began to progressively change from the second half of the 1980s.

In late January 1985, following a televised speech by King Hussein condemning Jordanian media for attacking individuals and institutions, the newly appointed Minister of Culture and Information Leila Sharaf announced her resignation through a public letter denouncing the growing difficulty for officials to guarantee press freedom in the kingdom. The government reacted with a wave of arrests against journalists and a further tightening of the existing restrictive measures. Strict censorship was maintained for the next three years, as the outbreak of the First Intifada (1987) provided an opportunity to maintain the iron fist (Najjar 1998). The bread riots of August 1989 constituted a trigger that initiated a process of liberalization. The riots were sparked by the government’s decision to lift subsidies on wheat, as part of a broader set of IMF-sponsored neoliberal structural adjustments addressed to reduce the deep state deficit and obtain international loans (Andoni and Schwendler, 1996). Since the early 1970s, subsidies had represented a fundamental instrument of hegemonic incorporation for the Hashemite monarchy which, coherently with the rest of the authoritarian regimes in the region, had sought to compensate for the lack of basic political freedoms with the provision of socio-economic rights. Albeit the lift of fuel subsidies in March had already triggered a wave of protests in the southern city of Ma’an, prime minister Rifai was confident enough that a similar intervention on wheat would not lead to an escalation. As demonstrations erupted and rapidly expanded, however, it became clear that to guarantee the regime’s survival, some concessions had become necessary. This has initiated the beginning of a phase of “defensive democratization”, i.e. a phase of carefully controlled, pre-emptive political liberalization designed to maintain the existing core structures of Jordanian power, by strategically enlarging from above the boundaries of political participation (Robinson 1998). By 1992, martial law was officially lifted, and political parties and elections were re-established. In a similar vein, in 1993 a new Press and Publications Law (PPL) was issued, allowing controlled liberalization of the sector.

As stressed by several observers, the PPL of 1993 remained characterized by an authoritarian formulation (Jordan 1998, Najjar 1998, Lucas 2003). The most important disciplinary measures included: the obligation for journalists to be affiliated to the state-controlled Jordanian Press Association, the possibility for the state to arbitrarily revoke newspapers’ licensing, and several substantial limitations on the news content. Those include the prohibition to comment on the royal family, the army, members of Parliament and Jordanian international allies, as well as reporting on matters related to national security, contents of Parliamentary sessions, shaking confidence in the national economy, or publishing any content contrary to public morals (Jones 1998, 85). Nevertheless, its enforcement was sufficient to trigger a flourishing of new outlets and, consequently, a moderate pluralization of opinions. Between 1992 and 1997 the number of licensed publications rose from five to forty, including party newspapers, tabloids, and a variety of weekly periodicals (Najjar 1998, 132). This relatively positive climate, however, was meant to be short-lived. From 1997 onwards, a succession of amendments to the PPL of 1993 tightened once again the margins of press freedom. The first cycle of new restrictions (1997-1998) was implemented against the backdrop of a broader monarchical restoration of the iron first. This was triggered by the surge of two waves of popular riots (1996 and 1998, respectively), during which many political events such as the Parliamentary elections of 1997, the widespread delusion for the normalization of the relations with Israel and its meagre gains, and the delicate bargaining for the succession to the throne, made the palace increasingly intolerant towards socio-political opposition (Robins 2019, 202-209; Lucas 2003, 87-93). The first wave of riots occurred in August 1996 in Ma’an, spreading later on to the rest of the major provincial towns and the capital. The riots were sparked by a steady rise in the bread prices, to a backdrop of soaring discontent triggered by years of IMF-backed austerity policies (Ryan 1998; Adoni and Schwendler 1996). The second wave remained limited to Ma’an and was ignited by the opposition to the missile attacks launched by the Clinton administration against Iraq (Schwendler 2002). In both cases, the scope of the grievances including demanding the government’s resignation largely surpassed that of their immediate triggers, to question the very heart of King Hussein’s economic, social, and foreign policies.

It was after the succession of King Abdallah II to King Hussein in 1999 that repressive legislative initiatives peaked.

Aged 37 at the moment of his ascension to the throne, King Abdallah II inaugurated his mandate under the banner of promises of modernization and liberalization. Amid this reformist momentum, the privatization of the national broadcasting sector became soon one of Abdallah’s flagship programmatic goals, who seemed eager to align Jordanian press to the international transparency standards and turn the country into a prominent regional node for international broadcasting (Sakr 2013, 100-102). However, the numerous initiatives undertaken in this sense soon revealed nothing but a Trojan Horse. In 2001, the Ministry of Information was dismantled per royal initiative and a Media Free Zone for international press was established in Amman. An amendment of the Penal Code imposed restrictions on freedom of expression for all the individuals operating within the kingdom’s territory. This included the sanctioning of any alleged defamation against the royal family, the security apparatuses, the Parliament, and Jordan’s international allies, as well as any act “undermining Jordan’s political system, inciting opposition, or attempting to change Jordan’s economic or social systems” (ICNL 2019). In a similar vein, while the Audiovisual Media Law of 2002 broke the state monopoly over TV broadcasting, the same law extended the most salient content restrictions already at stake for the press to the licensed private televisions (Sakr 2013, 104). Finally, while in 2007 Jordan approved the first Right to Access to Information Law in the region, its concrete application remained de facto a dead letter, and the capillary meddling of security apparatuses on the exercise of journalistic activity continued to prosper (Tweissi 2019, 121-122).

The result was to constrain the proliferation of new media outlets (private TVs, radio stations, satellite channels) within a climate of deliberately pervasive but vaguely defined red lines, incumbent sanctioning, and coercive bureaucratic and licensing requirements, that effectively leads to self-censorship underlying any coverage of Jordanian domestic affairs.

Jordanian officials justified the apparent contradiction between formal openings and tighter content restrictions with the pretext of the global War on Terror ignited by the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York, at a moment when the Second Intifada (2001), the US invasion of Iraq (2003), and its political and economic backlash, constituted important challenges to the stability of the regime. As a matter of fact, it was instead fully paradigmatic of the two-folded strategy through which King Abdallah II ultimately sought to consolidate its leadership. On one side, an autocratic re-entrenchment of the kingdom’s power structure by renovating the historical ruling partnership between the monarchy, the army, and Transjordanian constituencies. On the other, a commitment to democratic reform and modernization fostered through contained pluralism and the adoption of periodical national development campaigns, serving the triple purpose of providing legitimation for the king’s acceleration of Jordanian neoliberal transition, consolidating his international reputation of enlightened regional leader, and possibly enlarging his power base. Within this broader framework, press restrictions were applied not only as repressive means to clamp down on dissident voices or silence scandals, but, more importantly, as a fundamental disciplinary dispositive through crafting from above the narratives of the country.

II – From “Jordan First” to the 2011 Hirak: National narratives, social changes, and autocratic re-entrenchments during the first decade of King Abdallah II’s kingdom

Since his ascension to the throne, King Abdallah II’s efforts to reconcile the construction of a solid power base with the implementation of a neoliberal agenda represented a challenging balancing act.

Following the specific articulation of the Jordanian independence process and the country’s ethno-national peculiarities, the political rule of the Hashemite monarchy has historically been underpinned by the loyalty of the rural East Banker population and its tribal political elites, against a population composed for the most part by urbanized Palestinians. Especially throughout the 1970s and 1980s, this loyalty was cemented by providing East Bankers with sustained social provision and secure employment in the expanding public and military sectors, compounded by the incorporation of East Bank political-economic elites in the ruling apparatus, the security services, and the state enterprises. The reproduction of this power structure was enabled by the influx of foreign-generated revenues in the national economic circuit, in the form of diaspora remittances and foreign aid fed by the Gulf oil boom. When the debt crisis of the late 1980s compelled King Hussein to defer Jordanian economic policies to the IMF, the monarch managed to reassemble the social contract with his target constituency by tilting the political openings of the 1990s in favor of East Bankers and the incipient, but contained, privatization of strategic state assets (Greenwood 2003a). At the same time, cuts on subsidies and welfare expenditure were partially compensated by East Bankers-tailored ad hoc programs for low-income households (subsidies, micro-entrepreneurship), and, above all, the militarization of the provision of welfare services, operated by expanding the military budget and devoting it to the enhancement of labor and social benefits for military personnel and their families such as pensions, housing loans, scholarships, healthcare services, and military cooperatives (Baylouny 2008, 301-302). The private outsourcing and the militarization of welfare further expanded under King Abdallah II who, concurrently with the acceleration of Jordanian neoliberal transition, increased military personnel by establishing new police bodies, and reconfigured the pattern of military expenditure by recanalizing the budget for heavy armor and artillery towards the construction of a business-oriented domestic defense industry producing equipment and providing services, research, and training at national and regional levels alike (Baylouny 2008, 302; Marshall 2013; Tell, 2015). King Abdullah II further consolidated the embedding of the intelligence agency (mukhabarat) in the state apparatus and maintained the electoral laws tilted in favor of loyal elites. This was paralleled by the king’s attempts to incorporate a new middle class of young, highly-educated East-Bankers (the so-called Generation Abdallah) in the core social base of the regime. He fostered their direct participation in the state-sponsored processes of political and economic liberalization via national development and human rights committees, social enterprises and NGOs, king-sponsored prizes and awards, high education programs (Kreitmeyr 2019; İşleyen and Kreitmeyr 2021).

The legitimizing framework for Abdullah’s upgrading of Jordanian neoliberal bargain was provided by the periodical launch of large state-sponsored campaigns of national development, whereby the king sought to embed the new country’s economic and foreign policy imperatives in the ‘authorities of delimitation’ defining Jordanian national identity. The blueprint for this identity redefinition was set up with the 2002 Jordan First campaign.

The initiative was solemnly launched in the late month of October 2002, during which the looming discontent over a new package of indirect taxes, the fears of an incumbent new war on Iraq, and the assassination of the USAID operator Laurence Foley by an Islamist group in Amman, triggered a surge of social tensions in the monarchy’s historical southern bastions (Schwendler 2002). The king presented Jordan First as holistic philosophy governance aiming at building a new social accord among Jordanians by forging national “unity in diversity” through the enforcement of inclusive democratic reforms and the reformulation of the state-individual relationships by assuming public-private partnerships as the main engine for socio-economic development (Jordan Politics – Jordan First).

As stressed by al-Oudat and Alshboul, the overall aim of the campaign was to prepare Jordanian citizens for the rapid social and political changes that the country would have experienced in the years to come, whose main outlines were largely anticipated in the roadmap that the king sketched in his explanatory speeches (al-Oudat and Alshboul 2010, 81-82). The main rhetorical artifice whereby he sought to institute the neoliberal recrafting of the Jordanian civil order as a new distinctive feature of the Jordanian national identity, was to frame the total adherence to his new ‘philosophy of governance’ as the supreme act of loyalty performable by citizens to the homeland and its highest interests, hence, as the minimal common denominator separating the real, devoted Jordanian from an unpatriotic pundit (King Abdallah II 2002). In doing so, the king also set the boundaries for the authorized language of political action and dissent, providing the Palace with the legitimizing framework to repress, discredit and/or exclude from decision-making any political actor not fully aligned with the royal agenda. The absolute identification of Jordan with the king’s vision was further underpinned by the incorporation of the distinctive features of King Abdallah II’s language of neoliberal reform in the stability and exceptionalist tropes whereby the Hashemite monarchy had historically crafted his self-representation (El-Sharif 2014). This served the double aim of consolidating the international image of King Abdallah II’s Jordan as an exceptional oasis of peace, prosperity, and progress amid the regional turmoil, and provide domestic legitimation for his parallel unpopular foreign policy realignment with the United States (Ryan 2004). The latter was rewarded by the US with an outstanding amount of yearly aid, which played a pivotal role to both shape and carry out the neoliberal transition of the country, and keep feeding the military and public expenditures (Barari 2015). Also, foreign aid revealed pivotal to further expand and consolidate the process of penetration, cooptation, and directive control of Jordanian civil society inaugurated under King Hussein, whereby the proliferation of CSOs, NGOs, and initiatives addressed to enhance human rights and advocacy, provide aid to disadvantaged social strata, encourage political participation, were turned into yet another instrument of hegemonic incorporation (Tauber 2019). As such, the sharp repressive shift in the state management of political dissent which followed the launch of Jordan First got concealed under a facade of incremental democratization refraining the language of liberal democracy. This process was consistently sustained by the enactment and the strategic application of press restrictions, the latter following a carefully tailored “hit one to educate one hundred” sanctioning logic which aimed to suffocate the international diffusion of any news or contentious event contradicting the official self-narrative of the country. This also included relatively minor episodes of dissent expressing the existence of economic discontent in the country. In 2007, for instance, two reporters from the Egyptian al-Ghad TV were assaulted by security forces as they attempted to cover a bus strike in Amman (Freedom House 2008). As for major events, in 2002 international press was banned from entering the Southern city of Ma’an as a massive military operation sieged the city for days, and two journalists of the Qatari network Al Jazeera were detained for having reported the news (CPJ 2003). Also, allegations of corruption were systemically silenced, and the international coverage of pro-Palestinian or pro-Iraqi demonstrations tightly controlled (Schwendler 2003, 18-23; Greenwood 2003b).

In the medium term, however, neither cooptation and persuasion, nor sanctioning and repression were sufficient to overshadow the growing economic and political discontent for the neoliberal and autocratic policies through which King Abdallah II’s ‘philosophy of governance’ ultimately reified.1 The first site of dissent burgeoned precisely among the historical East Bank rural constituencies of the monarchy, whereby the militarization of welfare and the continuous injection of development funds failed to offer an adequate compensation for the dismantlement of public welfare, the precarization and contraction of public employment, and the booming inflation. Their discontent was also characterized by a certain identity overtone as, following the ethno-national division of labor emerged over the years from the patronizing expansion of the public sector, the implementation of the king’s neoliberal agenda inevitably turned in favor of the Palestinian-dominated, urban private sector (Tell 2015, 6). The second site coincided instead with the political (leftists, Islamists) and those sections of the urban, (possibly Western) educated middle-classes (professional associations, journalists, students) who, after the high hopes for greater democratization rose by King Abdallah II at the beginning of his mandate, got increasingly frustrated by the formal cosmetic openings of the king and his ever-tighter restrictions of the margins of political dissent.

III – 2011 and beyond: King Abdallah II’s new legitimizing tropes

Albeit some incipient signs of distress had begun to emerge already in the second half of the 2000s, until the 2010s Jordanian mounting social dissent remained substantially smoldering (Ababneh 2016). The scenario radically changed from 2010 onwards, as a new wave of privatizations and the dramatic backlashes of the 2008-2009 financial crisis on the Jordanian economy triggered an unprecedented wave of labor unrest (Jordan Labor Watch 2011). The escalation was propelled by the successful mobilizations of the port workers of Aqaba, which unleashed a veritable domino effect storming the private and public sectors alike. Amid this awakening, the military retirees, who had historically represented one of the major loyalist bases of monarchical power, took the field of social opposition and succeeded to coalesce around them a coalition of East Bank nationalists challenging King Abdallah II’s economic policies, power practices, and nationalist discourse at the very heart (Tell 2015). The input for their transgressive activation arrived from the rumors which wanted the project of establishing Jordan as an alternative Palestinian homeland as incumbent (Tell 2015, 5). The mobilization of military veterans intertwined soon with the contentious activation of Islamists and leftist groups in the wake of the Parliamentary elections in November 2010, which likewise put on the forefront of the political confrontation the kingdom’s economic policies, the quest for genuine democratic reforms, and the rampant corruption (Tell 2015). The process further enlarged in 2011, as the revolutionary winds blowing all over the region reached also the eastern shore of the Jordan River.

The early protests started in January in the city of Dhiban, then spread to the rest of the rural East Bank cities, and finally reached the capital. The widening of the protest’s geographical scope coincided with the expansion of the spectrum of mobilized social actors. The most important new actors included tribal leaders and, above all, a new expanding network of youth activists organized in a variety of informal platforms, collectives, and territorial coordination committees in rural and urban areas alike (Yom 2015). The three major political points around which their overall demands converged was the imposition of constitutional curbs on royal power, holding new elections with a more equitable electoral law, and uprooting endemic corruption from state, encompassed in the immediate call for the resignation of the Prime Minister Samir Rifai (Yom 2014, 234). The zenith of this early wave of mobilizations was on March 24, as a coalition of emerging youth activists (the «March 24 Youth») launched a call on social media to permanently occupy the Inner Circle in central Amman. The March 24 initiative was brutally clamped down by the unopposed violent counter-revolutionary incursion of loyalist shabiha (thugs), which prevented the emergence of a permanent site for protest. Also, as the mobilizations progressed, the socio-geographical and generational fractures among the various souls of the movements emerged. Nevertheless, mobilizations continued to be carried out (Yom 2014, 243-47). Between 2011 and the Parliamentary elections of 2013, about 8000 protests took place. A second major peak arrived in November 2012, as the lift of fuel subsidies ignited a new sustained wave of mobilizations (Al-Khalidi 2012).

Albeit the Jordanian Hirak maintained a reformist rather than a revolutionary posture, and a participation rate much lower than in Egypt and Tunisia, the overall demands raised by the array of actors who took the streets posed an unprecedented challenge to the endurance and the legitimacy of King Abdallah II’s rule. The first major challenge came from the dislocation of the younger strata of the historical monarchical East Bank constituencies from the dominant paternalistic structures of patronage which had regulated their relation with the state. This rupture was better epitomized in the slogan “Huquq, la makarim”, (rights, not-payoffs) under which East Bank youth mobilized and framed their demands for socio-economic rights. The latter got therefore disenfranchised from the rent-extraction mechanisms which had previously dominated rural contentious politics to be transposed straight to the terrain of all-encompassing political reforms (Yom 2014, 242-244). The second major one was grounded in the transgressive outcomes that King Abdallah II’s contradictory discursive and power practices ultimately sorted on those segments of urban middle classes that the king had sought to incorporate in his power base, who were now challenging monarchical authority precisely on the terrain of the promised democratic change. Not least important, the Hirak was displaying in the eyes of a global audience the deep hiatus persisting between the image of Jordan carefully crafted and streamed by the monarch and the concrete realities on the ground.

Against this backdrop, the king’s early response was to use the partial accommodation of popular demands as a means to seize the opportunity of the Hirak to refurbish the incorporation mechanisms whereby he had formerly sought to construct his hegemony. The foundations for this operation were already lied on the month of February 2011, through the prompt substitution of PM Rifai with the veteran politician Maaruf Bakhit, whose military background and tribal heritage was intended – as Sam Yom notes – to resonate with the protesters (Yom 2014, 233). This move was followed by the institution of a variety of ad hoc committees charged to carry out the constitutional, electoral, and anti-corruption reforms that the squares were advocating. The most important was the National Dialogue Committee (NDC), a 52-member commission inclusive of representatives of the new opposition, charged to draw the agenda to drive the kingdom towards a fully-fledged constitutional monarchy. The patronization of the discourse on dialogue and reform through the means of committees was paralleled by the attempt to “re-buy” the loyalty of rural areas and the public sector workers by reinstituting subsidies, conceding wage increases, and rising pensions. The funds were once again provided by the US and the Gulf which, fearing a major regional turmoil, rushed to provide donations in order to sustain Jordan’s stability (Josua 2016, 16-18). However, as it became clear soon after that both strategies were falling short from reducing grassroots pressure and incorporate new elites in the monarchical power structure, the inclusionary road was quickly abandoned to revert back to the repressive and exclusionary practices whereby he had formerly sought to underpin the reproduction of his autocratic rule.

As of March 2011, Hirak youth activists began to be systematically arrested, and transgressive demonstrations in both rural and urban areas were violently clamped down (Yom 2014, 235-236). The immediate pretext for this repressive shift was crafted by amending the Law on Public Gatherings to compel demonstrators to ask for a pre-emptive ministerial authorization, which enabled the authorities to strategically sanction any defiant initiative (Freedom House 2013). The apogee was reached during the anti-austerity demonstrations of November 2012 when, on the lines of Ma’an in 2002, security forces used the iron fist against the protesters of Tafilah with the double-scope of quelling the most radical outpost of the mobilization, and possibly acting as a deterrent for future transgressive protests (Paul 2012).

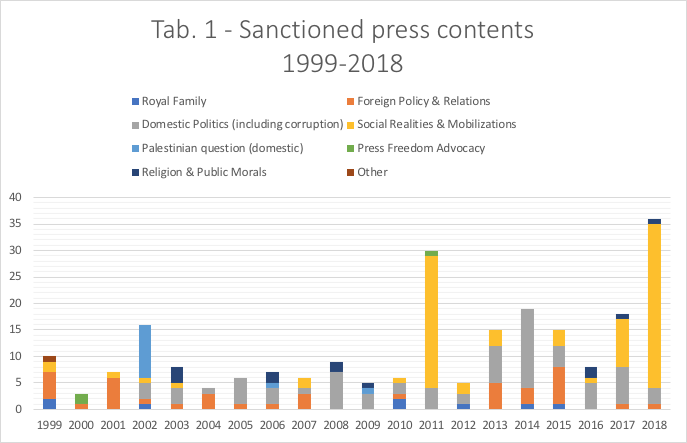

The second main terrain of repression was that of the internet. As the first blogs and online newspapers began to enter the national mediascape in the mid-2000s, the absence of specific constraining legislations against the net created the enabling conditions for the latter to quickly become a comparatively freer and therefore increasingly used alternative source of information and debate. By 2009, more than 50% of Jordanian internet users were estimated to use news websites as the main source of information, with independent outlets such as Ammannews.net or Sarraynews.com occupying the lion’s share (IREX 2009). Equally important, social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter had revealed a fundamental instrument for Hirak activists to organize and stream protest events, launch debates on taboo political issues, and open a branch in the fence of red lines suffocating 1.0 media. The first repressive initiative was enforced in 2012 as an amendment to the Press and Publication Law enshrined the obligation for any website publishing news material concerning “external or internal affairs of the kingdom” to register with the government and to appoint editors-in-chief affiliated to the government-controlled Jordanian Press Association (JPA) (Folio 2015). This triggered the blocking of about 300 websites in 2013 alone, and wielded a permanent Damocles sword above the head of the outlets which managed to be licensed. The initiative was followed by a series of amendments to the Anti-Terrorism and Cybercrime Laws which, by enlarging the sanctionable definition of terrorism and cyber offense to most of the expressive acts sanctioned by the press laws, extended to the whole net the disciplinary operationality of the red lines suffocating traditional media, including comments and personal posts on social media. These amendments de facto stripped online journalists from the prohibition to be detained for the legitimate exercise of profession that the amendments of the Press and Publication Law of 2012 had enshrined (IPI 2015). The results of these initiatives were immediately visible. In 2015, a survey conducted by the Center for Defending the Freedom of Journalists stressed how 95% of Jordanian journalists had arrived to routinely practice self-censorship (CDFJ 2015), and judicial sanctions and gag orders against online journalists and news outlets underwent a steady growth (Cfr. Tab 1).

(Sources: Freedom House, Committee to Protect Journalists, various annual reports)

Eloquently enough, the new restrictions on media freedom started to be fully enforced soon in the aftermath of the January 2013 elections which, albeit having been framed by the king since day one as a fundamental step in the path towards the incremental transition of Jordan to a constitutional monarchy, marked de facto the end of the umpteenth, cosmetic process of defensive democratic opening in the history of the country. This closure was definitively sealed in 2016 by a number of constitutional amendments which entitled the king the exclusive power to appoint the crown prince, the regent, the speaker and members of the senate, the head and members of the constitutional court, the chief justice, the commander of the army, as well as the heads of the General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI) and the Gendarmerie (Abu Rish 2016). Against these blatant democratic setbacks, the legitimizing framing adopted by King Abdallah II was to incorporate in his reformist discourse an overarching campaign of patronizing infantilization of Jordanian society, whereby the latter was systematically portrayed as still too democratically immature – and, hence, still in need to be educated from above to the practices of good citizenship, governance, and “positive” political dialectics – to manage a sudden transition to the fully-fledged constitutional regime that he had wished for his country. The evidences of this immaturity were located in any form of oppositional deviation from the co-opting top-down initiatives identified by the king as sole legitimate pattern of reform, including the boycott of the elections and the participation to the National Dialogue Committee by opposition parties and figures, most notably the Islamic Action Front (King Abdallah II 2012). This infantilization was paralleled by the king’s refurbishing of the Hashemite exceptionalist and stability tropes in the mirror of the repressive response provided by the majority of the regional regimes affected by the Arab Uprisings, and the fitna (military coups, civil strife, rise of Islamic extremism, according to the cases) which followed. These arguments were used respectively as an umpteenth self-attestation of the crown’s alleged intrinsic democratic vocation, and a specter to be constantly evoked to demand domestic loyalty and international support. The blueprint for this discursive recrafting was set up once again in a series of thematic discussion papers published from December 2012 onwards whereby the king, through the language of gradualism and liberal democracy, prepared the terrain to both the postponement sine die of the promised Parliamentary transition, and the legitimization for the further concentration of powers through which his reforms ultimately reified. Within this process, the parallel enforcement of the new restrictions on press and media freedom revealed pivotal to nip in the bud the diffusion and emergence of alternative narratives and debates, restituting to the monarchy monopoly over the representation of the country that the Hirak and the advent of internet had temporarily disrupted.

IV – Neoliberalism, again: Scrutinizing the limits and effectiveness of King Abdallah II’s post-Hirak discourse

Albeit the democratic shortcomings of Jordan’s post-Hirak cosmetic reformism have been stressed and disentangled since day one by a wide array of scholars, activists, and transnational institutions, the discursive strategy of the monarchy managed to exert a certain success. This was particularly the case of King Abdallah II’s international target audience (i.e. Western powers and their liberal elite opinion, most notably the US) (Robin 2019, 224), whose mainstream framing and understanding of Jordan’s post-Hirak regime and political developments came to fully refrain King Abdallah II’s exceptionalist and gradualist tropes. On the onset of 2013 Parliamentary elections, the New York Times, while ascertaining the criticalities of the new electoral law and the unrepresentativeness of the electoral results, framed the event as a great, small step towards the king’s gradual driving of the kingdom towards democracy (Abu Rish 2013). The monarchical discourse on gradualism and democratic immaturity succeeded to exert a certain grip also on consistent strata of the Jordanian population (Martínez 2017). In an opinion survey of 2017, for instance, 92% of respondents declared themselves supporters of gradual political reform, and only 7% declared to trust in political parties (Arab Barometer 2017). These relative successes on the terrain of political reform, however, were not replicated in the making-of quiescent neoliberal subalternities. A first litmus test for this failure arrived in the late spring of 2018, as the project of a new regressive income tax law and a coeval rise in gas prices ignited a week of anti-austerity revolts on a national scale.

Despite the fact that the main triggers of the 2011 Hirak were predominantly rooted in the socio-economic backlashes of Jordanian neoliberal transition and its political implications, the post-Hirak national economic agenda developed in close continuity with that of its recent past. This continuity was partially fostered by the poor macroeconomic performances that the country continued to score, in the shadow of the declining oil prices, and above all, the sharp reduction of tourist incomes, the loss of the Syrian market and the sustained influx of refugees triggered by the regional turmoil. The impact of the crisis was further burdened by the failure of the state to produce decent labor, address youth unemployment, and contain the steady rise in the cost of living. This array of stresses was exacerbated in the first semester of 2018 by the implementation of a new wave of draconian austerity initiatives, as the critical conditions of the national accounts compelled the monarchy to bargain a new conditional loan with the IMF. The anti-austerity revolts began on May 30th and de-escalated on June 7th as, after the resignation of PM al-Mulki on June 4th 2018, the new prime minister Omar al-Razzaz temporarily withdrew the bill. Mobilizing actors included a transversal rural-urban, cross-class coalition of old and new social forces including women, youth, as well as large sections of self-employed, professionals, and white collars which had formerly remained outside from the previous anti-austerity cycles. Equally important, the June mobilization shifted its core grievances straight to the IMF and the neoliberal “politics of impoverishment” systematically pursued by Jordanian lawmakers in the past two decades (Ababneh 2018). This explicitly challenged the monarchical rhetoric outsourcing the roots of the ongoing crisis to the regional economic conjuncture, as well as the equation between neoliberalism, prosperity, and national identity through which the palace had sought to recraft its authoritarian bargain (Ababneh 2018).

Following the post-Hirak draconian contraction of media freedom, until June 4, the tax revolt received barely any mediatic coverage from official Jordanian outlets (Akeed 2018). Also, several journalists were physically prevented from reporting (Freedom House 2018; Freedom House 2019). This silencing from mainstream media was partially counterbalanced by social media which, therefore, managed to lead the mobilization’s narrative within and outside the country. Against this unexpected boomerang effect of state censorship, the regime answered by trying to implement yet another restrictive amendment of the Cybercrime Law. However, the pressures of civil society and activists managed to temporarily make this early attempt fail (Araz 2020)2.

Another major litmus test of the failure of the monarchical discourse to produce quiescent neoliberal subjectivities was represented by the teachers’ strike of 2019. Since the very mobilizations of 2010, Jordanian teachers had represented one of the largest and most active social forces animating the national contentious scenario (Joplin 2021). Their emergence on the forefront of the socio-political arena had walked in parallel with a broader process of contentious re-organization outside of the existing state co-opted union bodies engaged by a variety of public sector workers at the end of the 2000s, as a reaction to the former’s failure to provide adequate answers to the sharp degradation of their labor and living conditions triggered by King Abdallah II’s first decade of neoliberal policies (Adley 2012). The reorganization culminated in 2011 with the successful struggle to obtain the formal recognition of the independent Jordanian Teachers’ Association (JTA), which became henceforth the main representative body of the about 100 000 teachers active in public education. Along with actively participating in the major collective contentious cycles of the decade, one of the main struggles of the JTA was that of salaries. The question earned a renewed priority in the aftermath of post-2016 austerity, as the combination between new taxes and rising cost of living reduced the purchasing power of their salaries to the edges of the estimated relative poverty line (Nusairat 2019). In 2014 the JPA had already staged a two-week strike to demand the adequation of their salaries to the inflation rate. According to the JPA, the strike was interrupted after reaching an informal agreement with the government whereby the latter committed to deliver a 50% rise by maximum 2019 (7iber 2019). As the promise remained a dead letter, in May 2019 the JPA started to send a number of solicits to the cabinet demanding to honor its former commitment. The government counter-answered by binding the demanded 50% rise to a broader project of neoliberal restructuring of the educational sector conditioning the withdrawal of bonuses to teachers’ performances. The last drop in the cup arrived on September 5, as a disproportionate police operation violently disrupted a peaceful sit-in that teachers were staging in central Amman. This pushed the teachers to call for an open-ended strike until the full satisfaction of their demands were met, including formal apologies for the September 5 repression. The strike began on September 8 and concluded on October 6, when, after one month of relentless bargaining, the government ultimately endorsed teachers’ demands.

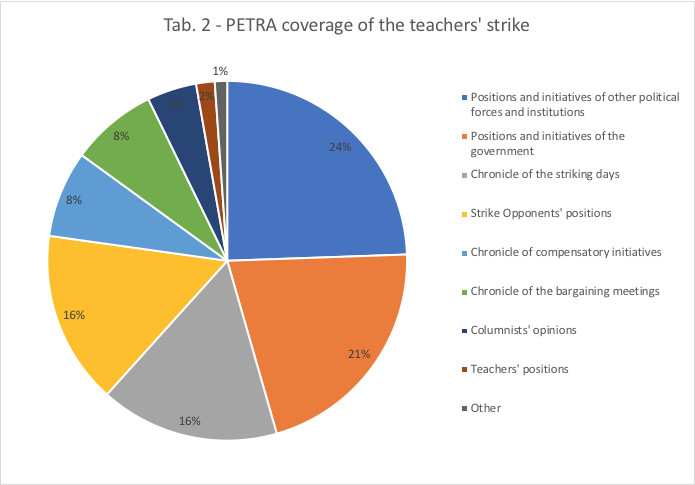

Albeit the strike never transcended the boundaries of its constituency and specific agenda, the government looked at its development with great preoccupation. The first source of concern was related to the possibility, in case of success, of a domino effect to other workers groups, most notably in the public sector, whereby the treasury would have lacked adequate financial coverage. The second one was related to the wide popular support that the strike earned across social classes and geographical areas (Jarar and Ali 2019), in a moment when the socio-economic tensions were still far from being defused. Between February and March 2019, for instance, hundreds of young unemployed from deprived rural areas staged marches towards the capital to demand job opportunities (al-Sharif 2019). More broadly, since the month of January 2019, at least 62 collective actions related to the quest for the access to socio-economic rights have been recorded (Lebanon Support, Mapping of Jordan). Against this backdrop, the early strategy of the government was to resume the old card of the patronizing dialogue, whereby it sought to impose its own solution to the dispute by leveraging on teachers’ sense of loyalty to the homeland in the mirror of its financial difficulties3 This was paralleled by a massive campaign of lateral delegitimation of the teachers through the stigmatization of the strike, by framing it as a blatant constitutional and ethical violation of the sacred right of students to access education. The realization of this double-operation found a crucial executive weapon in the renewed resonance guaranteed to the government hegemonic discourse by the new restrictions on media freedom, most notably via the concentration of the main bulk of the coverage of domestic affairs in the hands of the state news agency PETRA (Al-Khudari, Al-Quraan and Al-Zoubi 2021). The latter, this time, was used since day one as a counterbalance from above to the narratives spread by the teachers and their sympathizers through social media. As the content analysis summarized in Tab. 2 shows, out of 147 entries dedicated by PETRA to the teachers’ strike, only 2% reported the positions of JTA, against an astonishing 85% dedicated to directly refrain (21%) or corroborate the government hegemonic discourse and its strategic framings (64%). The latter was made of the political positions of other major political forces and institutions (24%), the positions of the social forces (16%) and the initiatives (8%) hostile or compensatory of the strike, and a deeply biased chronicle of the striking days (18%), whose bulk of content predominantly focused on the problems and the distress that it produced. This pro-government bias was also largely reflected in the coverage provided by the most important national mainstream media (press, information websites) which, as stressed by a study of the Committee to Defend the Freedom of Journalist, was characterized by a very low degree of plurality of opinions, and an over-reliance of the coverage (70%) on duplicated material depending on institutional sources (CDFJ 2019).

(Content analysis of the Jordanian News Agency PETRA website)

Despite these consistent efforts, by the eve of the third week, neither the teachers’ position, nor their popular support showed signs of distress. This pushed the government to opt for more muscular techniques, starting from the threat of mass dismissals in case the strike would not be immediately revoked. However, as the initiative sparked further outrage, it became clear that to prevent an escalation, a full and formal endorsement of teachers’ demands was inevitable.

Conclusion

As Pierre Bourdieu points out, one of the basic preconditions which enable the performative effectiveness of a political discourse relies on the degree of adherence of the pre-visions that it fosters to the knowledge of the social world shared by the subjects upon which it seeks to exert influence (Bourdieu 1981).

As our analytical excursus has attempted to demonstrate, since the very ascension of King Abdallah II to the throne, restrictions on media freedom and their executive applications have been engineered and strategized to work as an overarching disciplinary dispositive guaranteeing to the throne, through the means of coercion and amplification, a tight directive control over the country’s narratives. Against the challenge impressed to the reproduction of King Abdallah II’s hegemonic discourse by the Hirak and its aftermaths, the gradualist and stability tropes whereby the king sought to legitimize his umpteenth autocratic re-entrenchment managed to earn adherence in the eyes of his target international audience. The combination between the concrete realities on the ground (growing regional chaos, limited reformist openings, limited influence and audience of political parties) and the coercive silencing of challenging counternarratives, provided the minimal empirical conditions to endow his pre-visions with a performative likelihood. The same can be also said for the grip that the discourses on gradualism and political parties succeeded to exercise on the domestic audience. On the other hand, the lived experience of impoverishment and precarization triggered by two decades of neoliberal policies, continues to pose a major obstacle to the crafting of quiescent neoliberal subalternities, despite the unprecedented occupation of the discursive space reached by King Abdallah II through the means of cumulative restrictions on press and media freedom.

Against the failure of persuasion, in the past year and a half, the Jordanian regime has made an increasing recourse to coercion to clamp down on social dissent (HRW 2021). The opportunity for this repressive shift has been provided by the COVID-19 outbreak, which has offered the legitimizing framework for the regime to declare the state of emergency, and hence to sharply tighten the space for social and political opposition. In July 2020, these restrictions on demonstrations were exploited to raid and shutter the branches of the Jordanian Teachers’ Association all over the national territory and arrest several leaders (HRW 2020a). This tightening has walked in parallel with the implementation of ad hoc gag orders to forbid media coverage of the numerous repressive initiatives engaged by the government against opposition actors and transgressive social mobilizations, as well as the very independent coverage of the state management of the pandemic (HRW 2020b). However, the physiological decline in the number of mobilizations notwithstanding due to the protracted sanitary lockdowns, these repressive initiatives have failed so far to produce a demobilization directly proportional to the state repressive efforts (Lebanon Support, Mapping). Furthermore, the rise in media censorship has started to receive increasing attention from international media and observers (Kingsley, Sweis and Schmit 2021). It is therefore arguable that, in absence of sustained political and economic reforms on more equal and inclusive bases, repression and censorship alone will fall short of guaranteeing to the Jordanian regime the social quiescence and the international validation which, in the past decades, contributed to enabling its reproduction.

Bibliography

7iber. 2019. “لماذا يعتصم معلمو ومعلمات الأردن؟ “, 7iber, September 05, 2019. https://www.7iber.com/politics-economics/لماذا-يعتصم-معلمو-ومعلمات-الأردن/

Ababneh, Sara. 2016. “Troubling the Political: Women in the Jordanian Day-Waged Labor Movement.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 48, no. 1 (Feb): 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743815001488.

———. 2018. “‘Do You Know Who Governs Us? The Damned Monetary Fund,’”. MERIP Blog, June 30, 2018. https://merip.org/2018/06/do-you-know-who-governs-us-the-damned-monetary...

Abu Rish, Ziad. 2013. “Romancing the Throne: The New York Times and The Endorsement of Authoritarianism in Jordan.” Jadaliyya – جدلية, February 03, 2013. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/27961.

———. 2016. “The Facade of Jordanian Reform: A Brief History of the Constitution.” Jadaliyya – جدلية, May 31, 2016. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/33315

Adley, Fida. 2012. “The Emergence of a New Labor Movement in Jordan,” MERIP 264, (Fall 2012). https://merip.org/2012/08/the-emergence-of-a-new-labor-movement-in-jordan/.

Akeed. 2018. “Official Media Absent; Facebook Leading Protests,” Akeed, April 06, 2021. http://www.akeed.jo/en/post/1742/Official_Media_Absent_Facebook_Leading_....

Al-Khalidi, Suleiman. 2012. “Jordan lifts fuel subsidies, sparks protests”, Reuters, November 13, 2012. https://www.reuters.com/article/jordan-gasoline-prices-idUSL5E8MDCKK2012...

Al-Khudari, Majid Numan, Al-Quraan Muhamad I., and Al-Zoubi Ashraf Faleh. 2021. “The Reliance of the Jordanian Daily Newspapers on the Jordan News Agency as the Main Source of News and Its Impact on Content.” Psychology and Education Journal 58, no. 2 (Feb): 4776–90. https://doi.org/10.17762/pae.v58i2.2869.

Al-Sharif, Omar. 2019. “Hundreds of Jordanians march toward capital demanding jobs”. Al-Monitor, March 5, 2019. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2019/03/jordan-youth-march-sit-in-r...

Alnajjar, Abeer. 2021. “What's wrong with Jordanian media?”. OpenDemocracy, April 9, 2021. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/whats-wrong-jord...

Andoni, Lamis, and Jillian Schwedler. 1996. “Bread Riots in Jordan.” Middle East Report, no. 201 (Winter): 40–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3012771.

Arab Barometer. 2017. “Jordan Five Years After the Arab Uprisings”, Arab Barometer, August 1, 2017. https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/Jordan_Public_Opinion_S...

Araz, Sevan. 2020. “Jordan adopts sweeping cybersecurity legislation”. Middle East Institute, January 30, 2020. https://www.mei.edu/publications/jordan-adopts-sweeping-cybersecurity-le...

Barari, Hassan A. 2015. “The Persistence of Autocracy: Jordan, Morocco and the Gulf.” Middle East Critique 24, no. 1 (Jan): 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2014.1000084.

Baylouny, Anne Marie. 2008. “Militarizing Welfare: Neo-Liberalism and Jordanian Policy.” Middle East Journal 62, no. 2 (Spring): 277–303.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1981. “Décrire et prescrire.” Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 38, no. 1: 69–73. https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1981.2120.

CDFJ. 2019. “الحياد الغائب في تغطية إضراب المعلمين في وسائل الإعلام”, Committee to Defend the Freedom of Journalists, Septemebr 2019. https://cdfj.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%...

CPJ. 2003. Attacks on the Press 2002: Jordan. Committee to Protect Journalists, March 31, 2003. https://cpj.org/2003/03/attacks-on-the-press-2002-jordan/

El-Sharif, Ahmad. 2014. “Constructing the Hashemite Self-Identity in King Abdullah II’s Discourse.” International Journal of Linguistics 6, no. 1 (Feb): 34–52. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v6i1.5170.

Folio, Ryan. 2015. “The 2012 Amendment to Jordan’s Press and Publications Law: The Jordanian Government’s Stigmatization Campaign against News Websites.” Jadaliyya – جدلية, December 19, 2015. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/32794.

Freedom House. 2008. Freedom of the Press 2008 - Jordan, 29 April 2008, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/4871f610c.html

———. 2013. Freedom in the World 2013 - Jordan, 23 April 2013, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5180c904a.htm

———. 2018. Freedom on the Net 2018 – Jordan, November 1, 2018, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5be16b0dc.html;

———. 2019. Jordan: Freedom on the Net 2019 Country Report, Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/country/jordan/freedom-net/2019

Greenwood, Scott. 2003a. “Jordan’s ‘New Bargain:’ The Political Economy of Regime Security.” Middle East Journal 57, no. 2 (Spring): 248–68.

———. 2003b. “Jordan, the al-Aqsa Intifada and America’s ‘War on Terror’”, Middle East Policy 10, n°3: 90-111

Sakr, Naomi. 2013. ‘We Cannot Let it Loose’: Geopolitics, Security and Reforms in Jordanian Broadcasting” in Tourya Guaaybess (ed.), National Broadcasting and State Policy in Arab Countries. Palgrave Macmillan. 96-116

HRW. 2021. “World Report 2021: Jordan”. Human Rights Watch, https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2021/country-chapters/jordan

———. 2020a. “Jordan: Teachers’ Syndicate Closed; Leaders Arrested”. Human Rights Watch, July 30, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/07/30/jordan-teachers-syndicate-closed-lea...

———. 2020b. “Jordan: Escalating Repression of Journalists”. Human Rights Watch, August 18, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/08/18/jordan-escalating-repression-journal...

ICNL. 2019. “The Right to Freedom of Expression Online in Jordan”, International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, May 2019, 10 https://www.icnl.org/wp-content/uploads/Guide-to-Internet-freedoms-in-Jo...

IREX. 2009. “Media Sustainability Index 2009 – Jordan”, available at: https://www.irex.org/sites/default/files/pdf/media-sustainability-index-...

IPI. 2015. “Jordan’s Online Media Freedom at Stake,” International Press Institute, November 19, 2015, https://ipi.media/jordans-online-media-freedom-at-stake/

İşleyen, Beste, and Nadine Kreitmeyr. 2021. “‘Authoritarian Neoliberalism’ and Youth Empowerment in Jordan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 15, no. 2 (Mar): 244–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2020.1812996.

Jones, Adam. 2002. “From Vanguard to Vanquished? The Tabloid Press in Jordan.” Political Communication 19, no. 2 (Apr): 171–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600252907434.

———. 1998. “Jordan: Press, Regime, and Society Since 1989”. Montréal : Consortium Universitaire pour les Études Arabes.

Marshall, Shana. 2013. “Jordan’s Military-Industrial Complex and the Middle East’s New Model Army,”. MERIP. https://merip.org/2013/06/jordans-military-industrial-complex-and-the-mi....

Jarar, Shaker and Ali Doa, “إضراب من أجل الصالح العام”, 7iber, September 14, 2019. https://www.7iber.com/politics-economics/إضراب-من-أجل-الصالح-العام/.

Jordan Labor Watch. 2011. “Labor Protests in Jordan 2010”. Report Series, Issue 1/2011, February 2011. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/amman/10104.pdf

Joplin, Ty. “Jordanian Teachers Union Leaves Behind Legacy of Wins”, Labor Notes, May 03, 2021. https://labornotes.org/blogs/2021/05/learning-jordans-militant-teachers-...

Josua, Maria. 2016. “If You Can’t Include Them, Exclude Them: Countering the Arab Uprisings in Algeria and Jordan.” GIGA Working Papers 258 – 05/2016. https://pure.giga-hamburg.de/ws/files/21197835/wp286_josua.pdf

King Abdallah II. 2002. “Letter to Ali Abul Ragheb on the national interest”, October 30, 2002. https://kingabdullah.jo/en/letters/letter-ali-abul-ragheb-national-interest

———. 2012. “Our Journey to Forge Our Path Towards Democracy”, Discussion Paper, December 29, 2012. https://kingabdullah.jo/en/discussion-papers/our-journey-forge-our-path-...

Kingsley, Patrick, Rana F. Sweis and Eric Schmitt. 2021. “Royal Rivalry Bares Social Tensions Behind Jordan’s Stable Veneer”. The New York Times, April 10, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/10/world/middleeast/jordan-king-crown-pr....

Kreitmeyr, Nadine. 2019. “Neoliberal Co-Optation and Authoritarian Renewal: Social Entrepreneurship Networks in Jordan and Morocco.” Globalizations 16, no. 3 (Apr): 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1502492.

Lebanon Support. 2021. “Mapping of Collective Actions in Jordan”. https://civilsociety-centre.org/cap/collective-actions-mapping-jordan

Lucas, Russell. 2003. “Press Laws as a Survival Strategy in Jordan, 1989–99.” Middle Eastern Studies, no 4 (Oct): 81-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263200412331301797.

Martínez, José Ciro. 2017. “Jordan’s Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: The Production of Feeble Political Parties and the Perceived Perils of Democracy.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 44, no. 3 (Jul): 356–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2016.1193805.

Najjar, Orayb Aref. 1998. “The Ebb and Flow of the Liberalization of the Jordanian Press: 1985–1997.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 75, no. 1 (Mar): 127–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909807500113.

Nusairat, Tuqa. 2019. “Teachers’ Protest Challenges Jordanian Status Quo,” Atlantic Council, September 27, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/teachers-protest-challe...

Oudat, Mohammed Ali Al, and Ayman Alshboul. 2010. “‘Jordan First’: Tribalism, Nationalism and Legitimacy of Power in Jordan.” Intellectual Discourse 18, no. 1 (Jun): 65-96

Paul, Katie. 2012. “In Jordan's Tafilah, Demands Escalate for King’s Downfall”. Al-Monitor, November 16, 2012. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2012/al-monitor/jordan-king-talifah...

Phillips, Colfax, 2019. “Dhiban as Barometer of Jordan’s Rural Discontent,” MERIP 292, n°3 (Fall-Winter) https://merip.org/2019/12/dhiban-as-barometer-of-jordans-rural-disconten...

Robins, Philip. 2019. A History of Jordan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Robinson, Glenn E. 1998. “Defensive Democratization in Jordan.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 30, no. 3 (Aug): 387–410.

RSF. 2021. Reporters Without Borders - “Jordan”. Reporters Without Borders https://rsf.org/en/jordan

Ryan, Curtis R. 2004. “‘Jordan First’: Jordan’s Inter-Arab Relations and Foreign Policy Under King Abdullah II.” Arab Studies Quarterly 26, no. 3 (Summer): 43–62.

———. 1998. “Peace, Bread and Riots: Jordan and the International Monetary Fund.” Middle East Policy 6, no. 2 (Oct): 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4967.1998.tb00308.x.

Rugh, William A. 1979. The Arab Press: News Media and Political Process in the Arab World. New York: Syracuse University Press

Schwedler, Jillian. “More Than a Mob: The Dynamics of Political Demonstrations in Jordan.” Middle East Report, no. 226 (Spring): 18–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/1559278.

———. 2002. “Occupied Maan,” MERIP Blog, March, 12, 2002 https://merip.org/2002/12/occupied-maan/.

Tauber, Lilian. 2019. ‘Social entrepreneurship, civil society, and foreign aid in Jordan’ in Natil, Ibrahim, Chiara Pierobon, and Lilian Tauber, (eds). The Power of Civil Society in the Middle East and North Africa: Peace-Building, Change, and Development. London: Routledge https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429265006.

Tell, Tariq. 2015. “Early Spring in Jordan: The Revolt of the Military Veterans.” Carnegie Middle East Center. https://carnegie-mec.org/2015/11/04/early-spring-in-jordan-revolt-of-mil...

Tweissi, Basim. 2019. “Media Reform in Jordan: Severe Transformations.” Confluences Méditerranée 110, no. 3: 113–26. https://doi.org/10.3917/come.110.0113.

———. 2021. ‘Jordan: Media’s Sustainability during Hard Times’ in Kozman Caludia and Carola Richter (eds.). Arab Media Systems. Open Book Publishers: 55-71 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0238.

Yom, Sean L. 2015. “The New Landscape of Jordanian Politics: Social Opposition, Fiscal Crisis, and the Arab Spring.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 42, no. 3 (Jul): 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/13530194.2014.932271.

———. 2014. “Tribal Politics in Contemporary Jordan: The Case of the Hirak Movement.” Middle East Journal 68, no. 2 (Spring): 229–47.

———. 2009. “Jordan: Ten More Years of Autocracy.” Journal of Democracy no. 4 (Oct): 151–66. https://www.journalofdemocracy.com/articles/jordan-ten-more-years-of-aut....

Younes, Ali. 2020. “Jordan imposes state of emergency to curb coronavirus pandemic”. Al-Jazeera, March 17, 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/3/17/jordan-imposes-state-of-emergen...

- 1. The complete series of King Abdallah II’s discussion papers is available on his official website at the following address: https://kingabdullah.jo/en/vision/discussion-papers.

- 2. After years of struggle, the Jordanian government will ultimately manage to amend the Cybercrime Law on January 2020 (Araz 2020)

- 3. https://petra.gov.jo/Include/InnerPage.jsp?ID=112104&lang=ar&name=news

Dr. Rossana Tufaro is a Research Fellow and a researcher in Contentious Politics - MENA at the Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action, with a focus on Lebanon and Jordan. In the past years, she devoted most of her research activities to the investigation of Lebanese labor history and the history of Lebanese popular politics in the global 1960s from a transnational perspective. Her main research interests include the history of popular and contentious politics in the Levantine region, the political economy of the MENA region, and the history of transnational radical cultures in the Mediterranean area. Over the years, she has lectured in a variety of international conferences and universities, and has been affiliated with numerous Lebanese and Italian academic institutions. Rossana is currently a teaching Assistant of Contemporary History of the Arab Middle East at the University of Rome “La Sapienza”. Rossana has a PhD in Studies on Africa and Asia, she specialised in the social and political history of contemporary Lebanon.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6814-8736

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/rossana.tuf/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/rossana_tuf