Social Spending in Lebanon: A Fallacy of State Welfare

This article lays out three critical examples that capture distinct ways in which public finance is wasted through different forms of policy maneuvers and political practices, resulting in what could be labeled as “false protection.” It shows how policy tools have been politicized by the elite, unfortunately backed by traditional media, to consolidate their grip on the state apparatus, and ultimately to maintain their sectarian loyalty system and deep-rooted patronage networks.

To cite this paper: Iskandar Boustany,"Social Spending in Lebanon: A Fallacy of State Welfare", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2026-02-01 00:00:00. doi:

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/ar/paper/social-spending-lebanon-fallacy-state-welfare

Beyond the multi-faceted crisis narrative and macro-financial developments, Lebanon has historically managed to “defy gravity”[1], and strike a balance between two conflicting dynamics. While the country champions a political framework of a liberal economic model[2], its people demand an extended welfare state. In this short article, I attempt to explore how policies and practices have led, not only, to the emergence of lower and lower middle-classes, but also a seemingly contradiction: a deep mistrust towards the state and its shortcomings, while helplessly asking the famous question “Where is the state” (wayniyeh al-dawleh)?

More State and Less Welfare

Historical data reveal divergent trajectories between fiscal inputs and public service outputs, without even the need to examine policy outcomes. This article lays out three critical examples that capture distinct ways in which public finance is wasted through different forms of policy maneuvers and political practices, resulting in what could be labeled as “false protection.” It shows how policy tools have been politicized by the elite, unfortunately backed by traditional media, to consolidate their grip on the state apparatus, and ultimately to maintain their sectarian loyalty system and deep-rooted patronage networks. The first example unveils how subsidies, particularly electricity subsidies, can be engineered and reengineered to capture public money while the economy was experiencing a critical drought of foreign reserves; the second example shows how spending levels in public education mask a critical diversion away from the initial policy purpose in a country extensively relying on human capital; and the third example explains how deliberate policy inaction can systemize exclusion and disengagement and seriously compromise shaky social protection systems.

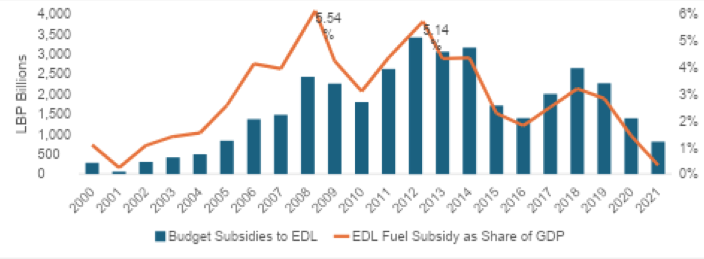

The Illusion and the Anatomy of Electricity Subsidies

Over two decades of pegged tariffs contributed to exposing the state treasury to global oil price fluctuation, covering up for significant technical and non-technical losses[3], consuming up to 5% of GDP (Figure 1), and the build-up of an unsustainable stock of national debt. A cumulative subsidy price tag exceeding USD 23 billion in direct treasury transfers, probably sufficient to finance the establishment of more than 40 new power plants[4] and to bridge the annual production gaps estimated today between 1300 and 2000 MW[5].

Beyond the production, transmission, and financing controversies that predominated the public debate, three critical anomalies were fully weaponized to manipulate public opinion and sentiments, and ultimately to feed crony capitalism[6].

1. High regressivity, meaning that the people who are most in need of subsidy support are those who benefit the least.

2. The subsidy architecture across the value chain was positioned at the import stage, giving a high leverage for two categories of market agents: (i) the large importers and wholesale distributors who were able to suck the subsidy prime, particularly during the crisis, exacerbating regular shortages, and inflicting further regressive currency devaluation[7]; (ii) the private generator owners who were able to artificially reduce their operational costs and position themselves for decades as the only expensive alternative, making millions of unjustified and untaxed profits.

3. The subsidy was used as a tool of policy manipulation to maintain the status quo. The system utilised mainstream media to instill a fear of subsidy lift, portrayed by many as a “catastrophe.”[8] It somehow contributed to the build-up of a certain level of social acceptance that gave the political elite a policy maneuver to oscillate between fiscal and monetary subsidies. Unfortunately, the monetary subsidy provided a safe haven for money diversion and corruption, shielded behind the complexity of the monetary policy and the secretive nature of BDL operations.

Figure 1: Transfers to EDL to Cover the Purchase of Oil

Source: Public Finance Monitor, 2020-2021

Remark: 2021 subsidy level excludes the monetary subsidy financed by BDL reserves

The Contradiction of Public Education

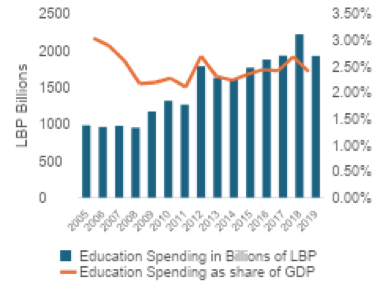

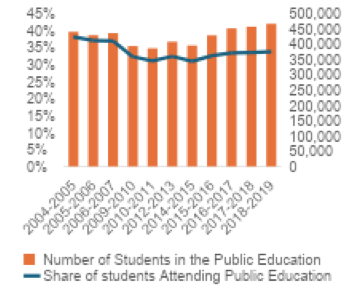

Over three decades, public education has deviated from being a decent alternative[9] to become a last resort for teachers. Close observation of fiscal and programmatic data, queried from multiple official sources (Figures 2 and 3), reveals multiple worrying patterns:

1. More public spending on education and fewer enrollments in public education. While the issue of public-school teachers' rights and employment status was extensively portrayed as the major challenge in the public education sector, the official debate has overlooked the input-output widening mismatch between resources invested and improvement of the services (quality of education, increased enrolment levels, etc.). In a comparable timeframe, data show that nominal spending on education has increased steadily. It doubled between 2005 (LBP 983 billion) and 2019 (LBP 1,925 billion), while the total enrollment variation between the same time period did not exceed 5%.

2. Unjustified public spending on private education. The totals showcased in the graph below include state financing of non-profit private schools, which is a key element of the education sector. However, it also includes public spending as social benefits to public employees to enroll their children in private schools. Between 2004 and 2021, the state spent a cumulative amount of LBP 3373 billion (equivalent to more than USD 2 billion) diverted away from public education, and unfortunately, this gave a worrying signal that state employees had completely lost trust in the public service provided by the state itself.

3. The public education sector is critically overstaffed. On a macro scale, the wages and salaries of education personnel averaged around 21% of the total wage bill, surpassing civilian personnel. On a microscale, public schools recruit one teacher (all contractual statuses included) for every 7.3[10] students[11] compared to 13[12] students on average in private schools.

Figure 2: Public Spending on Education (2005-2019)

Sources: PFM reports 2005-2017 and CBD 2017-2019

Remark: Spending totals include MEHE budget and school allowances, while excluding MoSA spending on Education for PWD

Figure 3: Enrollment in Public Education (2004/05-2018-19)

Source: CRDP Statistics

Remark: Totals include general education, TVET, and higher education. Years with data gaps were omitted.

From Exclusionary Coverage to Exclusionary Paradigm in Social Protection

Before the crisis, state-financed social protection schemes, estimated at USD 2.2 billion (4% of GDP) in 2018 and 2019[13], were criticized for limited and skewed beneficiary coverage, for inflicting heavy burdens on public finance, and for being excessively generous[14] for a few. Only 2% of the population directly benefited from those schemes, and a significant part of the public sector was systematically excluded, notably contractual and hourly workers. Public pensions (including the pension scheme and end-of-service indemnities) constituted the second-largest spending item in the budget, and technically a key fiscal constraint for adjusting the salary scale.

Unfortunately, the crisis brought in another dimension of critical exclusion: a brutal shift from scattered contributory schemes[15] to non-contributory schemes, and a deepening of the reliance on donor financing. The latter typically centers on targeted interventions that rely on highly contested[16] ad hoc targeting mechanisms. This shift has further exposed vulnerable populations to the risks of donor fatigue, while sustaining the illusion of state intervention. In reality, the public, and particularly middle and high-income earners, has long grown accustomed to minimal contributions which reinforce systemic inequities. Ultimately, this shift delivered the fatal blow to what remained of Lebanon’s social contract.

Mission Impossible … is Technically Possible

Away from the dilemma of political tensions and disagreements in the country, redirecting social spending on the right track requires, first and foremost, a complex yet achievable budget reform that helps the state transition from input-based year-to-year replication to output/outcome-based planning. In simpler words, adopting an integrated program-based budget requires an upstream overhaul: ministries must redesign their internal structures around integrated programs rather than administrative silos, develop performance indicators, and include monitoring systems into their workflows. When budgets are structured around tangible programs with measurable goals, they become comprehensive and accessible to all stakeholders and eventually a tool for better planning. This constitutes an essential pillar of democratic accountability by making cause-and-effect visible and by structurally linking between policy and program objectives on one hand and spending allocations on the other hand. Over time, it will contribute to fostering a culture where fiscal transparency isn’t just a compliance exercise but a tool for developing better public policies and services.

List of References

CDR (Council for Development and Reconstruction). 2013. Social Infrastructure.Accessed December 10, 2025.

http://data.infopro.com.lb/file/educationreportCDR.pdf

Chehayeb, Kareem. 2021. “Catastrophe” warning as Lebanese officials lift fuel subsidies”. Al Jazeera. Published June 28, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/28/catastrophe-warning-as-lebanese-officials-lift-fuel-subsidies

Centre for Educational Research and Development (CRDP). Statistical Bulletin 2023–2024. Beirut: CRDP, 2024.

https://www.crdp.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/Statistical%20Bulletin%202023-2024.pdf

Électricité du Liban (EDL). 2022. Lebanon Electricity Sector Cost Recovery Plan. Accessed December 11, 2025. http://www.edl.gov.lb/Lebanon%20Electricity%20Sector%20Cost%20Recovery%20Plan.pdf

Hariri, Nizar. 2025. Subsidizing Without Protection: The Lebanese health sector in focus. CNRS-ANR. Unpublished manuscript.

Hariri Nizar, Boustany Iskandar. 2025. Can a National Unified Registry in Lebanon Constitute a Step Towards Universal Social Protection? A Comprehensive Technical Report. Beirut: The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action. Published April 3, 2025. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/national-unified-registry-lebanon-step-towards-universal-social-protection

Human Rights Watch. 2023. “Cut Off From Life Itself: Lebanon’s Failure on the Right to Electricity.” March 9, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/03/09/cut-life-itself/lebanons-failure-right-electricity

Diwan Ishac, Adeel Malik, and Izak Atiyas. 2019. Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring. Oxford University Press.

Laughlin Samer, Ali Ray, and Dalia Wood. 2025. Fuelling Addiction: How Importers And Politicians Keep Lebanon Hooked On Oil. The Badil. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://thebadil.com/investigations/fuelling-addiction-how-importers-and-politicians-keep-lebanon-hooked-on-oil/

Demarco, Gustavo. 2013. Retirement Pensions: What options for Lebanon? Paper presented at the International Symposium on The Future of Retirement in Lebanon, April 29, 2013.

Institute of Finance Lebanon. 2025. Review of the Government Spending on Social Protection in Lebanon. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/sites/default/files/2025-11/Report-Review%20of%20Government%20Spending%20on%20Social%20Protection-Nov25-EN.pdf

Scala, Michele. 2022. An Intersectional Perspective on Social (In) Security. Making the Case for Universal Social Protection in Lebanon. Beirut: The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action. doi.org/10.28943/cskc.003.00046

The World Bank Group. 2019. So When Gravity Beckons, the Poor Don’t Fall: Lebanon Economic Monitor Washington, DC: World Bank.

This is Beirut. 2025. “The Electricity Challenge in Lebanon.” Accessed December 10, 2025. https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/articles/1319827/the-electricity-challenge-in-lebanon

[1] World Bank Group. 2019. So When Gravity Beckons, the Poor Don’t Fall: Lebanon Economic Monitor. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/349901579899850508/pdf/Lebanon-Economic-Monitor-So-When-Gravity-Beckons-the-Poor-Dont-Fall.pdf

[2] Hariri, Nizar. 2025. Subsidizing Without Protection: The Lebanese Health Sector in Focus. CNRS-ANR. Unpublished manuscript.

[3] Électricité du Liban (EDL). 2022. Lebanon Electricity Sector Cost Recovery Plan. Accessed December 11, 2025. http://www.edl.gov.lb/Lebanon%20Electricity%20Sector%20Cost%20Recovery%20Plan.pdf

[4] Human Rights Watch. 2023. “Cut Off from Life Itself”: Lebanon’s Failure on the Right to Electricity. March 9, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/03/09/cut-life-itself/lebanons-failure-right-electricity

[5] This is Beirut. 2025. “The Electricity Challenge in Lebanon.” Accessed December 10, 2025. https://thisisbeirut.com.lb/articles/1319827/the-electricity-challenge-in-lebanon

[6] Diwan, Ishac, Adeel Malik, and Izak Atiyas. 2019. Crony Capitalism in the Middle East: Business and Politics from Liberalization to the Arab Spring. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[7] Laughlin Samer, Ali Ray, and Dalia Wood. 2025. “Fuelling Addiction: How Importers and Politicians Keep Lebanon Hooked on Oil.” The Badil. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://thebadil.com/investigations/fuelling-addiction-how-importers-and-politicians-keep-lebanon-hooked-on-oil/

[8] Chehayeb, Kareem. 2021. “Catastrophe Warning as Lebanese Officials Lift Fuel Subsidies.” Al Jazeera, June 28, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/28/catastrophe-warning-as-lebanese-officials-lift-fuel-subsidies

[9] CDR (Council for Development and Reconstruction). 2013. Social Infrastructure. Accessed December 10, 2025. http://data.infopro.com.lb/file/educationreportCDR.pdf

[10] (277,216) students in public schools are covered by 37,841 teachers.

[11]Centre for Educational Research and Development (CRDP). Statistical Bulletin 2023–2024. Beirut: CRDP, 2024. https://www.crdp.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/Statistical%20Bulletin%202023-2024.pdf

[12] 645,879 students in private schools are covered by 49,992 teachers.

[13] Institute of Finance, Lebanon. 2025. Review of the Government Spending on Social Protection in Lebanon. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://www.institutdesfinances.gov.lb/sites/default/files/2025-11/Report-Review%20of%20Government%20Spending%20on%20Social%20Protection-Nov25-EN.pdf

[14] Demarco, Gustavo. 2013.Retirement Pensions: What options for Lebanon? Paper presented at the International Symposium on The Future of Retirement in Lebanon, April 29, 2013.

[15] Scala Michele. 2022. An Intersectional Perspective on Social (In)Security. Making the Case for Universal Social Protection in Lebanon. Beirut: The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action, 2022. doi.org/10.28943/cskc.003.00046

[16] Hariri Nizar, Boustany Iskandar. 2025. Can a National Unified Registry in Lebanon Constitute a Step Towards Universal Social Protection? A Comprehensive Technical Report. Beirut: The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action. Published April 3, 2025. Accessed December 10, 2025. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/national-unified-registry-lebanon-step-towards-universal-social-protection

Economist - خبير اقتصادي