Recovery in Post-Conflict Tripoli: Towards a Reconceptualization of Conflict, Peacebuilding, and Development in Tripoli, Lebanon

Since the end of the Lebanese Civil War, Tripoli has endured one of the highest densities and frequencies of violent conflict and the highest levels of poverty in Lebanon. Despite its status as Lebanon’s second largest and most impoverished city, the relationship between Tripoli’s protracted conflict and underdevelopment is under-researched. To highlight and address this gap, this paper situates Tripoli’s conflict context within existing scholarly approaches to violence, conflict, and development in divided societies. To do so, it draws upon nine interviews with practitioners working in Tripolitan civil society organizations at the nexus of peace, conflict, and development. This paper argues that the structural social, political, and economic factors that uphold the present state of “de-development” pose major challenges to local practitioners. It recommends a four-pronged future research agenda to address the theoretical and empirical puzzles that emerge from these exploratory findings.

To cite this paper: Ryan Saadeh,"Recovery in Post-Conflict Tripoli: Towards a Reconceptualization of Conflict, Peacebuilding, and Development in Tripoli, Lebanon", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2023-12-01 00:00:00. doi:

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/node/75939

INTRODUCTION

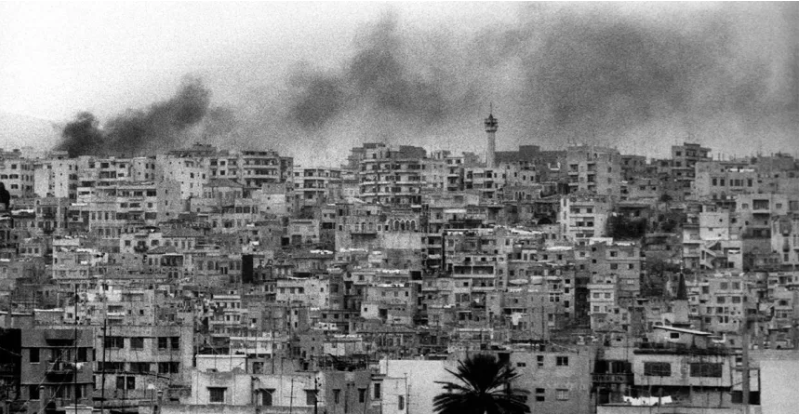

Since the end of the Lebanese Civil War, Tripoli has endured one of the highest densities and frequencies of violent conflict[1] and the highest levels of poverty in Lebanon and the broader region (UN Habitat 2016; UCDP 2021). Located 85 kilometers north of Beirut, Tripoli is Lebanon’s second largest city with a population of approximately 500,000 residents,[2] and it features disproportionately high rates of poverty amongst the metropolitan population compared to other regions in Lebanon (UN Habitat 2016). From 2008 until 2015, Tripoli witnessed numerous rounds of armed clashes in the neighborhoods of Jabal Mohsen and Bab al-Tabbaneh, which killed 200 people and injured more than 2,000. In 2017, the city also endured spillover battles with Islamist militant groups involved in the Syrian conflict (SFCG 2020). While there has since been a seemingly stable peace between the conflict-affected neighborhoods, the collapse of the Lebanese economy in 2019 and subsequent crises have brought unchecked structural violence and have tested the limits of the peacebuilding and development practitioners in the city.

Despite growing scholarly interest in the connection between poverty and recurring communal violence, the role of (under)development in conflicts that are framed along ascriptive identity groups, and vice versa, remains relatively under-researched, especially in ostensibly “sectarian” conflicts. Although conflict and development research has advanced significantly at the aggregate level, it has not as thoroughly uncovered sub-national patterns of conflict or variations in the types, forms, and consequences of violent conflict (Justino, Brück and Verwimp 2013, 4). A large segment of the literature on poverty and conflict can be summarized by the following statement: “pervasive poverty makes societies more vulnerable to violent conflict, while conflict itself creates more poverty” (Bannon 2010, 14). Yet even with empirical evidence of a correlation, the specific relationship between poverty and conflict remains unclear, as poverty and underdevelopment themselves are not guaranteed cause of violent conflict and depend drastically on context (Cramer 2003). Academic exploration of the relationship between underdevelopment and violent conflict has demonstrated that multi-dimensional approaches and contextual analysis are necessary to understand the particularities of this relationship in each setting (Cramer 2003, 2006; Stewart 2010; O’Gorman 2011; Langer, Stewart and Venugopal 2012).

There is limited scholarship on Tripoli in the fields of development and conflict studies, especially in comparison to the vast and comprehensive body of scholarship on such topics in post-war Beirut. This is partially due to Syrian-imposed restrictions on the Lebanese press during 1993-2005, i.e. the period when Syria exercised de facto control over the city (Gade 2015). To date, much of the knowledge production on contemporary conflict and development issues has come from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), whose reports have focused on violent conflict between the Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen neighborhoods, the rise of political Islamism within the city’s politics, or socio-spatial practices in the Tripoli urban area (Lefèvre 2014; Gade 2015; Micocci 2016; UN Habitat 2016; Knudsen and Gade 2017). A recent focus on analyzing the socioeconomics of sectarian conflict in Lebanon still largely articulates a return to class-based conflict as a stand-in for sectarian conflict, rather than an application of the ways sect and class are mutually constitutive, dynamic social entities. While studies that engage with the multi-level relationships between conflict and development dynamics in Tripoli exist, this scholarship is limited in quantity (Abou Mrad et al. 2014; Micocci 2016; Younes 2016; Al Ayoubi 2017; The Fares Center 2018).

This is particularly concerning when considered alongside the most visible analyses of the city, which generally frame the socio-economic and political setting in Tripoli’s conflict-affected areas on a spectrum from regional proxy violence to sectarian violence or assume that poverty and sectarian violence have a self-explaining relationship. However, existing scholarship tells us that not all conflicts become violent and not all impoverished cities suffer from communal violence (Cramer 2003; Willis and Rask 2018; Cammett 2019). Prevailing explanations assume that sectarianism drives the conflict in Tripoli, that inequality and underdevelopment drive sectarianism (and thereby conflict), and that conflict in turn drives underdevelopment. While such explanations can facilitate practical analysis of the conflict, I argue it is necessary to disentangle these assumptions as they can also impede the analysis of nuanced dynamics and mediating factors. Even so, these assumptions continue to shape the approaches of international donor organizations and international NGOs to peacebuilding and development interventions in Tripoli.

To deepen our understanding of the landscape and the challenges facing peacebuilding and development in contemporary Tripoli, this paper seeks to put insights from Tripolitan civil society practitioners in perspective with empirical and theoretical literature in the interdisciplinary fields of conflict and development studies. To do so, I identify and evaluate the challenges local practitioners are facing as they seek to address conflict in the urban region, as well as their understanding of conflict and development dynamics in the city. I also identify in which ways these circumstances may or may not be explained by existing theories of post-war development and identity group-related conflict. Thus, in contributing to the literature on contemporary Tripoli, this paper nuances current theories on post-conflict development using Tripolitan civil society as a case study. While this paper does highlight gaps in existing analyses of conflict processes in Tripoli, as well as their implications for program design and implementation, its primary focus is the ways in which local “doers” of peacebuilding and conflict response understand the factors shaping their environment.

To answer these questions, I take a meso-level approach to analyze both processes of conflict and efforts to prevent and respond to conflict within the post-war development context in Tripoli (Mac Ginty 2019). I first review the academic literature on post-conflict development, socio-economic inequality and conflict, and sectarian violence. I then situate a history of conflict and development in Tripoli within a broader history of uneven development in Lebanon in both the pre-and post-war periods. I then explore the perspectives of practitioners working in peacebuilding and development organizations in Tripoli, evaluating the common themes against existing reports and sources. Finally, I conclude with a future research agenda based on this analysis.

METHODOLOGY

This paper builds upon and connects scholarship in conflict and development studies to scholarship on Tripoli.[3] To this end, I employed a mixed-methods approach, drawing from existing reports, news articles, and analyses of conflict and development in Lebanon, as well as semi-structured interviews to conduct a case study of organizations working on peacebuilding and development in Tripoli. This paper refers to organizations working in these fields, as well as their employees, as “practitioners.”

In best practice for post-war reconstruction, development, and peacebuilding interventions, there is an academic and policy consensus that “local” participation increases the effectiveness of projects, reduces costs, and is more sustainable than external intervention (Mac Ginty and Hamieh 2010). While the frame of the “local” has been critiqued for its tendency to both overestimate and disregard local capabilities and for its treatment of the “local” as a monolithic entity, this paper follows the view that local approaches to development and post-conflict recovery are vital to the success of such efforts (Mac Ginty and Hamieh 2010; O’Gorman 2011). Local approaches “demand that external and national actors pay attention to the complexity of circumstances” within a given area, and these insights are valuable components of peacebuilding and development analysis (Mac Ginty and Hamieh 2010, 61).

Further, actors who constitute “the local” are diverse and, especially in post-conflict settings, cannot be reduced to a separation between civil society and state: Many individual actors “take on a mix of roles in their environment” (Pouligny 2005; O’Gorman 2011). The interlocutors I spoke with represent these fluctuating roles: All had worked for or in cooperation with international states and organizations or were funded by international donors; some had worked in a variety of capacities for the state, local NGOs, and/or INGOs. Interviewees remarked that local beneficiaries’ perceptions of practitioners were shaped more by practitioners’ class signals, attitudes towards locals, and the trust developed over time, rather than strictly by organizational or professional affiliation.

In addition to exploring local participation in peacebuilding efforts, this paper analyzes the meso-level processes of conflict and development in Tripoli, focusing on processes that take place at the community level or at the level of social groups and organizations (Balcells and Justino 2014). Conflict analysis is highly context-specific and requires inquiry around specific projects and programs, how their design responds to the conflict situation, and how their evaluation is inclusive of alternative forms of successful development (O’Gorman 2011, 57). The meso-level approach—particularly helpful for understanding approaches to conflict resolution, peacebuilding, and development at the program and project levels—rectifies this shortcoming (O’Gorman 2011, 56).

As Tripoli’s conflict and development dynamics diverge from other urban areas in Lebanon at the meso-level, there is debate as to whether Tripoli’s situation is “exceptional” (Gade 2015; SFCG 2020; Ibrahim et al. 2021). To understand the way development and local conflict dynamics both manifest uniquely and share characteristics with contexts elsewhere, it is necessary to investigate their coevolution and interplay.

To explore this, I conducted nine semi-structured interviews with representatives of Lebanese organizations working on the intersections of conflict and development. These interlocutors were selected using purposive and snowball sampling, based upon the following criteria: the entity is a (1) Lebanese civil society organization (CSO) or multi-organization initiative (2) with an office or operational staff based in Tripoli (3) whose mission focuses on either development or peace and conflict. The interviews were conducted virtually, recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. All interviews were anonymized. I then cross-referenced the emerging patterns and themes from the interviews with the desk research to draw conclusions about the relationship between conflict and development, the landscape facing local civil society[4] organizations working on both indirect and direct conflict programming, and recommendations for future research agendas.

BRIDGING CONFLICT AND DEVELOPMENT, CONCEPTUALIZING RECOVERY

This section situates contemporary Tripoli within the academic literature on development in post-conflict societies and the intersections of development and post-conflict reconstruction in divided societies. As a site of protracted urban conflict in a post-conflict state, Tripoli is a city at once post-conflict, pre-conflict, and in conflict (The Fares Center 2018). It is pre-conflict in that there is a potential absence of visible violence, despite the possibility or anticipation of its occurrence. It is post-conflict in that the contemporary context traces many of its roots to the Lebanese Civil War and the failures of the ensuing reconstruction period. It is in conflict in that there is an absence of a fully positive peace; moreover, the failures of development can constitute a form of structural violence against Tripoli’s residents. Scholars note that developmental factors can be triggers for violence, the end of violence, and post-conflict reconstruction, as well as vehicles through which structural and systemic violence may be perpetuated (Mac Ginty and Williams 2009, i).

While conflicts can become more or less violent, there are few truly “post-conflict” situations—wherein conflict ceases to exist altogether—and the characteristics of many “post-conflict” contexts deviate substantially from one another (Junne and Verkoren 2004; Brown, Langer and Stewart 2008). While “post-war” as a term can bring additional specificity (Suhrke and Berdal 2013, 6), for the purposes of this case study, I use “post-conflict” since the distinction between violent conflict and war in Lebanon’s context is blurry, and many instances of post-conflict violence may also be defined as small-scale wars in their own right. Although the beginning of Tripoli’s marginalization long preceded the Lebanese Civil War, many of the factors shaping the contemporary context can be traced to the failures of the post-war reconstruction era.

Poorly designed or managed post-war reconstruction often has far-reaching ramifications for the nature of the post-war society, some of which may be negative (Cramer 2006; Mac Ginty and Williams 2009). Because many conflicts have significant socio-economic roots, “attempts to return the economy to its pre-conflict state may perpetuate the economic grievances underlying conflict in the first place” (Brown, Langer and Stewart 2008). Negligent post-conflict development brings significant risks in divided societies, as empowering local interlocutors may reinforce divisions and may unintentionally favor majorities or minorities (Brown 2004, 113).

Lebanon illustrates the consequences of poorly implemented development. The neoliberal post-war reconstruction enmeshed rent-creation[5] and rent-seeking behavior with sectarian clientelism, fusing them in the core of the Lebanese political and economic systems. The entanglement of rents, sectarian politics, and elite patronage networks has led to a state of “de-development” in Lebanon, a term coined by Roy,[6] wherein the “economy is deprived of its capacity for production, rational structural transformation, and meaningful reform, making it incapable even of distorted development” (Roy 1999, 65; Sharp 2020, 7). In the case of Lebanon, post-war reconstruction did not lead to a new social contract or trickle-down development, but instead resulted in a confessional-rentier system that deepened the roots of the economic crisis and de-development in the country.

UNEVEN DEVELOPMENT OR “IDENTITY-BASED” CONFLICT?

Broadly speaking, conflict dynamics in Tripoli appear to reflect “an intensified and accumulated version” of contemporary national conflict dynamics in Lebanon and escalation of geo-political rivalries (Larkin and Midha 2015; Younes 2016). Yet, Tripoli distinguishes itself from Lebanon’s other regions both in density and frequency of violent conflict, as well as the marginalization it endures from state institutions, political leaders, and economic investment (Younes 2016). Over the past four decades, Tripoli’s regional economic standing has deteriorated, in part due to the rise in inter-communal “sectarian” violence and regional conflicts. Alongside this socio-economic decline, poverty and social tension have increased, leading to some fundamentalist radicalization and heightened focus on this issue in grey literature (Lefèvre 2014; Younes, 2016).

In most civil conflicts, the intensity of violence stems from “visible and felt inequalities at the local level” rather than the extremes of inequalities, meaning those between the richest and poorest segments of the population (Cramer 2003, 405). While most indicators of poverty evaluate vertical inequalities, or differences between individuals or households in a given society, there is strong evidence that the presence of horizontal inequalities (HIs)—inequalities between culturally defined groups—significantly raises the risk of conflict in a given setting (Stewart 2010). This theory is of relevance to Lebanon, which is broadly characterized by horizontal inequalities between regions, as well as inequalities—real and/or perceived—between sects (Makdisi 2004; Salti and Chaaban 2010; Traboulsi 2012; Sanchez 2018).

In the conclusion of a report on sectarianism and development in Lebanon, Christophersen (2018, 1) optimistically writes: “When all Lebanese start to receive protection, social services, and opportunities for education and public sector employment from the state, they will no longer be dependent subjects of a sect leader who is now satisfying many of these needs.” However, this assumes a good-faith positioning of the government vis-a-vis sectarian leaders. In practice, the governance system is built upon horizontal deals among oligarchs, underpinned by vertical patronage networks within each sectarian community (Diwan and Haidar, 2019). These politicians and sectarian leaders rely on one another to sustain the sectarian system which grants them legitimacy and ensures their continued power at the expense of effective national development (Dibeh 2005; Diwan and Haidar 2019). The three main dimensions of inequality in Lebanon may thus be summarized as (1) the clientelistic-rentier system, (2) the vertical inequality between the rich and poor, and (3) geographical inequality between Lebanon’s more developed urban centers and underdeveloped rural peripheries (Christophersen 2018).

Power-sharing agreements, as in the case of Lebanon, are often correlated with a reduced likelihood of conflict (Stewart 2008, 2010). Where HIs have been a major cause of conflict, scholars argue that post-conflict development must include policies that focus on reducing HIs (Langer, Stewart and Venugopal 2012). Yet for Lebanon, where the power-sharing system is disincentivized from “desectarianizing” social relations, the opposite occurred (Sanchez 2018). State policies in the post-war period worsened HIs between Tripoli and Lebanon’s other urban regions. Furthermore, sectarian power-sharing models may prevent equitable development because they require consensus on nearly every decision (Christophersen 2018).

Economic inequality cannot be separated from the social, political, cultural, and historical. Cramer (2003, 404) argues that it is the “historically established social relations that lie behind observable manifestations of inequality [that] are more important, for understanding the consequences of inequality, than those manifestations themselves.” The perception of unevenness or inequality is just as important as its existence, especially in societies with identity-based divisions where groups may interpret difference or relative deprivation through an identity-based lens (Mac Ginty and Williams 2009, 6; Stewart 2010).

In the context of Lebanon, I will conceptualize sects as “social entities” whose bounds and construction are continually being negotiated and whose salience may increase or decrease at any given time (Traboulsi 2014). Many sectarian conflicts that are putatively religious in nature or character are found to primarily implicate factors such as “political power, economic resources, symbolic recognition, or cultural reproduction” (Brubaker 2015, 1). “Sectarianism”—or, more descriptively, “sectarian conflict”—can be understood as the politicization of religious difference (Cammett 2019). Yet, as with poverty, the mere existence of communal identity—sectarian or other—does not automatically lead to violent conflict. Thus, the question arises of which factors lead to sectarian identity being politicized as a locus of conflict (Cammett 2019). While the conflict in Tripoli is frequently labelled as sectarian violence, it is uncertain to what extent politicized identity or perceptions of relative deprivation vis-a-vis other sects plays a role in the violence.

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: TRIPOLI’S LONG DOWNTURN

The context of the formation of the Lebanese state and the Lebanese Civil War thereafter is crucial to understanding Tripoli’s contemporary development and conflict dynamics. These dynamics can be traced from Ottoman rule in the nineteenth century through the rapid economic and political marginalization of Tripoli in the wake of World War I with the creation of mandatory Lebanon. Following the war, the coalescence of rentierism with sectarian clientelism in the Lebanese political system exacerbated the developmental neglect that allowed the conflict between Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen to protract long after the war officially ended.

Throughout the Ottoman Empire, Tripoli was a provincial capital and a major port of Syria (Reilly 2016). Yet, towards the end of the Ottoman era, two trends emerged that would have lasting impacts on the development of Tripoli and Lebanon. First, beginning in the seventeenth century, the rise of competing ports along the Eastern Mediterranean challenged Tripoli’s role as a central port (Abou Mrad et al. 2014). This marked the beginning of a long period of decline in strategic, economic, and political standing, which would continue more or less uninterrupted until the present day (Reilly 2016, 2017; Knudsen and Gade 2017). Second, outside of Tripoli, conflict in the Mount Lebanon region would lay the roots of Lebanese sectarianism. These conflicts led to uneven access to socio-economic privileges that primarily benefited Maronite Christians and then the Druze (Makdisi 2000; Traboulsi 2014, 19). Among other impacts, this was reflected in different levels of growth between the urban center and the peripheral regions, including unequal access to “development, resources, state services, knowledge and health” (Traboulsi 2014, 19)

With the breakup of the Ottoman Empire following World War I, these trends continued and were aggravated by the birthing pains of the new Lebanese state. French divide-and-rule policies during the mandate period incited the beginnings of widespread politicized ethno-religious identity in Lebanon (Makdisi 2000; Traboulsi 2014). Incorporated into the new Lebanese state, Tripoli both was isolated from Syrian trade and marginalized from the regional center of Beirut (Abou Mrad et al. 2014; UN Habitat 2016). Initially, Tripoli’s residents met separation from Syria and inclusion in Lebanon with resistance (Younes 2016; Knudsen and Gade 2017). This has led some observers to argue that Tripoli has been deliberately excluded from the Lebanese state or punished for the initial resistance to the formation of the Lebanese Republic (Ibrahim et al. 2021). Others, however, argue that this analysis exceptionalizes Tripoli, as multiple sects and areas similarly protested the Lebanese state’s creation, and that Tripolitans readily participated in the newly formed government (Traboulsi 2012, 75; Ibrahim et al. 2021).

Following Lebanon’s independence, the National Pact of 1943 further solidified a parliamentary power-sharing system with representation allocated on the basis of sectarian affiliation. Cumulatively, these foundational documents codified sectarian identity into the very framework of the Lebanese political system, requiring political representation to be constantly mediated by confession. By the mid-century, fueled in part by population growth from rural immigration, Tripoli was experiencing significant socio-economic marginalization from the urban center and capital and was cited as the country’s poorest city, even as Lebanon benefitted from a relatively stable and growing economy (Makdisi 2004; Knudsen 2017). In 1955, the flood of the Abu Ali river, which “separates the north-eastern section of the city, traditionally inhabited by the lower-income population of Bab al-Tabbaneh and Jabal Mohsen, from the historic city center towards the south,” led to deepening socio-spatial segregation (Micocci 2016). In the aftermath of the flood, reinforced concrete walls were built alongside the river, leading to the demolition of approximately 2,000 residential units and displacing many (Nahas and Yahya 2001). This led to vast environmental damage, deepening impoverishment, and the disruption of urban life alongside the river (Micocci 2016). Upper-class families left the “old city” and developed neighborhoods south of the river, while migrants from rural areas settled in the city center (Nahas and Yahya 2001; Abou Mrad et al. 2014; UN Habitat 2016).

In 1968, the Rashid Karami International Fair was established near the central business district and less than a kilometer away from the seaside, “aimed at promoting Tripoli as the city of modernization and recreating Tripoli’s role in the region” (Abou Mrad et al. 2014). Although nearing completion when the civil war broke out, it has not been worked on significantly since the 1970s (UN Habitat 2016). Throughout the 1970s Tripoli lost its former role as the main maritime port of central Syria to Tartus, all while losing port market share within Lebanon to Beirut (UN Habitat 2016).

While Lebanon's macroeconomic outlook during the 1960s and early 1970s appeared to grow, sub-national development was becoming increasingly uneven by region, class, and sect (Makdisi 2004; Traboulsi 2012). These growing sect-based socioeconomic disparities strained the country’s confessional political system. From 1975-1990, the country endured a series of internationalized battles and wars that would come to be known as the Lebanese Civil War. In Tripoli, this manifested in several leftist and rejectionist political movements, which would come to be involved in the armed conflicts from 1975 onward (Younes 2016; Knudsen 2017). Uneven socio-economic development was only one factor contributing to the war’s onset. Yet, once conflict was in motion, the spoils of the war economy became a primary driver of the conflict, alongside the fuel of sectarian violence and the “multiple and persistent” external military and financial interventions (Makdisi 2004, 6).

In November 1976, the Syrian army entered Tripoli and began to exert control over the city and the surrounding region, creating “alliances, conflicts and divisions still present in Tripoli today” (Gade 2015, 20). Prior to the 1970s, Alawis and Sunnis in Tripoli and in Bab al-Tabbaneh belonged to roughly the same social strata and political realm. However, amid increasing polarization between parties and movements closer to the PLO and aligned with Syria, the politicization of identity began, with Tripoli’s political field split “between winners and losers of the Syrian presence” (Gade 2015, 20).

The Islamic Unification Movement, a Sunni anti-Syrian party and militia, briefly held a foothold in the city, and even after its defeat in 1985, former members continued to fight the Syrian occupation in Lebanon (Younes 2016). This in part led to the 1986 Bab al-Tabbaneh massacre, enacted in retaliation by Syrian powers in alliance with the mainly Alawite Arab Democratic Party (ADP), which continues to play a key role in collective memory (Milligan 2012; Kortam 2017; The Fares Center 2018; UN Habitat and UNICEF Lebanon 2018). These initial clashes which took place in the 1980s between Jabal Mohsen and Bab al-Tabbaneh would evolve into an intractable conflict. By the end of the civil war, many old city inhabitants moved to the suburbs during a construction boom. As the city expanded outwards, the socio-economic conditions in the city center continued to deteriorate. With outmigration of Maronite Christians during the war, the city lost its multi-confessional makeup, with a post-war composition of nearly 90% Sunni Muslims and a substantial minority of Alawites in the Jabal Mohsen neighborhood (UN Habitat 2016).

Nationwide, fighting brought an estimated $25 billion in physical damages, more than halved Lebanon’s GDP, killed over 150,000 people, and displaced approximately 800,000 (Knudsen and Yassin 2013). Most of the fighting and resulting infrastructural damages took place in the Beirut theater of the war. Yet Tripoli, too, had suffered, with progressive deindustrialization and closure of infrastructure services such as the railway, fairgrounds, and refinery (UN Habitat 2016). Already marginalized pre-war, Tripoli “fared worse relative to the national average in the country’s post-1975 downward economic spiral” (UN Habitat 2016, 45).

CONFLICTUAL DEVELOPMENT IN LEBANON’S RECONSTRUCTION ERA

The war in Lebanon formally ended with the signing of the Ta’if Agreement in 1989. Ta’if allowed continued Syrian dominance over Lebanon’s security and foreign-policy posts while allowing then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri to lead the economy and reconstruction process (Sharp 2020). To implement such plans, Lebanese leaders had to be mindful of and maneuver around Syrian economic interests and stakes in Lebanon (Osoegawa 2013, 74, 132). This has led some observers to suggest that Syrian powers deliberately hampered economic and infrastructural development in the reconstruction period (Milligan 2012; Ibrahim et al., 2021). However, this does not explain the lack of local investment from wealthy Tripolitans—that is, it does not account for why “capitalists are not courageous enough” to invest in the city (Ibrahim et al. 2021).

The failures of the Lebanese reconstruction period demonstrate that “rebuilding can play a central part in maintaining conflict” (Sharp 2018). The concentration of reconstruction investment and efforts in Beirut furthered instability and conflict in Lebanon, and post-war reconstruction catered primarily to elite society while undeserving and further marginalizing peripheral regions (Traboulsi 2014). A sole private company, Solidere—founded by then-PM Hariri—was given authority to reconstruct the city center. There is much scholarship investigating the political economy of the Solidere-led reconstruction, which finds Solidere was “at the heart of the spiraling levels of national debt, and contributing significantly to the state’s fiscal crisis, corruption and social inequality” (Sharp 2020). Solidere was only accountable to the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), an entity founded in the early years of the war with unprecedented power to direct the country’s reconstruction (Baumann 2017). Despite the National Physical Master Plan for the Lebanese Territory (2005) requiring the CDR to plan for nationally balanced development, recent studies have shown that procurement for CDR funds is uncompetitive and that the government’s distribution of development assistance funds to municipalities is balanced across sects but not justified on the basis of need (Salti and Chaaban 2010; UN Habitat 2016; Atallah et al. 2020). This is particularly troubling as public infrastructure spending has been shown to worsen inequalities between districts, rather than promote equitable development (Sanchez 2018). As Lebanon has one of the worst public infrastructure systems in the world even prior to the current crises, reliable access to resources, including electricity and water supply, declines outside the capital (Sanchez 2018).

The rentierization of the Lebanese economy in the post-war period was and continues to be a driving factor of uneven and underdevelopment in Lebanon. Economic rents as a share of GDP rose from 9% to 23% between 1990 and 1998 to be one of the highest in the world (Traboulsi 2014). The confluence of the profitable reconstruction period with Gulf rentierism contributed to the emergence of a rentier-capitalist upper class that possesses most of the country's wealth (Baumann 2016, 2019). In 2019, the top 10% of the adult population received 55% of the national income of Lebanon on average; recent estimates put that share above 70% (Assouad 2019; Cornish 2020). The failed post-war development approach worsened inequality and sowed the seeds for the present financial collapse via profit-driven debt mismanagement, leading to “the survival of the war economy” and an overall situation of de-development (Dibeh 2005; Srouji 2005; Gaspard 2017; Christophersen 2018; Chaaban 2019).

Lebanon’s wealth gap is particularly stark in Tripoli, where despite being the most impoverished city, there is also a high proportion of millionaires and billionaires (Ibrahim et al. 2021). Tripoli is home to numerous super-wealthy families, including the Mikati and Safadi families, who have established philanthropic foundations to support development projects in the city (Traboulsi 2014; Cornish 2020). Political patrons control security, service provision, and access to public goods encompassing water, electricity, and employment, and have powerful leverage for influence of deprived urban youth (Knudsen 2017). In the inner city of Tripoli, with its high degree of state retrenchment and violent conflict, private foundations have stepped up to dispense aid through patronage networks in place of public social services.

PROTRACTED CONFLICT IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENT

In 2005, following popular pressure in response to the assassination of PM Hariri, the Syrian army withdrew from Lebanon, dividing Lebanese political society into pro- and anti-Syrian camps. Hariri’s assassination led to a political shakeup in the Sunni leadership in Lebanon, which profoundly impacted Tripoli as politicians could not establish a unified approach to Tripoli’s political and socio-economic challenges (Younes 2016, 11). The vacuum in religious and political leadership led to alternative political-sectarian institutions competing to represent various parts of the Tripolitan Sunni community (Younes 2016). In a system which predicates public service and infrastructure on patronage politics, this has proven detrimental for residents with rising neglect of the population’s basic needs (Younes 2016; Knudsen 2017).

The fomenting divisions did not turn violent until May of 2008, when clashes in Beirut triggered fighting between primarily-Sunni Bab al-Tabbaneh, Qobbeh, and Beddawi on the one hand and primarily-Alawite Jabal Mohsen on the other (Al Ayoubi 2017, 13). In 2013, twin car bombs—the two deadliest since the civil war—struck Tripoli’s al-Taqwa and al-Salam mosques during Friday prayers, sparking rounds of retaliatory violence (Larkin and Midha 2015, 182). The Syrian uprising in 2011 exacerbated these clashes, which intensified with the arms proliferation that regional players in the Syrian conflict sponsored (Al Ayoubi 2017, 13–14).

These clashes were eventually contained in March 2014, with a government security plan deploying Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) troops to Tripoli; however, this plan did not address systemic issues underlying the conflict or the city’s developmental needs and therefore did not bring a holistic peace (Al Ayoubi 2017; Knudsen 2017). Further, some are suspicious that it was the security plan that was truly responsible for quelling the violence, speculating about backdoor deals or other forces at play and questioning the role of the LAF (The Fares Center 2018). Still, street violence and the threat of future armed clashes continue to impact residents’ daily lives, and the area’s securitization intensifies a combative environment (Larkin and Midha 2015).

Since 2019, Lebanon has experienced an ongoing financial crisis which has been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic and the August 2020 Beirut Port explosion. The Lebanese pound has lost around 90% of its previous value in the past two years, marking one of the most severe economic crises globally since the mid-nineteenth century (El Dahan and Bassam 2021; World Bank 2021). The World Bank estimates that in 2020, real GDP contracted by 20.3%, with GDP per capita falling by about 40% in dollar terms—a contraction so brutal it is usually associated with conflicts or wars (World Bank 2021). Because the Lebanese state failed to develop stable infrastructure, residents rely on private water trucks and generators, yet with the spiraling financial crisis, these commodities’ supply chains are interrupted, and much of the country is plagued by shortages of fuel, electricity, medicine, food, and other necessities (Christophersen 2018; Eltahir 2021; Eltahir and Abdallah 2021).

In March 2021, the UN estimated that nearly 80% of the Lebanese population lived in poverty, with extreme poverty reaching an estimated 36% (UN OCHA 2021). For Tripolitans, among whom pre-2019 poverty levels were estimated to be above 60%, the economic situation has deteriorated drastically. As one interviewee described it: “the economic crisis has had its lion's share in Tripoli.”

Somewhat surprisingly, a 2020 Search for Common Ground conflict analysis study found that sectarian divisions, despite their prominence in media, went unmentioned by focus groups and key informant interviews (SFCG 2020). While this might suggest increased social cohesion and unity, a less optimistic outlook might suggest that economic and social issues have temporarily overtaken political issues and that social tensions nevertheless arise from economic hardship (SFCG 2020, 44, 32). I now turn to a meso-level analysis of civil society stakeholders to unpack the ambiguities and challenges of conflict-sensitive programming in Tripoli.

SITUATING TRIPOLI WITHIN THE CIVIL SOCIETY LANDSCAPE IN LEBANON

Myriad Tripolitan civil society organizations are working to promote development and peacebuilding at a local level, and Lebanon has one of the liveliest civil society landscapes in the Arab world. Non-state providers of welfare—whether NGOs, private foundations, or sectarian associations—often feature more prominently in the everyday lives of the poor than the state (Cammett 2015, S76).

Lebanese CSOs focus more on services and local development than policy issues (Seyfert 2014; Transtec and Beyond R&D 2015). Since the early 2000s, the quality of government-provided social services has deteriorated, prompting CSOs to focus on providing basic services to citizens, expanding to refugee communities following the Syrian crisis in 2011 (Transtec and Beyond R&D 2015). Surveys found that over 78% of CSOs do not closely follow their mission statements, with most NGO survey respondents multi-selecting a majority of all possible answers in a list identifying their activities (Seyfert 2014; Transtec and Beyond R&D 2015). The majority of CSOs work at the national level, with under 40% consisting of local or community-based organizations (Transtec and Beyond R&D 2015).

International development aid, especially post-1990s, has increasingly focused on issues of peacebuilding, conflict resolution and prevention, and security (O’Gorman 2011). The rise of a dominant policy discourse which advocates for a joint peacebuilding-development agenda has contributed to an aid landscape replete with NGO-led peace and development projects and funding for “quick-impact economic and public works projects to promote peace dividends,” with significant scholarly and practitioner debate regarding their impacts and efficacy (O’Gorman 2011, 66). While international organizations and INGOs regard local civil society as “a key transmission agent” for conflict and development work, their intervention—coupled with their relative power in terms of funding—can result in a post-conflict civil society that is developed in the image of Western models and lacks effective roots in the local society (Mac Ginty and Williams 2009, 82–83). Partnerships with local civil society organizations thus reflect the tensions and tradeoffs between donor agencies, local CSOs’ ability to independently critique said agencies, beneficiaries’ needs—real and/or perceived—and CSOs’ organizational strategy and capacity (O’Gorman 2011). While there is significant literature on the impacts of development aid on organizations, fewer analyses exist of the implementation and evaluation of program- and project-level functions by local practitioners themselves.

Although many Tripolitan CSO were established before the 2008 conflict, the organizations I interviewed were largely founded in the context thereafter. The longest-operating CSO was UTOPIA Organization Lebanon. It was conceptualized in 2010 as an investment-oriented initiative and expanded its mission in 2011-2012 in response to the Syrian conflict and violence in Tripoli. At present, UTOPIA focuses on achieving social justice, with activities ranging from advocacy to community service, youth and women’s empowerment, educational tourism, and more (UTOPIA 2018). In response to the 2013 mosque bombings, civil society leaders launched the Coalition of Campaigns Against Violence in Tripoli (CCAVT). This coalition of existing initiatives united to formulate a crisis cell, coordinate infrastructure repair, and establish support groups (CCAVT 2013). The Coalition ended its operations by 2015, largely due to reduced funding. Some of these projects were funded by the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Office of Transitional Initiatives (OTI). Lebanese nationals who worked within the OTI frequently went on to form other coalitions and projects. Following the end of OTI funding, several peacebuilding and development experts organized on a volunteer basis to develop the grassroots Roadmap to Reconciliation in Tripoli (RRT) initiative in 2015, with support from the Forum for Cities in Transition Tripoli team (Al Ayoubi 2017). The project involved support from many pre-established organizations, including Peace Labs, which couples interdisciplinary research methods and evaluation with field practice to support communal-conflict transformation (Peace Labs - About Us).

Informed by the RRT, Tripoli residents and activists founded a community center in a rehabilitated building on a former frontline between Jabal Mohsen and Qobbeh, a strategic shared space that transverses conflict lines (SHifT SiH - About). The SHiFT Social Innovation Hub now incubates numerous independent initiatives and operates programs relating to business and social development and empowerment, vocational and educational training support services, and reconciliation and peacebuilding initiatives (SHiFT SiH - Programs). The breadth and depth of SHiFT’s programming is reflected in the interview sample, which included more interviews from this organization relative to the others.

The following insights are limited in several ways. First, the sample size is small, with several interlocutors belonging to one organization. Second, these organizations—which overlap in characteristics and scope—may overrepresent a particular segment of the peacebuilding and development field in Tripoli, due to the snowball sampling method and the inability to fulfill scheduled interviews with practitioners of other organizations due to electricity and internet outages. Third, this research did not interview these CSO’s beneficiaries, nor did it attempt to evaluate effectiveness in programming methods. Fourth, while all organizations self-identified as non-sectarian, independent, and participatory programs, I was unable to independently verify that local beneficiaries perceived these organizations in the same light.

Despite these limitations, by focusing on practitioners’ understandings of their work and their environment, this research is valuable insomuch as these perspectives shape the work that is being done and can be assessed against other sources and scales to substantiate the emerging themes.

1. Untangling Tripoli’s Conflict Economy

Many recent process-driven analyses of conflict in Tripoli often rely on frameworks of extremism, radical Islamism, or Syrian-Lebanese relations to explain conflict occurrence (Lefèvre 2014; Knudsen 2017). However, it is clear from other research (Carpi 2015; Larkin and Midha 2015; Younes 2016; Knudsen 2017) and interviews that there are more levels of analysis that are still not understood, and that the aforementioned frameworks alone are insufficient to explain violence and conflict participation at the micro-level. My research confirms that the relationship between poverty, inequality, and conflict is not straightforward. During conflict, shortages and heightened risk can generate some high-return opportunities (Cramer 2006). Nearly all interviewees expressed the opinion that while there was a relationship between poverty and conflict, poverty was not the main driver of the conflict. One interviewee noted that many of the participants in violent conflict are comparatively well-off, in that they are not suffering from poverty or classified as vulnerable.

Even to the interlocutors working on peace and conflict in Tripoli, the dynamics and mechanisms of violent conflict mobilization are nebulous. One interlocutor called these dynamics “magical,” referring to their mysterious processes and indiscernibility (Interview 8/19/2021a). Another pointed to the conflict as one that had become so intractable that its dynamics were that of a “living organism” or “creature” that, when “poked” by an event or intervention, “would react by generating more conflicts.”

However, poverty and/or lack of empowerment clearly can play a role in participation. One interviewee explained that the “fighters” make marginal profits from the difference in overhead given by “frontline leaders” or “politicians” and the real costs of weapons. Another cited the out-of-reach cost of the weapons that were used in the clashes despite the areas’ impoverishment as evidence of war-sponsors, under the auspices of well-established political parties: “nothing is going to happen in those [conflict-afflicted] regions without them knowing where the money is coming from and who is channeling those weapons.” Other reports similarly cite that “receiving money to fight in battles was often not only described as a one-time incentive but rather as a sustainable way to improve the precarious economic situation” for young men in the conflict-affected areas (Younes 2016, 16). Many interviewees expressed that the high rate of poverty provides a base of exploitation from which political and sectarian leaders were able to draw supporters to stoke violent conflict.

The war economy certainly plays a role in the most impoverished sections of the city. One interlocutor reported that residents of the conflict-affected communities sometimes expressed that “if the fighting returned, some money would come back to this city. Now, there is no conflict. Okay, bravo, but now we don’t have money, we’re suffering, we are dying.”

Another interviewee shared that a woman participating in their NGO’s activities disclosed that when her husband, who was a frontline leader, was in control, the family had more money from investment in the conflict and that both sides were receiving significant funds. After her husband was forced to flee with the implementation of the security plan, she found herself in a less empowered position.

Additionally, multiple reports have noted that the conflict in Tripoli is more often articulated in terms of politics of intervention rather than social relations or sectarian conflict, a perspective corroborated by my interlocutors (Transtec and Beyond R&D 2015; Younes 2016). Nearly all interlocutors noted that without political intervention, or “a political decision,” neither the city’s poverty nor the fighting would be as prevalent. Many interviewees used the language of a top-down political “decision” to either start or stop fighting, though who was making the decision (whether state or non-state leaders, for example) was generally left unspecified. Larkin and Midha identify a key outline of Tripoli’s ongoing war economy, which “functions through a three-tier hierarchy of ‘funders’, ‘mediators’ (field commanders) and ‘fighters’. In Bab al Tabbaneh the militia funders are mainly local politicians—Mikati, Safadi, Hariri, Kabbara, Karami—in coordination with Gulf States...while the field commanders are often merchants...or religious clerics” (Larkin and Midha 2015, 194). Those who are tasked with fighting are drawn from marginalized segments of the population (Younes 2016; Kortam 2017). Here, the involvement of external actors is corroborated: “Street clashes and subsequent truces are often orchestrated and managed by political elites to pressure government policies or consolidate neighborhood support” (Larkin and Midha 2015, 202).

Lastly, several interlocutors expressed that conflict in Tripoli was not only a microcosm but a proxy for conflict at the national level with regard to contentious governance and policy-making: “Whenever there is a problem, in any country, for sure there will be a reflection in Tripoli because it is a community where conflicts are used to send messages between countries.” Here, external actors—whether regional or national—transpose their conflicts on Tripoli’s local theatre, as “local” conflicts are “cheaper and more manageable” than a war in the Lebanese capital (Larkin and Midha 2015, 198–199). Indeed, data on the conflict in Tripoli shows a cyclic character wherein local conflicts are preceded or sparked by external events (Knudsen 2017, 76). Similarly, several interviewees commented on the changing “faces” of the conflict, hinting that the Western perspective of the conflict as sectarian or solely a proxy war is superficial and masks underlying dynamics. Extreme deprivation is the conflict’s current “face.”

2. The Role of Structural Violence in Underdevelopment

Looking beyond direct violence, interviewees have adapted numerous approaches to respond to the symptoms of slow or structural violence. When asked about the most salient factors contributing to conflict and violence, interviewees highlighted additional variables that have been explored in different fields: low levels of education and lack of related resources; psychological issues, including depression, substance abuse, and intergenerational traumas; high rates of unemployment; and the more survival-oriented challenges stemming from the recent shortages and the devaluation of the Lebanese pound. There was no discussion of perceptions of horizontal inequalities as contributing to violence. Although largely anecdotal, one interlocutor stated that poverty was deep and widespread enough for Sunni and Alawite communities to recognize their mutual suffering: “They are both in the same crisis now. Sunnis from Qobbeh or Tabbaneh do not perceive Alawites from Jabal Mohsen as ‘ya lateef, you are doing better or slightly better (than us)’. No, the situation is the same.”

Here, the further entanglement of conflict, development, and poverty makes establishing a causal relationship difficult. As a result, each of the organizations I sampled was working across the realms of social and business development, humanitarian response, conflict prevention and community peacebuilding, vocational training, and more. Most stressed the need for participatory and holistic interdisciplinary approaches and understood both poverty and conflict as multi-level issues. Whether these provisional approaches can sufficiently counteract the structural issues that underlie these visible manifestations of the lack of public services and development is uncertain, a harsh reality of which many interlocutors were acutely aware and critical. In fact, one interviewee described the older generation of seasoned practitioners in Tripoli as “drained, dissatisfied, frustrated... and utterly depressed” due to the insurmountable challenges facing development in the city.

3. Role of CSOs Between Funders, Beneficiaries, and Government

Over the past few decades, there has been a shift from donors providing “program” or “core” funding, which covers basic overheads for an NGO’s operations, to providing “project” funding, which targets specific projects and limits how the funds may be used (Seyfert 2014). This gives donors greater control over project outcomes. These donor requirements structure NGOs’ project implementation by influencing beneficiary targeting, regulating project timeframes, and impacting the ways and means NGOs evaluate and conceptualize their projects (Seyfert 2014). This does not mean that NGOs are passive recipients of donor interest, as they are often able to shape the ways in which donors target program funding (Seyfert 2014).

Most interlocutors noted challenges of coordination between NGOs in Tripoli, citing issues in inter-organizational trust, duplication of interventions, and uneven programming relative to various areas of need. Notably, nearly all organizations I interviewed had collaborated with one another in the past, whether through coalitions or individual team members' involvement across multiple projects over time.

Since the civil war, there have been several attempts to create coordination mechanisms between NGOs, but these have had relatively minor impacts on the political sphere (AbiYaghi, Yammine and Jagarnathsingh 2019). When coordination is successful, its mechanisms “often appear to be project-based and thus time- and resource-bound” (AbiYaghi, Yammine and Jagarnathsingh 2019). Rather than seeing the proliferation of NGOs in Lebanon as evidence of a vibrant civil sector, it can be understood as a fractionalization that confines local CSOs to an implementation role with limited development and policy impact on a larger scale (AbiYaghi, Yammine and Jagarnathsingh 2019). However, of the CSOs I interviewed, there is demonstrated momentum between organizations and their broader coalitional networks.

Many CSOs consider their relationship with Lebanese institutions to be ineffectual (Transtec and Beyond R&D 2015). Each of the represented organizations had some degree of collaboration with the local municipality, yet none expressed having a relationship with the national government. Those that discussed coordinating with the municipality, expressed doing so both out of practicality and in the spirit of trust-building between beneficiaries and the government. Despite this element of collaboration, many acknowledge the municipality was unproductive, inefficient, and, in some instances, corrupt.

Similarly, many interlocutors paraphrased beneficiaries’ perceptions of some NGO workshops and lectures as superficial, which may center the donor-driven and professional interests of NGOs. Interviewees noted the challenge of overcoming these perceptions, presenting their long-term engagement with and employment of beneficiaries as a strategy for improving participation and outcomes. All cited the importance of participatory, flexible, and community-driven approaches with a high degree of trust and commitment between beneficiaries and NGO staff.

The issue of “local” participation and trust was nuanced throughout these discussions as every interviewee was Lebanese, most were from the Tripoli urban area, and only a couple were from the “marginalized” areas of the city. Here, insider-outsider perceptions in practitioners were articulated through varying frameworks: for example, the apparel of a given staff member, the degree of saviorism or pitying attitude towards beneficiaries, and the perceived “localness” of the NGO all were said to impact how a given individual was understood by beneficiaries. Further, practitioner organizations that specialize in conflict mitigation and prevention and that work with former fighters, such as Fighters for Peace and the Permanent Peace Movement, were cited as better positioned to engage with fighters in marginalized areas despite being “outsiders” in terms of sectarian affiliation or region of origin.

4. Post-2019 Prospects for Practitioners

When asked about the new opportunities that have arisen in the wake of the 2019 uprisings, interviewees’ perspectives differed significantly. Some cited the continuing efforts of committed NGOs as a positive. Others pointed to an awakening in the popular political consciousness and attention to structural and systemic issues of the Lebanese political system and Tripoli’s display of a unified front even among divided communities. One described improved perceptions about the city in popular opinion, and another increased INGO and international attention to the city’s situation.

When asked about the challenges, participants listed the depth of poverty and the spiraling financial crisis with its related shortages. The lack of electricity and fuel threatens continued organizational operations and service delivery to beneficiaries who, in turn, are more focused on meeting basic survival needs than participation in programs. Additionally, one interviewee referenced the long-term “brain drain” and emigration of people who might otherwise be in a position to support and uplift their communities. Lastly, one cited concern that the new “face” of the conflict would be one of violence related to survival and that widespread deprivation, as has already been seen in clashes over shortages of fuel, might escalate into broader violence: “The conflict is changing from a political and religious dynamic to an economic and basic survival dynamic. It is a conflict about resources.”

It remains to be seen how the intensifying effects of structural violence and the repercussions of de-development will interplay with conflict dynamics in the city. Scholars and practitioners alike should be mindful of and strategize for possible long-term outcomes of these conditions which continue to worsen.

CONCLUSION

This paper has sought to advance an understanding of the relationship between the conflict and development contexts in Tripoli. It found that while horizontal inequalities and sectarian identity do play a role in conflict, this is not due to relative deprivation, nor the politicization of sectarian identity, nor poverty alone. Rather, it argued that the horizontal and vertical relations which constitute the political sectarian governance system in Lebanon are implicated in the marginalization, underdevelopment, and structurally violent situation in the city. The present state of de-development thus poses a near-insurmountable challenge to development practitioners, who, despite adopting innovative mechanisms and strategies in their organizations’ operations, are in many ways struggling to address the violent symptoms of these structures. Despite this, these practitioners’ efforts are not futile and indeed make a positive impact and play a crucial role within their communities.

Based on my analysis, I suggest a four-pronged research agenda. First, the case study of Lebanon’s post-war development exemplifies the need for more research on failed post-conflict recoveries. While there is literature discussing best practices and challenges (Junne and Verkoren 2004; Barakat 2010), there are few resources that have investigated protracted situations of de-development or conflict-sensitive development programming in circumstances where bad development practice is the norm. In light of voluminous literature regarding the failings of Lebanon’s neo-liberal reconstruction (Adwan 2005; Dibeh 2005; Höckel 2007; Mac Ginty 2007; Leenders 2012; Baumann 2017; Sharp 2020) there has yet to be a broader engagement with development practitioners—especially at the international level—as to how this has realistically shaped the developmental field. These topics have somewhat been addressed in the literature on “fragile” or “failing” states, but this literature suffers from similar normative issues of Western liberal “peacebuilding” and related concepts of state- and nation-building and is therefore ill-suited to the Lebanese context (Bøås and Jennings 2005; Kosmatopoulos 2011; O’Gorman 2011; Fregonese 2012; Melber 2012; Hazbun 2016).

Second, there should be more investigation of incentive mechanisms to promote nation-wide development and disconnect it from the clientelistic structures that reinforce its failure. While many practitioners—especially local ones—are aware of the underlying barriers to development, there remains a segment of the developmental community that does not address the deep political roots of the current state of de-development. That is, for a holistic improvement of quality of life, it is necessary to address the entanglements of rentierism and clientelism within the governance system that disincentivize development for the elites who operate and benefit from the system's perpetuity. Here, the interconnection between activists and scholars of social movements would benefit them through sustained engagement with local practitioners and the development of sustained advocacy networks.

Third, there is a lack of micro-level studies of the political economy of violence in Tripoli, which can help frame targeted programming approaches and better position local practitioners to meet the needs of the population. Fourth, and most directly related to the limitations of this research project, the early insights expressed here may be evaluated and critiqued against further empirical research on the effectiveness of local interventions from a scholarly angle and beneficiary-centered perspective. While this paper has largely focused on challenges facing practitioners, this future research agenda may better identify and recognize these organizations’ successes, innovations, and recommendations.

In reconceptualizing the interplay between conflict and development dynamics in Tripoli, this paper has highlighted the challenges that de-development and structural violence pose to local civil society practitioners navigating their work. It remains to be seen how Tripolitan CSOs will approach the long-term implications of the current economic collapse, and while the conditions necessitate a humanitarian response, it will be crucial to address and strategize for the multilevel processes that contribute to violence in multiple forms.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AbiYaghi, Marie-Noëlle, Léa Yammine, and Amreesha Jagarnathsingh. “Civil Society in Lebanon: The Implementation Trap.” Text. Civil Society Knowledge Centre. Lebanon Support, January 8, 2019. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/civil-society-lebanon-implementation-trap.

Abou Mrad, Elias, Joyce Abou Moussa, Fabiano Micocci, Nadine Mouawad, and Marie-lyne Samaha. “Bab Al Tabbaneh-Jebel Mohsen: Inclusive Urban Strategy & Action Plan.” Diagnosis & Urban Scenarios Report Vol. 1, 2014.

Adwan, C. “Corruption in Reconstruction: The Cost of ‘National Consensus’ in Post-War Lebanon.” Lebanese Transparency Association, January 2005. https://www.eldis.org/document/A30239.

Al Ayoubi, Bilal. “The Roadmap to Reconciliation in Tripoli: Creating an Inclusive Process for Launching a Communal Reconciliation in Tripoli.” Roadmap to Reconciliation in Tripoli Project, April 2017.

Assouad, Lydia. “Rethinking the Lebanese Economic Miracle: The Extreme Concentration of Income and Wealth in Lebanon.” PSE Working Papers. PSE Working Papers. HAL, June 2019. https://ideas.repec.org/p/hal/psewpa/halshs-02160275.html.

Atallah, Sami, Ishac Diwan, Jamal Ibrahim Haidar, and Wassim Maktabi. “Public Resource Allocation in Lebanon: How Uncompetitive Is CDR’s Procurement Process?,” July 2020. http://lcps-lebanon.org/publication.php?id=359.

Azhari, Timour. “Why Thousands Continue to Protest in Lebanon’s Tripoli.” Al Jazeera English, November 3, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/3/why-thousands-continue-to-protest-in-lebanons-tripoli.

Balcells, Laia, and Patricia Justino. “Bridging Micro and Macro Approaches on Civil Wars and Political Violence: Issues, Challenges, and the Way Forward.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58, no. 8 (December 1, 2014): 1343–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002714547905.

Bannon, Ian. “The Role of the World Bank in Conflict and Development: An Evolving Agenda (English).” Text/HTML. World Bank, 2010. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail.

Barakat, Sultan. After the Conflict: Reconstruction and Development in the Aftermath of War. Illustrated edition. London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2010.

Baumann, Hannes. Citizen Hariri: Lebanon’s Neo-Liberal Reconstruction. 1st edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA, 2017.

Baumann, Hannes. “Social Protest and the Political Economy of Sectarianism in Lebanon.” Global Discourse 6, no. 4 (October 1, 2016): 634–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2016.1253275.Baumann, Hannes. “The Causes, Nature, and Effect of the Current Crisis of Lebanese Capitalism.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 25, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2019.1565178.

Bøås, Morten, and Kathleen M. Jennings. “Insecurity and Development: The Rhetoric of the ‘Failed State.’” The European Journal of Development Research 17, no. 3 (July 1, 2005): 385–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810500209148.

Brown, Graham, Arnim Langer, and Frances Stewart. “A Typology of Post-Conflict Environments: An Overview.” CRISE Working Paper. Center for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, December 2008.

Brown, Richard H. “Reconstructing Infrastructure.” In Postconflict Development: Meeting New Challenges, edited by Gerd Junne and Willemijn Verkoren, New ed. edition. Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Pub, 2004.

Brubaker, Rogers. “Religious Dimensions of Political Conflict and Violence.” Sociological Theory 33, no. 1 (March 1, 2015): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275115572153.

Cammett, Melani. “Lebanon, the Sectarian Identity Test Lab.” The Century Foundation, April 10, 2019. https://tcf.org/content/report/lebanon-sectarian-identity-test-lab/.

Cammett, Melani. “Sectarianism and the Ambiguities of Welfare in Lebanon.” Current Anthropology 56, no. S11 (2015): S76–87. https://doi.org/10.1086/682391.

Carpi, Estella. “Prisms of Political Violence, ‘Jihads’ and Survival in Lebanon’s Tripoli.” Civil Society Knowledge Centre 1 (December 1, 2015). https://doi.org/10.28943/CSKC.003.300011.

CCAVT. “Al-Nushra al-Awwal: Āb 23 Ṭrablus «sanabqā Mutahadyn».” Coalition of Campaigns Against Violence in Tripoli, 2013. http://www.tripolicoalition.org/newsletter/Tripoli_Coalition_Newsletter.pdf.

Chaaban, Jad. “I’ve Got the Power: Mapping Connections between Lebanon’s Banking Sector and the Ruling Class.” In Crony Capitalism in the Middle East, 330–43. Oxford University Press, 2019. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198799870.001.0001/oso-9780198799870-chapter-13.

Christophersen, Mona. “Pursuing Sustainable Development under Sectarianism in Lebanon.” International Peace Institute (blog), April 3, 2018. https://www.ipinst.org/2018/04/pursuing-sustainable-development-under-sectarianism-in-lebanon.

Cornish, Chloe. “Billionaires and Bankrupts: Lebanon’s Second City Highlights Inequality.” Financial Times, October 5, 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/049f55e5-061f-4f8b-9d44-1aff71916f98.

Cramer, Christopher. Civil War Is Not a Stupid Thing: Accounting for Violence in Developing Countries. London: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 2006.

Cramer, Christopher. “Does Inequality Cause Conflict?” Journal of International Development 15, no. 4 (2003): 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.992.

Dagher, Stephanie. “Unpacking the Dynamics of Contentious Mobilisations in Lebanon: Between Continuity and Evolution.” Text. Conflict Analysis Project. Civil Society Knowledge Centre, August 23, 2021. https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/unpacking-dynamics-contentious-mobilisations-lebanon-between-continuity-and-evolution.

Dibeh, Ghassan. “The Political Economy of Postwar Reconstruction in Lebanon.” 44. WIDER Working Paper. United Nations University - WIDER, 2005. https://www.wider.unu.edu/publication/political-economy-postwar-reconstruction-lebanon.

Diwan, Ishac, and Jamal Ibrahim Haidar. “Clientelism, Cronyism, and Job Creation in Lebanon.” In Crony Capitalism in the Middle East, 119–45. Oxford University Press, 2019. https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780198799870.001.0001/oso-9780198799870-chapter-5.

El Dahan, Maha, and Laila Bassam. “Lebanon Currency Drops to New Low as Financial Meltdown Deepens.” Reuters, June 13, 2021, sec. Middle East. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/lebanon-currency-drops-new-low-financial-meltdown-deepens-2021-06-13/.

El-Khazen, Farid. The Breakdown of the State in Lebanon, 1967-1976. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Eltahir, Nafisa. “UNICEF Warns Millions of Lebanese Face Water Shortages.” Reuters, August 21, 2021, sec. Middle East. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/unicef-warns-millions-lebanese-face-water-shortages-2021-08-21/.

Eltahir, Nafisa, and Issam Abdallah. “Life Grinds to a Halt in Lebanon’s Blackouts.” Reuters, August 13, 2021, sec. Middle East. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/life-grinds-halt-lebanons-blackouts-2021-08-13/.

Fregonese, Sara. “Beyond the ‘Weak State’: Hybrid Sovereignties in Beirut.” ENVIRONMENT AND PLANNING D-SOCIETY & SPACE 30, no. 4 (2012): 655–74. https://doi.org/10.1068/d11410.

Gade, Tine. “Sunni Islamists in Tripoli and the Asad Regime 1966-2014.” The View From Without: Syria & Its Neighbours, Syria Studies, 7, no. 2 (2015). https://ojs.st-andrews.ac.uk/index.php/syria/issue/view/116.Gaspard, Toufic. “Financial Crisis in Lebanon.” Policy Paper. Maison du Futur & Konrad Adenauer Sif

tung, August 2017.

Ghosn, Faten, and Sarah E. Parkinson. “‘Finding’ Sectarianism and Strife in Lebanon.” PS: Political Science & Politics 52, no. 3 (July 2019): 494–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000143.

Haddad, Fanar. “‘Sectarianism’ and Its Discontents in the Study of the Middle East.” The Middle East Journal 71, no. 3 (August 1, 2017): 363–82. https://doi.org/10.3751/71.3.12.

Hall, Richard. “A Lebanese City Once Blighted by Extremism Has Become the Unlikely Focus of Nationwide Protests.” The Independent, December 16, 2019, sec. News. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/lebanon-protests-riots-tripoli-hezbollah-whatsapp-a9170611.html.

Hazbun, Waleed. “Assembling Security in a ‘Weak State:’ The Contentious Politics of Plural Governance in Lebanon since 2005.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 6 (June 2016): 1053–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1110016.

Hermez, Sami. War Is Coming: Between Past and Future Violence in Lebanon. Ethnography of Political Violence. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017. https://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/15646.html.

Höckel, Kathrin. “Beyond Beirut: Why Reconstruction in Lebanon Did Not Contribute to State-Making and Stability.” Occasional Paper. London School of Economics and Political Science: Crisis States Research Centre, 2007.

Ibrahim, Alia, Nawaf Kabbara, Khaled Ziadeh, Jamil Mouawad, Jana Dhaiby, Mustafa Al-Aweek, Samer Hajjar, and Darine Helwe. “Is There a Tripoli Exception?” Webinar, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Middle East Center, February 22, 2021. https://carnegie-mec.org/2021/02/22/is-there-tripoli-exception-event-7546.

Junne, Gerd, and Willemijn Verkoren, eds. Postconflict Development: Meeting New Challenges. New ed. edition. Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Pub, 2004.

Justino, Patricia, Tilman Brück, and Philip Verwimp, eds. A Micro-Level Perspective on the Dynamics of Conflict, Violence, and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199664597.001.0001.

Khalaf, Samir. Civil and Uncivil Violence in Lebanon: A History of the Internationalization of Communal Conflict. Columbia University Press, 2002.

Knecht, Eric, and Yara Abi Nader. “In Lebanon’s Sweeping Protests, Hard-Hit Tripoli Sets the Tempo.” Reuters, November 4, 2019, sec. Emerging Markets. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-lebanon-protests-tripoli-idUSKBN1XE13J.

Knudsen, Are John. “Patrolling a Proxy War: Citizens, Soldiers and Zuʻama in Syria Street, Tripoli.” In Civil-Military Relations in Lebanon: Conflict, Cohesion and Confessionalism in a Divided Society, edited by Are John Knudsen and Tine Gade. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55167-8.

Knudsen, Are John, and Nasser Yassin. “Political Violence in Post-Civil War Lebanon.” In The Peace In Between: Post-War Violence and Peacebuilding. Routledge, 2013.

Kortam, Marie. “Tripoli dans le marécage syrien.” revue ¿ Interrogations ?, no. 24. Public, non-public: questions de méthodologie (June 2, 2017). http://www.revue-interrogations.org/Tripoli-dans-le-marecage-syrien,575.

Kosmatopoulos, Nikolas. “Toward an Anthropology of ‘State Failure’: Lebanon’s Leviathan and Peace Expertise.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice, no. 3 (2011): 115. https://doi.org/10.3167/sa.2011.550307.

Langer, Arnim, Frances Stewart, and Rajesh Venugopal. “Horizontal Inequalities and Post-Conflict Development: Laying the Foundations for Durable Peace.” In Horizontal Inequalities and Post-Conflict Development, edited by Arnim Langer, Frances Stewart, and Rajesh Venugopal, 1–27. Conflict, Inequality and Ethnicity. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230348622_1.

Larkin, Craig, and Olivia Midha. “The Alawis of Tripoli: Identity, Violence and Urban Geopolitics.” In The Alawis of Syria: War, Faith and Politics in the Levant, 181–206. C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 2015. https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/the-alawis-of-tripoli(b7e65285-298a-468f-9bde-825ec4a93110).html.

Leenders, Reinoud. Spoils of Truce: Corruption and State-Building in Postwar Lebanon. 1st ed. Cornell University Press, 2012. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.cttq438h.

Lefèvre, Raphaël. “The Roots of Crisis in Northern Lebanon.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 2014.

Mac Ginty, Roger. “Complementarity and Interdisciplinarity in Peace and Conflict Studies.” Journal of Global Security Studies 4, no. 2 (April 1, 2019): 267–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogz002.

Mac Ginty, Roger. “Reconstructing Post-War Lebanon: A Challenge to the Liberal Peace?” Conflict, Security & Development 7, no. 3 (October 1, 2007): 457–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678800701556552.

Mac Ginty, Roger, and Christine Sylva Hamieh. “Made in Lebanon: Local Participation and Indigenous Responses to Development and Post-War Reconstruction.” Civil Wars 12, no. 1–2 (January 1, 2010): 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2010.484898.

Mac Ginty, Roger, and Andrew Williams. Conflict and Development. 1st edition. London ; New York: Routledge, 2009.

Makdisi, Samir A. The Lessons of Lebanon: The Economics of War and Development. London; New York: I.B. Tauris, 2004. http://www.dawsonera.com/depp/reader/protected/external/AbstractView/S9786000007829.

Makdisi, Ussama. The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. University of California Press, 2000.

Melber, Henning, ed. “Development Dialogue No 58: The End of the Development-Security Nexus? The Rise of Global Disaster Management.” Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, no. 58 (April 2012). https://www.daghammarskjold.se/publication/end-development-security-nexus-rise-global-disaster-management/.

Micocci, Fabiano. “Envisioning a Post-Conflict Tripoli: The Inclusive Urban Strategy and Action Plan for Bab Al-Tabbaneh and Jebel Mohsen.” FOOTPRINT, 2016, 57–78. https://doi.org/10.7480/footprint.10.2.1160.

Mikdashi, Maya. “What Is Political Sectarianism?” Jadaliyya - جدلية, March 25, 2011. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/23833.

Milligan, Margaret. “Tripoli’s Troubles to Come.” Middle East Research and Information Project, August 10, 2012. https://merip.org/2012/08/tripolis-troubles-to-come/.

Nahas, Charbel, and Maha Yahya. “Stakeholder Analysis and Social Assessment for the Proposed Cultural Heritage and Tourism Development Project.” Information International SAL, November 2001.

O’Gorman. Conflict and Development. London, UNITED KINGDOM: Zed Books, Limited, 2011. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/soas-ebooks/detail.action?docID=738305.

Osoegawa, Taku. Syria and Lebanon : International Relations and Diplomacy in the Middle East. I.B. Tauris, 2013.

Parreira, Christiana, and Kelly Stedem. “Lebanese Are Protesting in All Regions of the Country, Not Just Beirut. Here’s Why That Matters.” Washington Post, October 24, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/10/24/lebanese-are-protesting-all-regions-country-not-just-beirut-heres-why-that-matters/.

Peace Labs. “Peace Labs - About Us.” Accessed September 6, 2021. https://peace-labs.org/en/about-us/.

Pouligny, Beatrice. Peace Operations Seen from Below: U.N. Missions and Local People. London: C. Hurst & Co, 2005.

Reilly, James. “Ottoman Tripoli in Recent Lebanese Historical Memory.” In In the House of Understanding: Histories in Memory of Kamal S. Salibi. American University of Beirut, 2017. https://www.academia.edu/34241474/Ottoman_Tripoli_in_Recent_Lebanese_Historical_Memory.

Reilly, James A. The Ottoman Cities of Lebanon : Historical Legacy and Identity in the Modern Middle East. London IB Tauris, 2016.

Roy, Sara. 1987. “The Gaza Strip: A Case of Economic De-Development.” Journal of Palestine Studies 17 (1): 56–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/2536651.

Roy, Sara. 1995. The Gaza Strip: The Political Economy of De-Development. Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies.

Roy, Sara. 1999. “De-Development Revisited: Palestinian Economy and Society Since Oslo.” Journal of Palestine Studies 28 (3): 64–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/2538308.