Lebanon 2004 Construction Law: Inside the Parliamentary Debates

The dense state of construction in Beirut is often denounced by researchers, journalists, and activists. The “Concrete Jungle” has become a synonym for the city. However, the development of this “jungle” is regulated by strict laws, in particular, the Construction Law. This paper, largely based on the author’s Masters thesis, offers a behind-the-scenes view of the process of promulgating that law, through examining the relevant parliamentary debates. While advocating the common good, the debates were plainly in favor of the real estate industry, with which the political elite has intricate ties. Moreover, and critically enough, all along these debates, parliamentarians were keen on (re)defining the “correct” aesthetics and ethics for Lebanon’s urban future.

To cite this paper: Hisham Ashkar,"Lebanon 2004 Construction Law: Inside the Parliamentary Debates", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2014-10-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.002.20005

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/lebanon-2004-construction-law-inside-parliamentary-debates

Introduction

Beirut is a city in transformation. Large construction sites extend across the Lebanese capital. Huge construction cranes, towering above various neighborhoods, have become a familiar sight in the urban cityscape, while old roof-tiled houses are completely dwarfed and encircled by new high-rises. The latest Construction Law, No.646,1 passed in 2004, plays an important role in fostering the mushrooming of these high-rises by allowing a higher and larger volume of construction.2 It is no coincidence that the last real-estate boom in Beirut took off around the same time of the promulgation of the Law,3 with many real estate developers putting their projects on hold pending its enactment.4

Moreover, real-estate developers – through their union, Building Promoters Federation of Lebanon (BPFL) – contributed significantly to drafting the 2004 Construction Law5 and "in ways that best fit their own building practices."6 Elie Sawma, the head of the BPFL, even claims that the Law was studied at their office, that they attended the parliamentary meetings, and that they “wrote it and sent it to the parliament and [the Lawmakers] signed it.”7 Sawma’s simplistic narrative not only exaggerates the role of the BPFL, but also narrows down the part played by the parliament to mere ratification. While there is no doubt that the real-estate developers lobby exerts influence and pressure on the Lebanese State and politicians, the parliamentary discussions regarding the Construction Law reveal a very active role of parliamentarians in its shaping.

Perhaps the most significant were the arguments put forth in these debates, as well the parliamentarians’ points of view on the Lebanese administration and their proposals for dealing with certain urban issues.

This article will examine the minutes of five meetings held by the parliamentary joint committees entrusted with finalizing the draft Law, before its approval by the parliament. Nonetheless, it is worthy to note that the new law does not present drastic changes in comparison with the previous law, Legislative Decree No.148/1983, as most amendments were related to the different types of permits, insurance, parking spaces, increase in the exemptions for the exploitation ratios, and stricter rules for the Grands Ensembles.8

The classified documents

It should be mentioned that the minutes under discussion are considered internal parliamentary documents and were not intended for the public. However, in September 2011, and after several requests and visits to the Lebanese Parliament, I was granted access to five of the minutes of meetings. I was allowed access for research purposes; therefore, the names of members of parliament will not be mentioned. Nevertheless, the disclosure of names will not have any major relevance, since no parliamentarian or parliamentary group distinguished themselves in significantly opposing the proposed law. The minutes are handwritten, photocopying them is prohibited and no digital copies exist either.

The joint committees comprise several parliamentary committees, whose fields of interest range from Public Works to Culture and Defense, among others. In the case of the Law of Construction, representatives of several other public bodies were present on consultative grounds. But no representative of any private entity attended those meetings.9

The accessed meeting minutes and the topics of discussions were the following:

Minutes of Meeting No.6/2004 (henceforth MoM1), dated 27/4/2004: Permits for use of the public domain, extension of permits, incomplete construction of buildings and the role of municipalities, the related fees and fines and which authorities entitled to collect them, and safety regulations.

No.69/2004 (MoM2), dated 4/5/2004: Setback off roads, height of apartments, building envelope, setback off rivers, special regulations for people with impairments, safety regulations, exemptions to the exploitation ratio, balconies, underground floors, and insulation for roofs.

No.144/2004 (MoM3), dated 11/5/2004: Exceptions for certain projects, forms and colors of facades, fences, financial guarantee, insurance, and technical audit.

No.154/2004 (MoM4), dated 1/6/2004: Violations to the Law, fines, and penalties.

No.145/2004 (MoM5), dated 8/6/2004: Judicial competence, role of the Higher Council for Urban Planning (HCUP), and parking spaces.

These documents are not the only minutes of meetings. MoM1 started as a continuity of previous meeting; some gaps also exist between the different meeting minutes.

Towards higher constructions

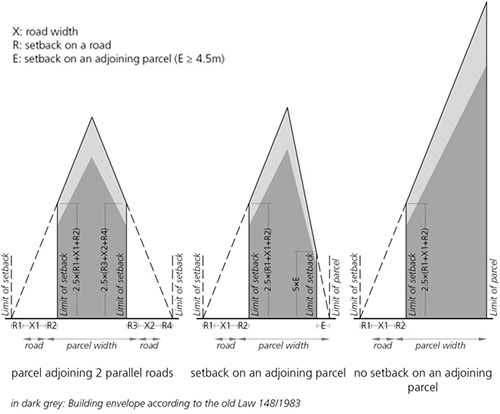

In areas where master plans do not limit the height of constructions, such as most of Beirut, this height is determined by the Law of Construction’s building envelope (the volume inside which the building should be constructed.)

The building envelope according to the Enforcement Decree No.15874/2005. Illustration by author.

The parliamentarians seemed at ease in discussing and debating technical details relating to the envelope. In MoM2, an MP inquired about the issue of setbacks off roads, fearing that they may affect the building envelope, resulting in lower buildings. Clarifications focused on the fact that setbacks will only be set for regions lacking a Master Plan or Zoning. In the discussion, the vertical line of the envelope was calculated as 2×(road+setbacks); high-rise buildings, requiring HCUP approval, remained the ones higher than 40 meters, as in the old law. All the MPs agreed to leave the topic of the envelope to be defined in the Decree following the Law.10 In MoM5, while discussing the issue of parking spaces, it was mentioned that high-rise buildings were the ones that exceed 50 meters.

It is clear that in a meeting between May 4 and June 1, the height of high-rises was increased by 25 percent. The Enforcement Decree No.15874/2005,11 which followed the Law of Construction, confirmed this percentage increase for high-rises and the building envelope as well. While the issue of the envelope and height was not specified in the Law, there was a general agreement towards higher buildings. This tendency is better described in the topic on parking in MoM5: if a high-rise allocated parking spaces for the municipality, it can go higher by two floors. When a member of parliament questioned if these two floors "should be in respect to the [related] Master Plan," there was an accord that "the shape will not change if you add two floors." This height gain comes as a precious gift for developers, as the price of apartments increases by at least US$100 per square meter per floor.12

It is worth noting that the building envelope is one of the main factors affecting the landscape of Beirut. Architects, in their bid to take full advantage of the allowed height, tend more and more to design the top of buildings in a triangular or conical shape.

Buildings under construction in Beirut, with a triangular or conical ending. Architect: Bernard Khoury. Source: bernardkhoury.com

Balconies or rooms?

In the discussion, the drive was not only towards higher buildings, but also for increasing the Total Exploitation Ratio (TER). The TER is the allowed constructible square meters per plot, therefore any increase in the TER means an increase in the profit due to the additional space produced in this plot. The case of balconies represents a clear example for this tendency. In the old Law, balconies were exempted from the TER on condition that their areas do not exceed 20% of the TER. The draft of the new Law proposed that glass curtains to be considered like usual textile curtains. In MoM2, only one Member of Parliament and the director general of Urban Planning objected, arguing that balconies should not be closed spaces, otherwise they will turn into additional living rooms; therefore it is an increase to the TER by 20%. The parliamentarian also argued that glass curtains are very expensive, thus "we will be favoring rich people." The response of his fellows MPs ignored the TER increase worries, and stressed the right to use balconies, and on taking people’s needs and desires into consideration:

“MP1: I, as a citizen, want to take advantage of my balcony. So you allow me to use it in summer but not in winter?”

“MP2: It has been thirty year that people close their balconies, to make new rooms, lack of money do not allow them to buy a new apartment. Nowadays people use less their balconies, because of the pollution and noise.”

“MP3: let us see, within the framework of law, what is that the people desire, and then legislate it.”

What was later concretized is that the adoptions of this clause turned the balconies into de-facto closed spaces, therefore increasing the TER by 20%. In general, the new Law can add more than 30% in comparison to the old Law, nearly doubling the original TER.13

Balconies according to the old (left) and the new (right) Law. Furn el-Hayek Street, Beirut. Image by author. 2011.

HCUP: “politicized” administration and “unconstitutional” powers?

The Higher Council for Urban Planning is the body entrusted with approving plans and regulations elaborated by the Directorate General of Urban Planning, prior to their transfer to the Council of Ministers. Its powers include the authorization of requests for constructing Grands Ensembles and high-rises. In MoM5, the head of the Legislation and Consultations department at the Ministry of Justice considered the latter powers as unconstitutional, since the HCUP is considered a “technical advisory body.” Still, his comments were not taken into consideration by parliamentarians. One deputy, however, after knowing that the HCUP is mainly composed of director-generals, questioned its competence in taking decisions regarding allowing certain constructions or exceptions, as "it is politicized. Because it is known who appointed this director general or that one.” The answers of other members of parliament ranged from “so, should we seek a reference from outside Lebanon?” to “maybe we should check on Mars.” The notes showed that the session continued in a light humor tone. None of the present director-generals commented. Parliamentarians not only disregarded the opinion of a judicial body, they also acknowledged that the HCUP serves best the interests of politicians, therefore following these interests over those of the public interest.

The “civilized” way

Throughout the debates, parliamentarians were keen on backing their arguments with what “people need and desire,” as was shown previously in the debate on balconies. They insisted on proposing a law that "could be implemented," as illustrated by this excerpt from the discussion on parking, in MoM5:

"There is no institution or restaurant in Beirut that abides by the Law; we want to find a text, so we can, after the ratification of this law, ask the Ministry of Tourism to enforce the Law [...] we do not change the law, which suspends it, but rather find a solution through which to enforce the Law.”

However, they did not refer once to a study or any other telling information on the extent of law violations, nor on people’s needs and desires. Paradoxically, when it came to aesthetics, the tone changed. In MoM3, there was a general agreement that the “forms and colors of façades have to be harmonious with the surroundings.” However, the Construction Law does not deal with these directives and details. Rather, this is the role of Master Plans. Nonetheless, the clause on balconies represents an exception, since it homogenized the texture used to cover them: transparent non-colored glass. On this issue, harmonization became homogenization. Moreover, parliamentarians considered it as their duty to set people’s needs and desires within the framework of what is accepted aesthetically and what is considered civilized, as is expressed best by these words:

"People use different colors for their curtains; it is a distortion for the exterior look of the building. Glass represents aesthetics. […] Let us regulate in a way to preserve a homogeneous appearance [...] let us see, within the framework of law, what the people desire, and then legislate it [...] at least we will be giving them opportunities to close their balconies in a civilized way."

No parliamentarian put in doubt this narrative on the "correct" aesthetics for society, nor if it is their duty to establish what is civilized or not. The most telling responses were tacit agreements, such as:

"What is the difference between a textile curtain and a glass curtain? We suggest the use of transparent not-colored glass."

This mixture of pedagogical and patriarchal approach was present more or less in all the debates. While the reference to people’s needs and desires was brought up mainly on issues leading to an increase in the exploitation ratios.

The ratification of the Law: “unanimous” is the keyword

The minutes of the parliamentary general sessions (open to the public), consulted at the library of the parliament, depicts the process of promulgation of the Construction Law. In a parliamentary session on December 11, 2004, the speaker of the parliament proposed that the law be ratified as one article, hence excluding thorough debate. Any chance of debate was also eliminated when he suggested that this law should be treated in urgency. The parliament backed this suggestion unanimously and the law was put to vote and ratified unanimously as well.

The political elite and the real-estate industry

The outcome of the joint committees’ debates, as well as the quick and unanimous ratification of the law, can be best assessed through exploring the ties between the Lebanese political elite and the real-estate industry.

Frequently, researchers and experts have pointed out that many politicians are involved in real-estate.14 Usually, former prime minister Rafik Hariri has been cited as the main example of politician-developer, and to a lesser degree Michel Murr, a current MP and former minister.15 However, a study showing the extent of involvement of the political elite in real-estate is still lacking. Nevertheless, three types of relations can be identified: a direct one (comprising mainly politician-developers), an indirect one (politicians who invest in companies that in turn invest in real-estate), and hidden-direct (politicians investing in real-estate as silent associates, in an informal way and unknown to the general public). Hariri and Murr are the main icons of the first group.

Hariri was a real-estate mogul, but he also involved his inner circle in his business. Najah Wakim lists over fifty real-estate companies owned by Hariri’s close associates. Among them: Bahiya Hariri, current MP; Fouad Siniora, current MP and former prime minister; Joseph Moughaizel, former MP; Bahij Tabbara, former MP. Rafic Hariri real-estate companies were inherited by his children, one of whom is Saad Hariri, current MP and former prime minister.16

Outside of the Hariri circle, the list grows longer. Beside Michel Murr, we can identify:

Samir Mokbel, the current Deputy Prime Minister of Lebanon, is a real-estate developer by profession. His company, S.Mokbel & Partners,17 has been involved in real-estate development since 1965. Michel Pharaon, current MP and former minister, is the CEO of Pharaon Holding sal,18 owner of the real-estate company Polygon sal.19 Mohammad Safadi, current MP and minister, built his fortune in the real-estate sector in Saudi Arabia20 and owns Stow Capital Partners Limited.21 Ghazi Aridi, current MP and minister, is a real estate investor,22 and his son owns ACEC sarl.23 Current MP and former minister Yassine Jaber's brother Rabah is chairman and CEO of Jaber Group,24 established by their father in the 1950s. Current MP Ibrahim Kanaan's brother is CEO of Comptoir el-Amaneh,25 established by their father in 1959.

For the second type of relations, a good example is Najib Mikati, fomrer prime minister and MP. As part of his large financial empire, Mikati and his brother own 7.9% of Bank Audi shares,26 through two of their companies.27 Bank Audi, as most banks in Lebanon, invests heavily in real-estate; it even has its own real-estate company.28 Bank Audi also owns around 4.7 million shares in Solidere. Following the trail of shareholders, especially the banks, can uncover more of this intricate network. For example, Rabah Jaber is member of the board of directors of the banking group Crédit Libanais. Also present on the board is Marwan Hamade, current MP and former minister, and Sarkis Demerdjian, former MP. Crédit Libanais owns two real-estate companies: Cedar’s Real Estate sal and Capital Real Estate sal.29

Nevertheless, the bulk of the political elite prefer to invest as silent associates. In an interview in 2011, the economic journalist Mohamad Wehbe named several politicians who prefer this way of action. The top four of his list for investment in Beirut were Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri, current MP and former minister Walid Jumblat, former prime minister Najib Miqati, and Michel Pharaon.30

Conclusion

In sum, an overwhelming majority of the Lebanese politico-economic elite who enact laws also invest heavily in real-estate. The anticipated outcome of this conflict of interests is a Construction Law that maximizes the permitted land development, hence increasing the financial profit resulting from this growth in space production. This might not come as a surprise to many Lebanese, but what is further revealing is that parliamentarians assumed the responsibility to define and delineate the correct ethics and aesthetics, to embark on a civilizing mission. These issues and others mentioned in this piece (such as the lack of a scientific approach, or the disregard of the opinion of a judicial body when it does not suit their interests) prompt us to question the process of producing laws. Nowadays it is up to a hundred or so elected officials to determine the shape of the future for more than four million people, through the laws they enact and which are drafted within the scope of interest of specific groups of actors and with a clear lack of scientific or relevant studies and information. It could be time to call for wider participation of concerned parties, to demand a more inquisitive and analytical approach and to envision a different legislation-making process.

Bibliography:

Hicham el-Achkar, 2011, The role of the State in initiating gentrification: the case of the neighbourhood of Achrafieh in Beirut, Master Thesis, Lebanese University, Beirut.

Hicham el-Achkar, July 5, 2012, “The Lebanese State as Initiator of Gentrification in Achrafieh,” Les Carnets de l’IFPO.

Asharq al-Awsat, April 5, 2003, “Lubnan: Tujjar wa ’Iqariyun Yuwakibun Masirat Tahdith al-Tashri’at li-Tahfeez al-Istismar al-’Iqari [Real-Estate Builders and Traders Put on hold their Projects in Anticipation of the Promulgation of the new Law of Construction in Lebanon]”.

Asharq al-Awsat, August 23, 2003, “Tujjar wa Munshi‘ou Abniyah Yatarayasun bi-Mashari’ihom Intizaran li-Sudur Qanun al-Bina‘ al-Jadid fi Lubnan [Lebanon: Real-Estate Entrepreneurs Are Accompanying the Process of Updating Legislation to Stimulate Real-Estate Investment]”.

Karah Byrns, April 2011, “Beirut: Under Destruction”, Executive Magazine, No.141, pp.86-97.

Credit Libanais, 2012, Annual report 2012: Rising Above the Challenges.

Roula Ibrahim, April 18, 2013, “Ghazi Aridi: Lebanese MP Falls From Jumblatt’s Favor,” Al-Akhbar English.

Marieke Krijnen, 2010, Facilitating real estate development in Beirut: a peculiar case of neoliberal public policy, Master Thesis, American University of Beirut, Beirut.

Marieke Krijnen, November 5, 2013, “Filling Every Gap: Real Estate Development in Beirut,” Jadaliyya.

David Leigh and Rob Evans, June 7, 2007, “Biography: Mohammed Safadi,” The Guardian.

Republic of Lebanon, Law of Construction, Legislative Decree No.148/83, November 10, 1983, The Official Gazette, No.45, pp. 1505-1519.

Republic of Lebanon, Law of Construction, Law No.646/2004, December 16, 2004, The Official Gazette, No.66, pp.12007-12034.

Republic of Lebanon, Enforcement Decree of the Law of Construction, Decree No.15874/2005, December 12, 2005, The Official Gazette, No.56, pp. 5857-3932.

Najah Wakim, 2000, Al-Ayadi al-Soud [The Black Hands], Beirut, Sharikat al-Matbou’at lil-Tawzi’ wal-Nashr.

- 1. Law No.646/2004, December 16, 2004, The Official Gazette, No.66, pp.12007-12034. The law can be accessed on this link: http://www.lp.gov.lb/Temp/Files/663b0c63-4584-4654-894b-ee73c0cc9f98.doc (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 2. Hicham el-Achkar, July 5, 2012, “The Lebanese State as Initiator of Gentrification in Achrafieh,” Les Carnets de l’IFPO, http://ifpo.hypotheses.org/3834 (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 3. Hicham el-Achkar, 2011, The role of the State in initiating gentrification: the case of the neighbourhood of Achrafieh in Beirut, Master Thesis, Lebanese University, Beirut, http://hishamashkar.com/node/57 (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 4. “Tujjar wa Munshi‘ou Abniyah Yatarayasun bi-Mashari’ihom Intizaran li-Sudur Qanun al-Bina‘ al-Jadid fi Lubnan, [Real-Estate Builders and Traders Put on hold their Projects in Anticipation of the Promulgation of the new Law of Construction in Lebanon],” August 23, 2003, Asharq al-Awsat, http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8800&article=188753#.VCmfkBY0-FJ (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 5. “Lubnan: Tujjar wa ’Iqariyun Yuwakibun Masirat Tahdith al-Tashri’at li-Tahfeez al-Istismar al-’Iqari [Lebanon: Real-Estate Entrepreneurs Are Accompanying the Process of Updating Legislation to Stimulate Real-Estate Investment],” April 5, 2003, Asharq al-Awsat, http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8800&article=163941#.VCmhEhY0-FJ (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 6. Marieke Krijnen, 2010, Facilitating real estate development in Beirut: a peculiar case of neoliberal public policy, Master Thesis, American University of Beirut, Beirut.

- 7. As cited in Ibid.

- 8. Hicham el-Achkar, 2011, op. cit.

- 9. The joint committees entrusted with finalizing the Law of Construction draft were composed of the following parliamentary committees: Finance and Budget; Administration and Justice; Public Works, Transport, Energy and Water; Defense; Interior and Municipalities; National Education, Higher Education and Culture; National Economy, Trade, Industry and Planning. Also present, on consultative ground: The minister of Public Works; The director general of Urban Planning; The consultant of the minister of Transport; The director general of Roads and Buildings department; The consultant of the minister of Finance; The director general of Antiquities; The director general of Standards and Specifications department; The representative of the Ministry of Interior; The representative of the consultant of the prime minister; The head of the Legislation and Consultations department - Ministry of Justice.

- 10. The Enforcement Decree’s purpose is to determine the conditions of applicability of the Law. Therefore it addresses and develops the details not present in the Law. While producing the Law is the responsibility of the parliament, the Enforcement Decree is the task of the Council of Ministers.

- 11. Enforcement Decree No.15874/2005, December 12, 2005, The Official Gazette, No.56, pp. 5857-3932. The law can be accessed on this link: http://www.oea.org.lb/Arabic/SubWide.aspx?pageid=4290 (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 12. “Pricing,” Trabaud 1804, 2011, http://trabaud1804.com/trabaud.php?id=8 (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 13. Achkar, 2011, op. cit.

- 14. Karah Byrns, April 2011, “Beirut: Under Destruction”, Executive Magazine, No.141, pp.86-97.

- 15. Marieke Krijnen, November 5, 2013, “Filling Every Gap: Real Estate Development in Beirut,” Jadaliyya, http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/14880/filling-every-gap_real-estate-development-in-beiru (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 16. Najah Wakim, 2000, Al-Ayadi al-Soud [The Black Hands], Beirut, Sharikat al-Matbou’at lil-Tawzi’ wal-Nashr.

- 17. “Profile,” S.Mokbel & Partners, http://www.smokbel.com/subpages/page.asp?id=2 (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 18. “Profile - History,” Pharaon Holding s.a.l.; http://www.pharaon.com.lb/profile/index.htm (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 19. “Services - Contracting & Building,” Pharaon Holding s.a.l.; http://www.pharaon.com.lb/services/contracting-building.aspx (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 20. David Leigh and Rob Evans, June 7, 2007, “Biography: Mohammed Safadi,” The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jun/07/bae6 (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 21. “About Us,” Stow, http://www.stowcapitalpartners.com/about-us/about-us.aspx (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 22. Roula Ibrahim, April 18, 2013, “Ghazi Aridi: Lebanese MP Falls From Jumblatt’s Favor,” Al-Akhbar English, http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/15567 (accessed on September 30, 2014)

- 23. “Profile,” ACEC - Aridi Contracting and Engineering Company, http://www.aceclb.com/ (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 24. “About Us,” JABER Group, http://www.jabergrouprealestate.com/ (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 25. CEA real estate’s Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/CEArealestate?sk=info (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 26. “Shareholders,” Bank Audi sal, http://www.banqueaudi.com/CorporateGovernance/Pages/shareholders.aspx (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 27. The two companies in question are Investment and Business Holding sal and MAL Investment One Holding sal.

- 28. CGI - Conseil et Gestion Immobiliere sal’s Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/ConseilEtGestionImmobiliercgi/info (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 29. Credit Libanais, 2012, Annual report 2012: Rising Above the Challenges, http://www.creditlibanais.com.lb/Content/Uploads/AnnualReport/130819015821339.pdf (accessed on September 30, 2014.)

- 30. Interview with Mohamad Wehbe, by Hisham Ashkar, October 17, 2011.

Hisham Ashkar is an architect, urban planner, cartographer, photographer, and investigative researcher. He is currently pursuing a PhD in urbanism at HafenCity Universität-Hamburg, Germany. His dissertation focuses on the changing nature of public space in relation to the gentrification process in Beirut.

Website: hishamashkar.com

Twitter:https://twitter.com/hisham_ashkar