Possibilities and Challenges: Social Protection and COVID-19 Crisis in Jordan

The social protection systems in Jordan face significant challenges, which undermine the country’s ability to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. In fact, this crisis has highlighted the need for economic and financial reform, as the current institutions are not honouring their promises despite the developments in the past decade. Moreover, the crisis has left a tremendous impact on families and communities, including the loss of income and the lack of access to adequate healthcare. The Jordanian government has taken measures to curb the spread of the pandemic but could not establish an effective plan to protect the most vulnerable groups who lack access to advanced social protection systems. The government of Jordan has developed several programmes to cushion the social and economic effects of the pandemic on the most venerable workers in the country. This report describes the different programmes and the mechanisms used to reach the country’s most vulnerable groups. It focuses specifically on informal workers, women, and the youth. The report also shows that Jordan has used its existing social protection systems to reach vulnerable people through emergency cash transfer programmes, either by expanding the already existing programme (Takaful) or creating new ones (Tamkin Iqtisadi, Himaya, Musanid). The Jordanian government’s responsiveness and effectiveness were conditioned and restrictive towards women, informal workers, and refugees. This report analyses the government's response in an attempt to identify gaps in the Jordanian social protection system and how it can be further developed.

To cite this paper: Abdalhadi Alijla,"Possibilities and Challenges: Social Protection and COVID-19 Crisis in Jordan ", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2021-11-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.002.90003

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/possibilities-and-challenges-social-protection-and-covid-19-crisis-jordanIntroduction

The social protection system is an indispensable institution that delivers support to disadvantaged groups in any society. It is an essential process that keeps the community viable and has the capacity to bridge social inequalities. A modern social protection system includes removing barriers to high-quality healthcare, income protection (including for informal workers), job protection, and, finally, preventing vulnerable groups from falling into poverty.

The COVID-19 crisis has worsened the situation in many countries, causing political turmoil. It represented a shock for the fragile political and economic systems, which were already under tremendous pressure (Bartholomew and Diggle 2021), threatening the livelihood and income of millions of people and leading to a rise in poverty levels (WB 2020). In many MENA countries, and despite the weak formal institutions, social protection institutions were at the forefront of governments’ responses to the repercussions of the pandemic.

In Jordan, a resource-poor country suffering from disturbing levels of food insecurity, the lack of energy resources, the ongoing economic crisis, and the Syrian refugee crisis have exacerbated inequalities. Despite the lack of efficient public services (in terms of equality and quality for all) and the economic and financial burden on the Jordanian government, formal institutions were able to provide emergency financial relief through existing formal institutions and newly developed programmes. However, there are fears that the pandemic has been widening the inequality gap between different social segments. In countries like Jordan, where a significant number of workers and families rely on daily wages, there are concerns that these social segments will fall into the trap of poverty as they are not registered into the formal social protection system or protected by any system (Jawad 2020).

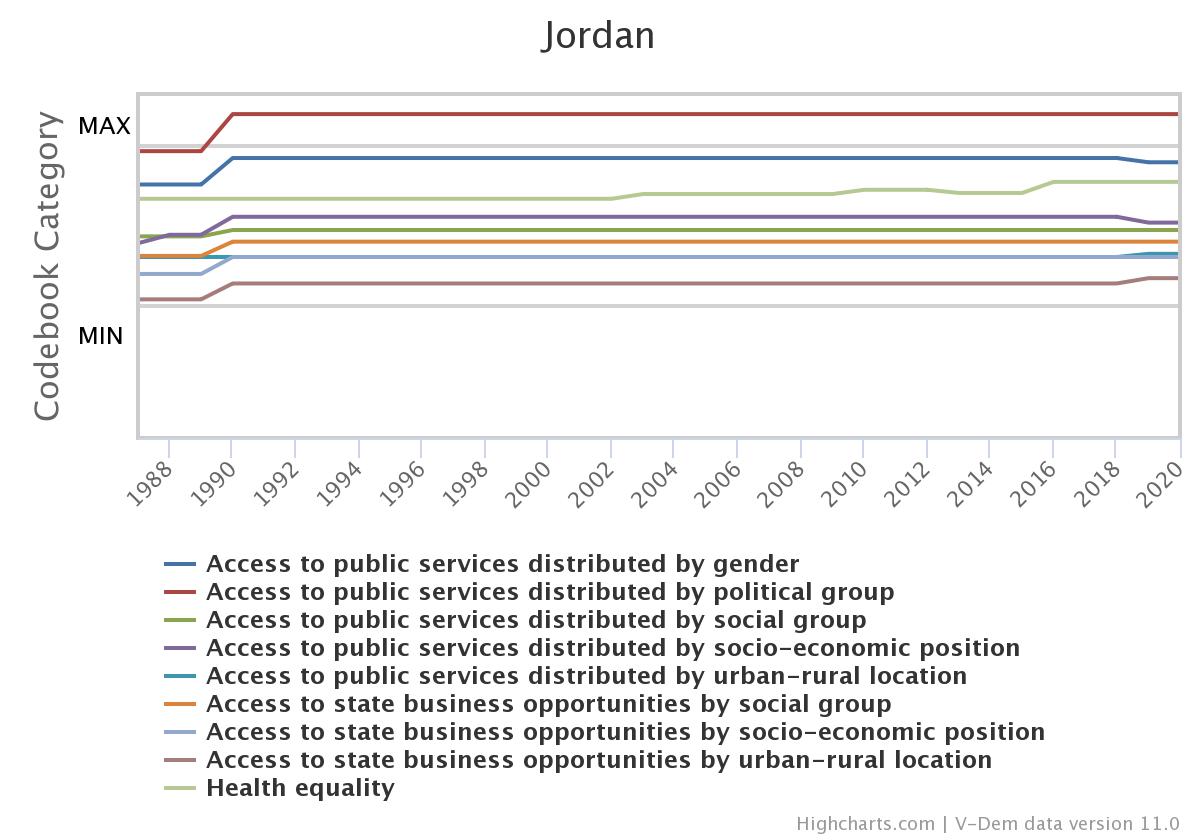

Jordan represents an interesting case study, given the well-established tribal society in the country's peripheries, the high number of informal economy workers, the number of refugees, and the centralized public service system. A tribal society could also provide an informal net of social protection, outside the framework of formal institutions which this report focuses on. Interestingly, Jordanians’ level of access to public services has not changed for the past thirty years. According to data from several democracy institutes, access to basic public services, such as primary schools, water, health, and security, is equally distributed among the population. Quality primary healthcare is also guaranteed for all, and public services are equally distributed based on gender. The above indicators are among the highest in Jordan, compared to other determinants that reveal a pressing problem in Jordan's service provision and social protection system.

Source:V-Dem institute, dataset 11.1 (2021). Created by online tools( www.v-dem.net)

According to V-Dem institute, social groups, socio-economic conditions and area of residence (urban or rural) severely affect the accessibility of public health services. The urban-rural divide plays a significant role in determining whether a person can receive public services or not and represents a significant gap in access to public services, including social protection services, in Jordan. Data from the Arab Barometer published in 2021 indicates that the COVID-19 crisis has had a more harmful impact on people living in rural areas. According to the data, 43% believe that the pandemic has had a more adverse impact in rural areas, while 27.6% believe that the impact was similar in both rural and urban areas.

The pandemic and its repercussions on the Jordanian economy, particularly informal workers, have revealed that the latter are the most vulnerable among at-risk groups. However, Jordan suffers from severe inequality in public employment opportunities and the labour market. According to the AB datasets 2018, 79 per cent of the Jordanians believe that it often needs a “wasta” to get a job in the public sector. According to the World Bank, Jordan’s labour market has been slowly worsening over the past decade. It has one of the lowest levels of labour force participation globally, and only a third of the workforce in Jordan is actually working (Winkler and Alvaro 2019).

The V-Dem data reveals that in the last three decades, access to public employment opportunities has been restricted by socio-economic factors and the urban/rural divide (V-Dem 2021). In general, Jordan has long had inequalities in access to essential services and economic opportunities, which affected, according to a Jordanian researcher, its ability to face the financial crisis and later the pandemic, thus exacerbating the situation in the country in general (Researcher A 2021).

The purpose of this research paper is to assess and document the effect of the COVID-19 crisis and the measures taken to counter and mitigate its impact. Such an assessment would help formulate and design the policy tools required for short-term and long-term impacts. The research is desk-based, with qualitative data and quantitative data provided by the Arab Barometer from 2020 and 2021 (AB 2021b).

Crises and Vulnerabilities

Jordan's geographical location has taken a toll on its stability, since its economy and ability to face challenges are often dictated by the political situation in the region. The civil war in Syria, the disruption of the gas pipeline in Egypt, the Iraq crisis, the Palestinian cause, and the decreasing funds from the Gulf have affected Jordan's socio-economic and political situation. The government's ability to provide high-quality services was undermined to a certain extent, and many businesses and development programmes, including social protection programmes, were disrupted (Tuimat 2020). Additionally, Jordan's population grew rapidly in the last decade due to the influx of Syrian refugees. As of 2021, the UNHCR reports more than 663,000 Syrian refugees officially registered in Jordan. Other figures indicate that the number of informal refugees who live in host communities and receive services equals the officially registered figures (UNHCR 2019).

As of the 6th of October 2021, the Jordanian Ministry of Health (MoH) reported 739,847 cumulative cases of COVID-19, with 9,530 deaths (JMOH 2021). As the first wave of the pandemic hit the country, the government of Jordan, with the King’s support, activated the National Defence Law No. 13 (1992), which imposes a state of emergency, lockdown, curfew, and closure of borders, while giving the military more power (HRW 2020). Since then, defence orders have occasionally been issued to contain the spread of the virus. Cases began to increase after the government made the decision to open the country and lift restrictions. A few months after the restrictions were imposed, strong opposition from the population arose, especially those who had lost their income due to these restrictions.

Source : WDI, Macro Poverty Outlook, and official data.

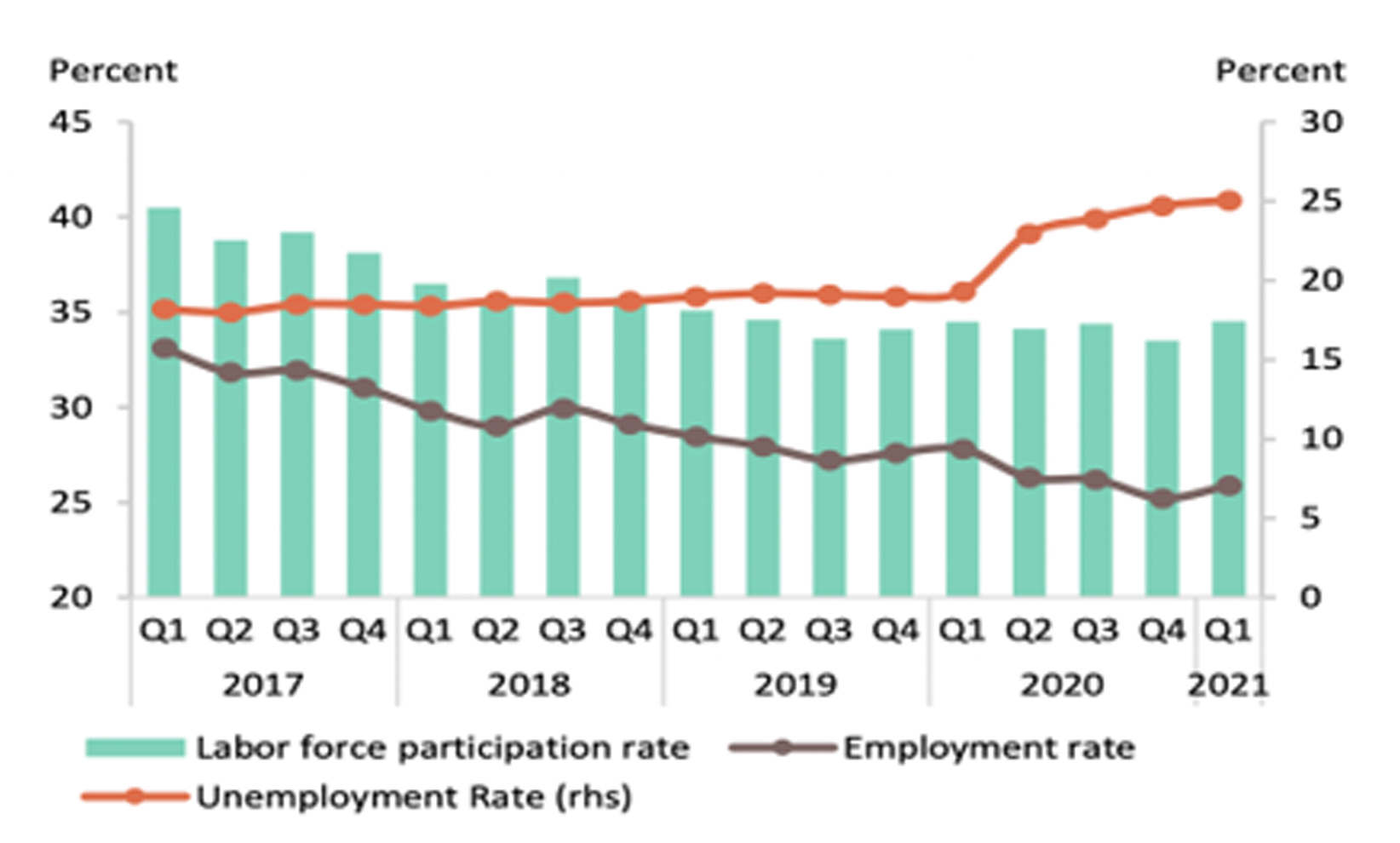

Although Jordan is a middle-income country, poverty rates have been rising due to the economic crisis that has been affecting the country since 2018 and that was exacerbated by the pandemic. Poverty rates were estimated at 13.3% in 2008, 14.4% in 2020, and 20% in 2016 according to unofficial data (MEMO 2019). In early 2020, at the onset of the pandemic, the Jordan Response Plan reported a poverty rate of 15.7%. The high level of poverty was driven by high unemployment rates and the shrinking labour market, which did not meet the population’s needs (JRP 2020). A few months after the pandemic and the subsequent lockdown in Jordan, the poverty rate rose sharply. The poverty rate in the second half of 2020 reached 26%, and the unemployment rate reached 24.7% (Figure 1 and 2)

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 2 Sources: Department of Statistics and World Bank staff calculations.

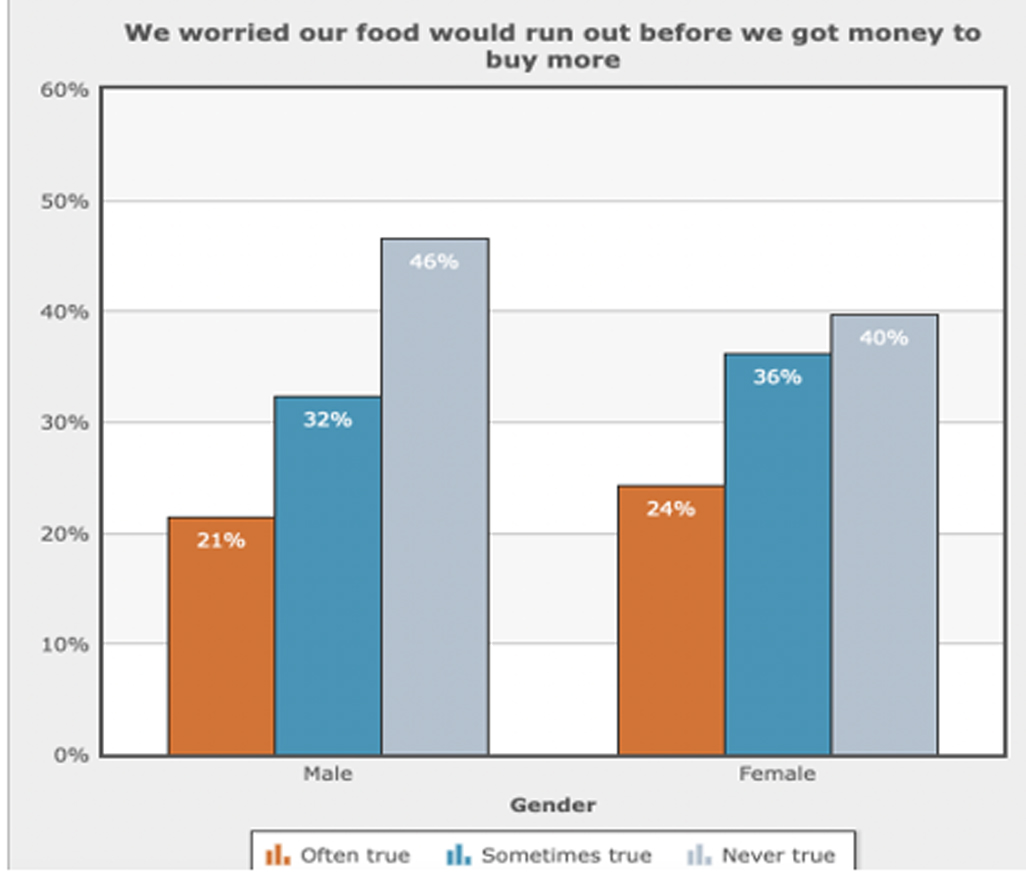

Overall, the effect of COVID-19 on women was devastating compared to men. Aside from the increased violence against women, in Jordan, female unemployment rose at a higher rate than that of the general population, jumping from 24.3% at the beginning of 2020 to more than 32% by the end of 2020 and the beginning of 2021 (UNDP 2021). This finding is a clear indicator of the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on women, who express more concern about their ability to provide enough food for their families compared to men.

Figure SEQ Figure \* ARABIC 3 We worried our food would run out before we got money to buy more

According to the Arab Barometer 2021 survey, 24% of women said that it is often true they worry that their food would not be enough of the next days compared to 21% of men, while more than 36% of women said it is sometimes true that they worry that food will not be sufficient for the next days compared to 32% of men (Figure 2) (AB 2021b).

Before the COVID-19 crisis, social protection programmes supported around 300,000 Jordanians who were living just above the poverty line and would fall into poverty without government support. The form of support is cash-based, voucher and food assistance (GoJ 2021). Although the government has put in place a few measures to mitigate the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on informal workers, who represent around 47% of Jordan’s workforce, through the National Aid Fund, social protection programmes and others, this report shows concerning evidence that only a fraction of these measures reached vulnerable groups in the country. This exposes a gap in targeting informal workers and vulnerable groups. The inability of the government to reach informal workers, who are the most prominent vulnerable group in this crisis, led to a rise in the poverty rate in Jordan. As the pandemic hit Jordan, most Jordanians expressed their concern about the possibility that their family might lose its major source of income (44% very concerned, 21% concerned). This concern is related to the public’s perception of the economic situation in Jordan for many years.

Additionally, Jordan hosts more than 340,000 migrant workers officially registered with the Ministry of Labour, while the International Labour Organization indicates that there are 1.4 million migrant informal workers in the country (Razzaz 2017). The latter face heightened challenges, as they are not covered by the social protection system and lack proper access to high-quality services. According to a Jordanian researcher, many of those workers decided to leave Jordan as the pandemic hit the country and they found themselves unable to meet their needs (Researcher B 2021).

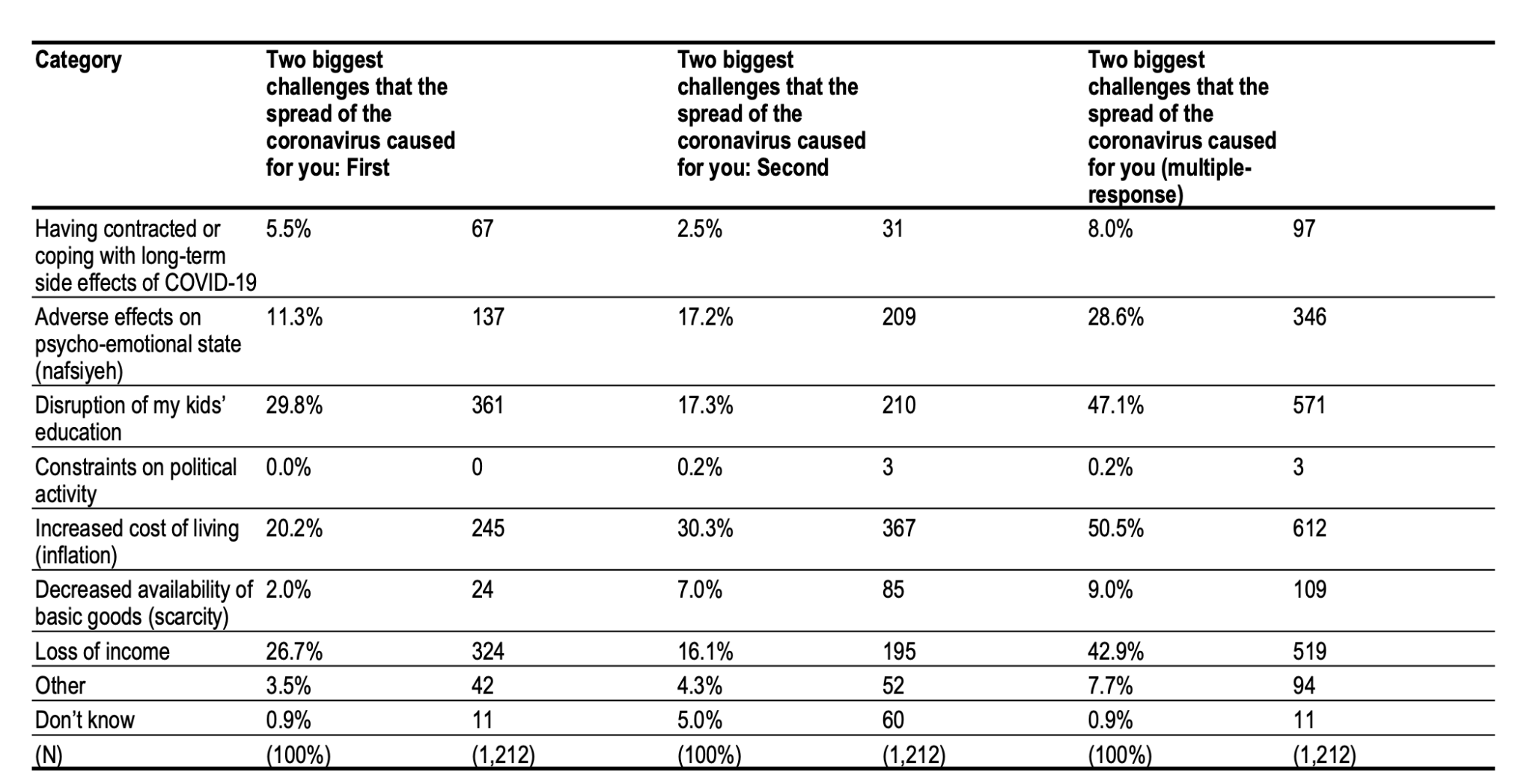

According to the Arab barometer, the main challenges and priorities for the Jordanian population have been economic, poverty and unemployment-related over the past decade. In 2013, more than 57% of the population believed that the economic situation is the main challenge in the country, followed by financial and administrative corruption. In 2019, more than 71% perceived the economic situation, unemployment, and price increases as the main challenges facing Jordanians. Another risk posed by the COVID-19 pandemic is the rising education inequalities in Jordan, especially for the disabled, rural residents, and refugees. Girls are at greater risk of dropping out of school, which may lead to early marriage, while children, in general, suffer from child labour (UNDP 2021). According to UNICEF, more than 150,000 children in Jordan did not attend basic education, risking increased inequality (UNICEF 2021)[1]. These learning disparities indicate that the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the Jordanian government’s unpreparedness to distance learning technology.

Source: Arab Barometer, 2020-2021.

As such, the post-pandemic challenge will be to bridge the educational gap for these children, as educational disparities will affect the post-pandemic training opportunities and well-being of children and the youth. Around 30% of respondents believe that the disruption of their kids’ education is the most alarming concern during the pandemic and a primary challenge, while 17.3% believe that this challenge comes second. Interestingly, 47% perceived the disruption of their kids’ education as a challenge. These figures reflect the concern among Jordanians for the future of their children and the government’s ability to provide the necessary tools to bridge any gap in the future or during the COVID-19 crisis.

Responsiveness and Gaps

Jordan’s National Social Protection Strategy 2019-2025 consists of three main pillars: opportunity, dignity, and Tamkeen.[2] In these three pillars, the focus is to provide decent work and social security, social assistance and social service. As part of the strategy, the GoJ established a “Takaful”[3] solidarity cash assistance programme in May 2019 to reach more than 180,000 poor households by 2022 (MOIP 2019).

The Jordanian government has taken crucial measures from the beginning in an attempt to curb the impact of the COVID-19 on the population. As calls for supporting poor families and workers grew since the onset of the crisis and lockdown, the government initiated several programmes to ensure cash flow and meet the needs of informal workers and families in need. The formal programmes included IMF-funded programmes and the Jordan Reform Matrix, as well as other programmes based on voluntary contributions. These measures targeted vulnerable groups, according to the government (Abdel Samad 2021).

The Jordanian government, along with the different stakeholders, mainly UN organizations, developed a strategy to protect the people, respond to economic challenges, mitigate the loss of income of the most vulnerable groups and protect and support the healthcare system. The strategy aimed at addressing the long- and medium-term effects of COVID-19 on the population, while providing life-saving humanitarian assistance to vulnerable groups who fell into poverty due to loss of income and protecting the healthcare system from collapse (GoJ 2021).

As soon as the government of Jordan announced measures to contain the virus, it also started responding to calls for protecting the most vulnerable groups, mainly those at risk of losing their source of income and small businesses. One of the first funds to be established targeted the general population and was managed by the government, as part of a special intervention programme funded by the private sector and public donations. The other fund, “Hummat Watan,” was managed by private businessmen and featured donations from the private sector (SPC 2021a; NAF 2021c). Two formal institutions led the government’s response to the pandemic and its impact on vulnerable people: the Social Security Corporation (SSC) and the National Aid Fund (NAF). Both institutions have existed for a long time with well-developed institutional and technological infrastructures. They offer several permanent programmes which provide cash and other forms of assistance, such as livelihood and training programmes for the youth and vulnerable groups. However, the main purpose of these programmes is to protect the economy, as the majority of funds targeted formal businesses, neglecting informal workers.[4][5]

The Social Security Corporation, the only public social protection institution in Jordan, responded to the COVID-19 crisis from the beginning, in cooperation with the government. As per the Defence Law No. (13) and Defence Order No. (1) of 2020, the SSC exceptionally deactivated its Social Protection Law. From March 2020, the SSC suspended the deduction of insurance contributions from the private sector, which meant that more than 470,000 individuals in the private sector did not pay their share. The purpose of the decision was to lift some of the financial burdens for the private sector amid the lockdown and the cessation of their activities. The SSC set up several programmes to support the elderly and day labourers with in-kind food parcels. In cooperation with the National Aid Fund, the Military and other institutions, the SSC distributed more than 23,000 food parcels and around 120,000 coupons in the first year of the pandemic (SSC 2021b). A few weeks after the onset of the crisis, the SSC launched five new programmes to protect workers and private enterprises; two of these programmes aimed at protecting private enterprises from collapse, and another three at protecting insured workers. In all five programmes (Table 2), informal workers were not covered and were left behind, despite being at the risk of falling into poverty with their families. Table 2 explain the different programmes initiated by the SSC in Jordan

Table 2 SSC’s programmes during COVID-19 crisis

|

Program |

Description |

No. of Beneficiaries |

Support (Informal Workers) |

Support (Women) |

|

Tadamun 1 |

It targets workers and enterprises who have 12 months of membership payments with the SSC and enterprises covered by SSC. It offers one-time minimum and maximum payments of 156 JD and 500 JD respectively. The total costs of this programme are estimated at 33 million JD. |

91,000 workers (99% Jordanians) |

No |

30% of the beneficiaries are women |

|

Tadamun 2 |

It targets enterprises that are not members of the SSC and employees who have less than 12 months of membership contributions with the SSC. This programme requires the employers to pay 140 JD and pledge to enrol their employees in the SSC as of 2021. The maximum payment for beneficiaries is 300 JD paid twice. The total cost of this programme is at 3.19 million JD. |

13,685 workers (98% Jordanians) |

No |

51% of beneficiaries are women |

|

Musanid 1 |

It targets workers covered by the SSC who lost their jobs or could not work due to the COVID-19 defence law (1/2020). It offers minimum and maximum payments of 150 JD and 350 JD respectively over the course of three months. The total cost of this programme is at 14.7 million JD. |

74,000 workers (99.8% Jordanians) |

No |

23% of beneficiaries are women |

|

Musanid 2 |

This programme allowed non-Jordanians and Jordanians to withdraw a maximum amount of 450 JD for one time from their SSC savings. The total cost of this programme is 27.4 million JD |

319,000 individuals (60% Jordanians) |

No |

34% of the beneficiaries are women |

|

Musanid 3 |

This programme allowed employees covered partially by the SSC with a minimum of 12 months of contributions to take an advance from their account with a maximum of 450 JD over three months. The total cost of this programme is estimated at 46.3 million JD. |

393,000 individuals (98% Jordanians) |

No |

19% of the beneficiaries are women |

|

Himaya |

This programme is designed to support workers and enterprises in the tourism and transport industry. The programme covered 50% of employees’ salaries (paid by the SSC), on the condition that the employer cover 20% of the payment. Payments ranged between 220-400 JD over six months in 2020. The total cost of this programme is 12 million JD. |

11,143 workers (99% Jordanians) |

NO |

14% of the beneficiaries are women |

|

Tamkin Iqtisadi 1 |

This programme is designed to lift some of the burdens off enterprises by allowing them to partially pay the end-of-service indemnity monthly contribution. This programme also aimed to increase the social security net coverage by encouraging employers through financial incentives. |

More than 230,000 workers and 1,552 enterprises |

No |

30% of the beneficiaries are women |

|

Tamkin Iqtisadi 2 |

This programme is intended to allow non-Jordanians, Gazans (who live in Jordan) and employees with Jordanian mothers (non-Jordanians) to apply for an advance payment. |

244,568 workers (97% Jordanians) |

No |

19% of the beneficiaries are women |

Through 2020 and 2021, the SSC changed its programmes and guidelines based on the government’s plan and decrees. As the table shows, informal workers were not covered by any of the SSC’s programmes. Women and the youth were not also targeted or called/encouraged to be part of the SSC’s programmes or apply for membership in a designated program, which could be perceived as a gap in the social protection mechanisms and programmes.

The National Aid Fund is an independent institution governed by a board of directors with an annual budget of 141 million USD. It provided cash transfer assistance to more than 55,000 Jordanians before COVID-19. The NAF targets orphans, elderly people, widows, families living below the poverty line, and families with a disabled breadwinner (NAF 2021b). At the onset of the pandemic, the NAF expanded the scope of the “Takaful” programme to include informal workers, female-headed households (4%) and families who lost their income during the COVID-19 crisis (GoJ 2021). The Takaful programme was expanded in 2019 to provide beneficiaries with health insurance, transportation allowance, energy-saving support, and school meals.

The Takaful programme supported around 180,000 households, in addition to the existing 55,000 beneficiaries. It offered 70 JD for households of 1-2 members and 136 JD for families with more than three members. Through the Takaful program, the NAF assisted more than 250,000 households in 2020 and 160,000 in 2021. According to the NAF, 74,000 households have received support in September 2021, and a new group of beneficiaries will be supported in November 2021 with a total 150 million JD since the beginning of 2021 (Al-Mamlaka 2021d).[6]

The government of Jordan and the Jordanian social protection strategy had a well-prepared infrastructure and cash-assistance and in-kind programmes, which facilitated the expansion and inclusion of new beneficiaries during the pandemic. The diverse programmes, digitization, and shared databases of the National Aid Fund, SSC, and the Ministry of Social Development have widely contributed to the successful management and the fast delivery of cash and in-kind assistance. The implementation, enrolment and payment mechanisms of these cash assistance programmes are entirely digitized, while the data is managed and provided through the National Unified Registry of the population (WB 2021).

Most government programmes were funded either through the IMF, UN, INGOs or the private sector. According to the NAF, the private sector provided 27 million JD through their private fund and donation campaign “Hummat Watan,” supporting the cash transfer programme for 2020 and 2021 (NAF 2021c). In June 2020, the World Bank Group agreed to support Jordan with 374 million USD to face the social and economic challenges caused by COVID-19, supporting 270,000 households. The programme funded by the World Bank was launched in November 2020 and was still ongoing at the time of writing of this report in October 2021 (Takaful 3). In June 2021, the World Bank and IMF approved the disbursement of more than one billion USD under the Extended Fund Facility, supporting economic and financial reforms, while granting more than 100 million USD to NAF’s Takaful programme for 2021 (al-Mamlaka 2021c).

However, according to official data from SSC reports and the Jordanian Government, informal workers have been marginalized. Their need for financial assistance, which could protect them from falling into poverty, has not been sufficiently addressed despite NAF’s various programmes, particularly in light of the increasing cost of living in Jordan.

One question remains unanswered: Who is social protection actually targeting?

Is Social Protection and Reaching Vulnerable Groups?

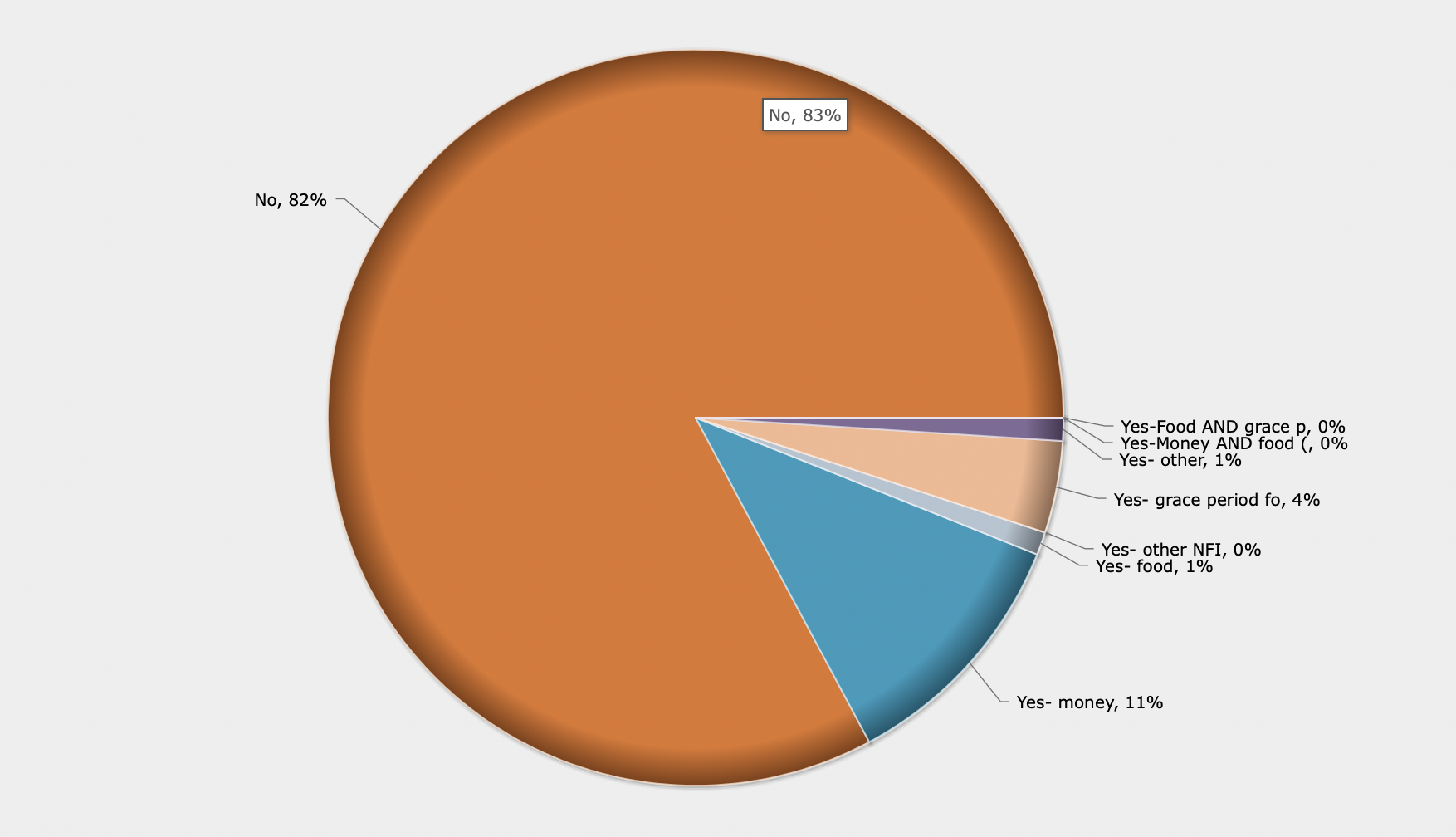

In the same 2018 Arab Barometer survey, 14.8% of respondents considered that the major and most significant challenge facing Jordan is the provision of public services, mainly education, and health (AB 2020).[7] As of April 2021, 9.2% of the surveyed population by AB in Jordan permanently lost their jobs due to the pandemic, while 15.4% lost their jobs temporarily. Only 19.8% stated that the COVID-19 did not affect their job. Nevertheless, more than 53% indicated that the pandemic did not affect their status, as they were already unemployed. According to a labour expert in Jordan, many of those who said they are unemployed are informal workers or daily labourers who work informally on the black market (Researcher C 2021). According to the different programmes of the Jordanian government, SSC and NAF, informal workers were not substantially covered, which is consistent with the data of the Arab Barometer (Figure 4).

Source: Arab Barometer AB 2021.

Although the government has launched new programmes to assist vulnerable groups, findings suggest that many groups have not received any assistance. In April 2021, 76.4% of unemployed respondents surveyed by AB in Jordan stated that they did not receive any relief aid from the government during the pandemic. Similarly, 94.4% of retired persons, 77.7% of self-employed individuals and 82.5% in total said they did not receive any assistance from the government. According to the same survey, only 11.3% received cash-transfer assistance, 0.8% received in-kind food parcels and 0.1% received in-kind material items. The disparity between males and females is also prevalent, as 85% of women said they did not receive any relief assistance from the Government, compared to 79% of men.

In early 2020, before the pandemic, 23% of Jordanians said they were entirely satisfied with the healthcare system, while 53% said they were satisfied. On the other hand, 15% said they were dissatisfied and 8% were entirely dissatisfied (AB 2021b). However, the change in the percentage of Jordanians who are dissatisfied with healthcare in Jordan by the end of 2020 increased. 18% of respondents stated that they were entirely dissatisfied and 14% were dissatisfied. In 2021, the percentage of Jordanians who were not satisfied with the healthcare system grew significantly: 26% of Jordanians said they were not satisfied, while 17% were entirely dissatisfied, 8% (15% in early 2020) entirely satisfied and 49% satisfied (53% in early 2020). These figures reflect a questionable change in the perception of one of the core services in Jordan’s social protection system (healthcare). They either reflect inequalities in access to healthcare during the pandemic or an increasing distrust in the government’s management of the crisis, especially in light of the weaponization of COVID-19 and its mitigation measures. Only 6.6% of respondents believe that Jordan’s healthcare infrastructure can handle the crisis, and only 3.7% believe the Jordanian government’s response to be adequate in stopping the spread of the virus (AB 2021b).

Alarmingly, 34.2% of the Jordanian population believes that the health threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic is exaggerated, which highlights shortcomings in the awareness raising activities carried out by social protection institutions (such as the Ministry of Health, SSC and National Aid Fund). Although the MoH has launched a few campaigns using mainstream and social media, other institutions did not engage widely with the public, despite being in direct contact with the population through their different programmes.

Although Jordan hosts more than 750,000 registered Syrian refugees and more than 89,000 from other countries such as Iraq, Somalia, Yemen, and Sudan, more than 80% of these refugees have no access to livelihood opportunities and are not allowed to work formally in Jordan, which forces them to engage in informal labour to evade living in extreme poverty and to be able to meet their basic needs (IRC 2020). In mid-2020, more than 75% of refugees reported having difficulties in covering basic needs (AB 2021c). While the refugees benefited from basic needs and cash assistance programmes managed by the UNHCR, WFP, UNICEF and several other INGOs, they continue to face difficulties in securing basic needs, as most informal labour has stopped due to the COVID-19 restrictive measures. The data shows that more than 40,000 individuals have benefited from the UNHCR’s COVID-19 cash response programme in 2020 and early 2021 (WFP 2021). In 2020, less than 30 million JD was allocated to protect refugees in Jordan through cash and other in-kind materials (Calp 2021). Likewise, refugees have not benefited from any social security protection programmes managed by the Jordanian government or programmes funded by the IMF and UN and run by the Jordanian government. Despite the lack of government inclusion of refugees, 52% of the population in Jordan believes that the refugees have been more impacted by the pandemic than other groups (AB 2021b).

Although dignity and social security for women are an integral part of the National Social Security Strategy 2019-2015 (MOIP 2019), the COVID-19 crisis uncovered the shortcomings in women’s protection through exiting social security mechanisms and institutions. According to Abla Amawi, the Secretary-General of the Higher Population Council, violence against women in Jordan increased by 33% during the pandemic (Al-Mamlaka 2021a). In December 2020, the Minister of Political and Parliamentary Affairs, Mousa Al-Mayata, acknowledged the increased level of violence against women in Jordan, promising that Jordan is taking the necessary and practical steps to address the issue (PETRA 2020). Despite the official recognition and promises to act, the data shows a perception among the population in Jordan that violence against women increased during the pandemic. In fact, 50% of Jordanians agreed that there was increased abuse and violence against women in their communities, while 32% said the level of abuse and violence against women in Jordan remained the same (al-Mamlaka 2021a). The social security mechanisms in Jordan do not focus on women as a vulnerable group and do not provide them with the necessary economic and social protection or mechanisms for protection from abuse and violence.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which started in 2019 and reached Jordan in early 2020, has caused tremendous strain on global and local economies and public health services and caused panic around the world, leaving millions of people without a source of income. At the beginning of the pandemic, Jordan was already witnessing a financial and economic crisis, which worsened the situation for millions, particularly vulnerable groups such as informal workers, women and the youth. However, due to the unpreparedness for such a crisis, primary school students were greatly affected, due to the lack of the technological infrastructure needed for remote learning, which may have a medium-term effect on these children when they return to school. In this report, we examine the vulnerabilities and gaps of the social protection system in Jordan, along with the Jordanian population’s perception thereof, as well as how the government, INGOs and other stakeholders can turn this crisis into an opportunity to gain experience on how to bridge existing gaps, so that no one is left behind. Although the government of Jordan put in place several measures to contain of the virus and to mitigate its economic and social impact, the pandemic shed light on the tremendous inequalities and the extent of the country’s unpreparedness to meet such a challenge. The unequal access to basic services between urban and rural areas was a reality long before the pandemic, as V-Dem data indicates. Likewise, access to opportunities has been unequal at various levels for a long time, which may have exacerbated other inequalities in Jordan. However, as Jordanians living in rural areas accounted for 16% of the total population in 2016, it is difficult to measure the perception of the quality of services accurately, as one or two members of each household may be living in rural areas (Figueroa, Mahmoud and Breisinger 2018). There is an urgent need for intervention programmes that tackle these gaps in order to dodge additional adverse consequences at the social and socio-economic level in the country. As such, we propose the following set of recommendations:

The government should make more efforts to reach the country's peripheries (rural areas) and to provide services with decent quality, mainly healthcare, education and support for youth livelihood activities. Responsive structures and mechanisms should be established to review and take measures to bridge the gaps, so no person and no geographical area is left behind.

We recommend that special attention be paid to female workers. Informal female workers should be included in the livelihood program, education programme and, more importantly, the social protection system. The measures taken by the government may limit the ability of women to return to work or even work from home (compared to men). Specific measures and programmes designed to support women are needed during and after the COVID-19 crisis.

As there is a need for accurate and up-to-date data, we recommend creating a unified database and digital platform that allow access to updated information on vulnerable groups by the concerned institutions that provide social protection benefits.

We recommend covering informal workers with a designated social security programme to enhance the opportunities available to them. This should include labour regulations that address the specific situation of informal workers. While a considerable number of informal workers are affected by the measures taken by the government, they benefit the least from the programmes initiated by the government. There is an urgent need for funds and programmes to assist informal workers in mitigating the economic effects of the pandemic, which should include refugee informal workers. There is also a need for programmes to include these workers in the labour market after the pandemic.

We recommend expanding programmes that incorporate technology in primary education and provide teachers and educators with the necessary tools to manage online and off-class education programmes. This would help teachers, students and families shoulder the burden of off-school teaching in the future to prepare for any possible crisis.

Given the severe and unexpected consequences of the COVID-19 crisis and its aftermath, international non-governmental organizations, in coordination with the Jordanian government, should work to remove the barriers of including informal workers into the formal social protection systems. These efforts should meet the needs of the different vulnerable groups, such as women and the youth. Such coordinated efforts can mitigate the negative impact of COVID-19 in the medium and long terms.

From a policy perspective, emergency responses rooted in social protection must be developed to avoid further deterioration of living conditions and the fall of more people into the trap of poverty. In that sense, INGOs and the government of Jordan should support the development of an emergency response plan integrated within the social protection system.AB. 2020. “Arab Barometer Wave V 2018-2019.” The Arab Barometer. https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/.

———. 2021a. “Arab Barometer Wave VI-Part 2 (Jordan).” The Arab Barometer.

———. 2021b. “Arab Barometer Wave VI-Part 3 (Jordan).” Jordan: The Arab Barometer. https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-analysis-tool/.

Al-Mamlaka. 2021a. “410 آلاف أسرة تلقت مبالغ نقدية من المشروع الطارئ للاستجابة لكورونا.” Al-Mamlaka News Paper. https://www.almamlakatv.com/news/65293-410-آلاف-أسرة-تلقت-مبالغ-نقدية-من-المشروع-الطارئ-للاستجابة-لكورونا.

———. 2021b. “Violence Against Women in Jordan Increased by 33% during Corona’s Lockdown.” Al-Mamlaka News Paper. https://www.almamlakatv.com/news/74972-العنف-ضد-النساء-في-الأردن-ارتفع-33-خلال-فترة-الحجر-بجائحة-كورونا.

———. 2021c. “توقع صرف الدفعة 5 من الدعم النقدي لأسر تضررت من كورونا بعد شهرين.” Al-Mamlaka News Paper. https://www.almamlakatv.com/news/72608-توقع-صرف-الدفعة-5-من-الدعم-النقدي-لأسر-تضررت-كورونا-بعد-شهرين.

AP. 2021. “As Lebanese Got Poorer, Politicians Stowed Wealth Abroad.” News. AP NEWS. October 6, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/business-middle-east-lebanon-najib-mikati-eur....

Bartholomew, Luke, and Paul Diggle. 2021. “The Lasting Impact of the Covid Crisis on Economic Potential.” VoxEU.Org (blog). September 21, 2021. https://voxeu.org/article/lasting-impact-covid-crisis-economic-potential.

Calp. 2021. “Adapting Humanitarian Cash Assistance in Times of Covid-19.” Amman: The Cash Learning Partnership. https://www.calpnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CaLP-Cash-Adaptat....

GoJ. 2020. “Jordan Emergency Cash Transfer Project.” Amman: Government of Jordan. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/950581604948526387/pdf/Envir....

———. 2021. “Jordan Emergency Cash Transfer COVID-19 Response Project.” Amman: Government of Jordan. https://mop.gov.jo/EBV4.0/Root_Storage/EN/EB_HomePage/Additional_Financi...(SEP)_FINAL.pdf.

HRW. 2020. “Jordan: State of Emergency Declared.” Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/20/jordan-state-emergency-declared.

IMF. 2020. “IMF Executive Board Approves US$1.3 Billion Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility for Jordan.” International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/25/pr20107-jordan-imf-execu....

IRC. 2020. “A Decade in Search of Work.” Amman: International Rescue Committee. https://eu.rescue.org/sites/default/files/2020-06/A Decade in Search of Work FINAL.pdf.

Jawad, Rana. 2020. “Social Protection and the Pandemic in the MENA Region.” Social Protection organization. https://socialprotection.org/discover/publications/social-protection-and....

JMOH. 2021. “COVID-19 Statistical Report -Jordan.” Jordan Ministry of Health. https://corona.moh.gov.jo/en.

JRP. 2020. “Jordan Response Plan for the Syrian Crisis, JRP, Relief web.” Reliefweb.

MOIP. 2019. “National Social Protection Strategy 2019-2025.” Amman: Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MOPIC). http://haqqi.info/en/haqqi/research/national-social-protection-strategy-....

NAF. 2021a. “National Aid Fund of Jordan.” Official Website. https://naf.gov.jo.

———. 2021b. “National Aid Fund Programmes.” National Aid Fund. http://naf.gov.jo/AR/List/برامج_الصندوق.

———. 2021c. “همة وطن يصرف 27 مليون دينار لحساب المعونة الوطنية.” National Aid Fund Website. /Ar/NewsDetails/همة_وطن_يصرف_27_مليون_دينار_لحساب_المعونة_الوطنية.

PETRA. 2020. “المعايطة: الأردن اتخذ إجراءات عديدة للتعامل مع العنف ضد النساء.” Jordan News Agency. https://petra.gov.jo/Include/InnerPage.jsp?ID=161441&lang=ar&name=news.

Razzaz, Sussan. 2017. “A Challenging Market Becomes More Challenging: Jordanian Workers, Migrant Workers and Refugees in the Jordanian Labour Market.” Amman: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/beirut/publications/WCMS_556931/lang--en/index.htm.

Researcher. 2021a. Social Protection System in JordanSkype.

———. 2021b. Social Protection Systems in Jordan 2Skype.

———. 2021c. Social Protection System in Jordan 3Mobile telephone.

SSC. 2021a. “Social Protection Corporation of Jordan.” Official Website. https://www.ssc.gov.jo.

———. 2021b. “تقرير استجابة المؤسسة لجائحة كورونا 2020.” Amman: Social Protection Corporation. https://www.ssc.gov.jo/arabic/المكتبة-الالكترونية/تقارير-ودراسات/التقارير-السنوية/.

UNDP. 2021. “2020 UN Country Annual Results Report-Jordan.” Amman: United Nations Development Programme.

UNHCR. 2019. “Jordan Fact Sheet.” Amman: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

UNICEF. 2021. “How to Maximise the Impact of Cash Transfers for Vulnerable Adolescents in Jordan.” Amman: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

V-dem. 2021. “V-Dem Dataset V11.1.” Varieties of Democracy Institute. https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data/v-dem-dataset-v111/.

WB. 2021. “COVID-19 G2P Cash-Transfer Payments.” Washington DC: World Bank Group. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/229771593464525513-0090022020/origi....

WFP. 2021. “WFP Jordan. Country Brief August 2021.” Amman: World Food Programme. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2021 08 Jordan Country Brief.1.pdf.

Winkler, Hernan, and Gonzalez Alvaro. 2019. “Job Diagnostic Jordan.” Washington DC: The World Bank. The World Bank.

[1] UNICEF 2019, “How to Maximise the Impact of Cash Transfers for Vulnerable Adolescents in Jordan.”

[2] Tamkeen means enablement and empowerment

[3] Takaful translated as "solidarity" or mutual guarantee. However, it is a system of reimbursement or paying in case of loss.

[4] NAF, “National Aid Fund of Jordan”; SSC, “Social Protection Corporation of Jordan.”

[5] ; SSC. 2021. “تقرير استجابة المؤسسة لجائحة كورونا 2020.” Amman: Social Protection Corporation. https://www.ssc.gov.jo/arabic/المكتبة-الالكترونية/تقارير-ودراسات/التقارير-السنوية/.

[6] Al-Mamlaka, “توقع صرف الدفعة 5 من الدعم النقدي لأسر تضررت من كورونا بعد شهرين.”

[7] AB 2020, “Arab Barometer Wave V 2018-2019.”

Abdalhadi Alijla is a social and political scientist and science advocate. He is the 2021 International Political Science Association Global South Award. He is the Co-Leader of Global Migration and Human Rights at Global Young Academy. He is a co-founder of Palestine Young Academy in 2020. He is an Associate Researcher and the Regional Manager of Varieties of Democracy Institute (Gothenburg University) for Gulf countries. He is a Post-doctoral fellow at the Orient Institute in Beirut (OIB). Since 2021, he is an associate fellow within SEPAD, sectarianism, proxies and de-sectorisation at Lancaster University. Since April 2018, He is an associate fellow at the Post-Conflict Research Center in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Abdalhadi has a PhD in political studies from the State University of Milan and an M.A. degree in Public Policy and Governance from Zeppelin University- Friedrichshafen, Germany. He has been granted several awards and scholarships, including DAAD (2009), RLC Junior Scientist (2010), UNIMI (2012), ICCROM (2010), Saud AL-Babtin(2002) among others.

In 2016, he was a fellow of the Royal Society of Art and Science, UK. He worked for many NGOs and INGOs in the Middle East and Europe such as Transparency International, GiZ, EU Maddad Fund for Syria Crisis, and UNV among others. He is a member of the scientific and consultative committee of Center for Arab Unity Studies in Beirut. His writings appear on OpenDemocracy, Mondoweiss, Huffpost, Qantara, Your Middle East, Jaddaliya and other media outlets. His main research interests are divided societies, Rebel Governance, Democracy, Social Capital, Middle East Studies, and Comparative Politics. Abdalhadi is the author of the “ Trust in Divided Societies” by Bloomsbury Academics and I.B.Tauris UK.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3593-480X

Twitter: https://twitter.com/alijla2021

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/hadiabdalhadi8/