On Mixed Identities, Racism, and Activism in Lebanon; A Discussion with Nisreen Kaj.

This article highlights the trajectory of Nisreen Kaj, and looks into the intersectionality of racism. It goes over her activism on racism issues on an individual level, through her “Mixed Feelings” project, and through organisations.

To cite this paper: Léa Yammine,"On Mixed Identities, Racism, and Activism in Lebanon; A Discussion with Nisreen Kaj.", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2017-10-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSR.002.006

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/mixed-identities-racism-and-activism-lebanon-discussion-nisreen-kaj

In a recent article published in the New Yorker, which was quite popular online, mixed marriages between citizens of two different countries are described as playing a part in developing compassion and understanding between people in the world: “The awareness and negotiation of small differences add up to a larger understanding about the complexities of the world.”[1] Amidst growing globalisation, mixed marriages are indeed increasingly common and appreciated for their transnational multiculturalism. In Lebanon, however, due to the exodus of its citizens and its attributed “cosmopolitanism,” such intermixing is not a new phenomenon. Instead of being met with greater empathy, however, the children of some of these marriages are met with racism and marginalisation.

Nisreen Kaj is the child of a Lebanese national and a Nigerian national. When she turned 19 years old, she moved to Lebanon to pursue her higher education in her father’s country, and learn more about Lebanon’s culture as she had been living in Nigeria up until then.

“In Nigeria, I was in a Lebanese school but all my friends were foreign because in the school, there was at times a lot of tension between Lebanese and foreign kids, for a lot of reasons, so I just ended up in the foreign crowd. I didn’t really bond with the Lebanese kids, but I always identified as Lebanese. So coming here, I still had the idea I was Lebanese, there wasn’t a doubt in my mind about that, just that the kids at my school was a matter of personalities not clicking and some incidents of racism, I didn’t think it was a greater systematic problem. When I came here, I realised what I experienced in Lagos was a bigger problem here.”[2]

“Racism is intersectional by definition.”

Upon moving to Lebanon, Kaj was faced with a lot of discrimination and with the idea that she did not “look Lebanese.” It started on the individual level with comments from people and students at university. During those first few years, , having to deal with these experiences alone, she even thought of leaving the country but her father encouraged her to stay and finish her studies. The racism she faced wasn’t all from individuals, she also had incidents with members of the police who, assuming she was foreign, constantly stopped her and checked her ID papers – forcing the habit of always carrying her Ikhraj ‘eyd with her – with some apologising to her after learning she was Lebanese. Nisreen experienced institutional racism, first-hand:

“You see it in different ways, take university for example: a professor once made fun of the way Africans speak in class [by making incomprehensible sounds] as the whole class laughed. I was the only black student there. When I pointed out that what he did wasn’t very nice, he kicked me out of class. Or during my first semester, when I was walking to class […] and on the way some guys started calling me names “ya habashiyye,” “sharmouta,” asking how much I cost, etc. This was quite upsetting as you can imagine […] so I wrote to my professor telling him I wouldn’t make it to class, and because of that he told the security guards at the university to take care of me if anything happened. I had fights with students because of racism, it turns you into a different person. The issue with an institution like a university, where a professor had to take the initiative, this shows that there is no system in place that you can refer to. It’s systemic, an institutional problem, because individual people can be nice or not nice, that’s not the issue; the issue is that you have systems that don’t help address racism.”

For Nisreen, racism is by definition a systemic, intersectional[3] issue; it is a result of a legal framework and of socio-cultural constructs. It is a complex process of racialisation that touches on being a black woman in Lebanon, which often means being assumed to engage in a profession that is gendered, perceived as unclean and lower-class work. She has faced criticism, even from close friends, about her physical features like her forehead shape, the darkness of her skin and her hair. Thus, these comments went beyond race and compounded the aspects she was criticised for.

Around 2008, Nisreen attended a talk by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) on Migrant Domestic Workers (MDW) and the kafala system – under which migrant domestic workers opearte – which proved to be eye-opening about the bigger picture of racism she had been experiencing, and explained how this racism was deeply inscribed in Lebanese society. It allowed her to put things into perspective when it came to her understanding of racism: an array of intersecting oppressions which include gender, race, class, and socio-economic status.

“There was something bigger for me to do than just think about my own interactions with Lebanon”

Shortly after that, Nisreen started volunteering with a group supporting the rights of domestic workers. This involvement introduced her to cultural initiatives about race, and activism about MDW. It led her to collaborate with many initiatives and organisations over the years, like Taste Culture, Anti Racism Movement (with whom she is still involved as part of the advisory board), Insan association, Human Righst Watch, etc.

Throughout this volunteerism, Nisreen met a lot of people who played an influential role in her trajectory, some of whom are still present in her life and provide support and advice. It allowed her to envision and eventually start planning one of her main activist projects, the “Mixed Feelings” project which explored racism in Lebanon through the experiences of Lebanese of African or Asian heritage.[4] The idea for the “Mixed Feelings” project came about after having a discussion with an African American friend who was giving an ethics workshop at the American University of Beirut at the time and was trying to explain to students how racism was exemplified in the kafala (sponsorship) system, and that it wasn’t merely an issue of class.

“She was trying to explain to them that racism is not this thing of the racism of the 1700s, it has all these [intersecting] issues. [Students tried to justify how the kafala system is for the own good of the workers and protects them, or said that the discrimination faced by migrant workers was classism and not racism.] She then told them ‘ok, I have a friend who’s black but she’s also Lebanese and she faces the same kind of racism, how do you explain that?’ And half of the class said that if her friend was Lebanese then she should not be facing that kind of discrimination, and the second half of the class said there’s no way you could be black and Lebanese. The second part was very interesting for me […] AUB students who seem very, let’s say ‘exposed’, didn’t understand that people mix, that you can be black and Arab, or black and Lebanese. So I told her: let’s do a photography project on Lebanese who are black.”

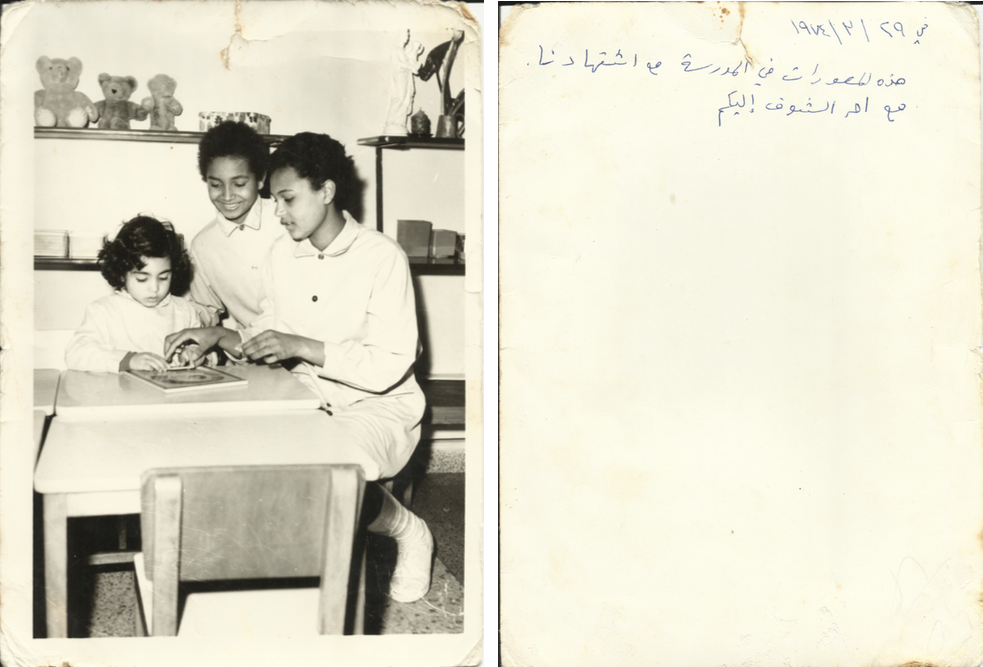

The project was put on hold after Nisreen’s friend left the country some time later, only to be initiated again when Nisreen met photographer Marta Bogdanska. Their collaboration materialised as the first phase of “Mixed Feelings” which consisted of an exhibition of over 30 photos of Lebanese of mixed origins, with their names, the villages they’re from, and quotes from interviews with them. The exhibition showed at various venues around the country with talks organised in parallel. The project challenged visual perceptions in order to show racism in the Lebanese context and from a Lebanese perspective. As Nisreen was personally involved in the project, she worked on it while applying to her MA in Racism Studies at the University of Leeds and carried on with her efforts abroad. Her research project was in fact based on the portraits and interview she already had, which permitted her to develop the project into a more academically-sturdy analysis. Consequently, the project became very dialogue-based, with talks organised with speakers from the field every time the exhibit was showing in a new venue. The overall objective was to raise awareness and create a discussion on the notions of mixed race in Lebanon.

“If Lebanese students don’t think black Lebanese exist, that’s very valid. I can berate them, get into fights but the truth is, maybe they don’t know, let’s say this is true. OK, so why not show them? The interactions I’ve had with strangers saying racist things to me on the street were never dialogue. You’re walking down the street, someone calls you a prostitute, you get angry, and fight back. There’s never any real conversation between the both of you, and understandably so, as you should not be put in a position to school someone discriminating you […] Well, I thought people like to talk, I want to have a conversation, and what better way to start that than through photos, which rely on that shock factor, so people are engaged visually and through a conversation.”

The project was collaborative and involved the participants who had their portraits taken and exhibited: they participated in some activities relevant to planning, and gave interviews to media outlets about the project. Nisreen gave participants ownership of the project and accordingly, many became invested in it, volunteering on the ground, and attending talks to address questions and talk to attendees.

In its first phase, “Mixed Feelings” toured 6 locations from the south (Sour) – as earlier waves of migration to West Africa originated from south Lebanon –to the north (Tripoli) of Lebanon, in collaboration with universities as well as municipalities.

“Tripoli was my favourite part of the project. We went to the al-Manar university in Abu Samra. […] The head of department apparently made attendance mandatory for undergrad students, so the room was completely full and we had an actual debate. Like it was arguing, disagreeing, and it was perfect because people were not afraid to verbalise how they felt. Like there were even African-Lebanese people that said ‘when we go to Africa, we face discrimination too’ and I would ask them what and then explain that this was still within a system that advantages them and when they face discrimination, it was discrimination yes, but it deferred from racism as ‘it’s based usually on thinking you have money or access to things they don’t. Whereas in Lebanon, there’s a process of racialization based on inferiorisation, where people are seen as sub-human, where a sponsorship system is in place likened to modern slavery, and so on.’ I was trying to explain to them the nuances, [and the history of Lebanese as part of the colonial presence, of the administration, in parts of Africa.] The kids there were also not malicious or angry, they wanted to keep talking and explaining their point of view even after the talk. They were friendly and remembered me when I came back a week later to dismantle the exhibit.”

In its second phase, the exhibition evolved to include family pictures. The team met 17 families and heard stories from the perspectives of the rest of the families, specifically the foreign mothers, which highlighted its own set of human experiences of racism in Lebanon. Likewise, the second phase aimed to underscore the various dynamics at play when a family is mixed. For Nisreen, family is a core unit of institutions in Lebanon, from religion to politics, which made it the obvious next step for the project, as it demonstrates how sameness and otherness are negotiated within the family unit, and how this affects different family members.

“These families shared amazing experiences, really insightful stories, everyone was super easy-going and laughing about their experiences. Of course that’s because these are people whose marriages survived racism, I’m sure there are people who didn’t have happy endings to their marriages, but the people we found were still married, still happy and positive, and the women especially were really full of spirit. You start feeling stupid about your experiences, like ‘whoa these women are so strong, I have a passport to show and shut people up, they don’t.’ When they first enter that new family, it’s them against that family. Everyone likes the kids even if they’re mixed, brown, whatever, because they’re their son’s kids, but these mothers have to deal with a lot from the family side, and some of the stories we heard were really shocking.”

Through personal archives of family photos – a very familiar and relatable medium – this second part of the “Mixed Feeling” project brought the importance of solidarity within a family, and the role men play in making their families accept the women they choose as partners, to the forefront. Nisreen pointed out here that these stories were enjoyable to discover on the human level, and not just in the scope of research.

“Everyone is actively involved on these issues in a way, why should I call myself an activist?”

Deeming racism a very sensitive topic to discuss, Nisreen understands how most civil society actors address the issue of racism through other lenses and under different “umbrella” themes, such as migrant domestic workers and the kafala system, part of a larger focus on labour. However, she finds it essential to focus on legal issues, tailored towards action, advocating and lobbying for actual law reforms, as racism is an issue on the systemic level. Additionally, she considers there is a need for sensitivity training on an institutional level, in schools, workplaces, and for members of the LAF and ISF, in addition to the monitoring and proper implementation of such trainings. Most importantly, she points out the need to include and involve migrants and black people in these actions.

“A lot of times when we do activism, we don’t involve the concerned parties. This is not just specific to Lebanon. There is a tendency to talk about ostracised and marginalised groups without involving them. They’re rarely on advisory boards, expressing what they want, leading marches. I understand why that happens, their situation is often illegal, but it is also not unrealistic to have that kind of approach. So I think NGOs are more and more aware of this and are involving migrant domestic workers in their actions.”

Nisreen brings up the needs for sustainable and independent modes of operations, as well as the need for more collaboration. Indeed, echoing the findings from Lebanon Support’s report on gender interventions,[5] she also mentions duplication of work, possessiveness over funds, and the shifting of programmes according to funding as creating hindrances and setbacks for work addressing discrimination.

“It’s an unfortunate reality we have to deal with. It’s about survival, they need funds to survive and so, programmes change and shift. But so my question would be how can third sector organisations be sustainable so they don’t just rely on funding or volunteer work, which isn’t always reliable?”

While she personally finds marches to sometimes be alienating and intimidating as a woman of colour, activism is, for Nisreen, ongoing: like the women and people from the “Mixed Feelings” project who always try to educate those around them. Still, she is reluctant to identify as an activist since she is not always working in the field and proactive, and doesn’t want to undermine the daily activism of other less visible people. She also points out that some self-identified activists are privileged, and even detached from the issues they advocate for.

“I feel like a lot of activists are not always nuanced on these issues, understandably because it doesn’t affect them directly. I’ve had disagreements on how to tackle these issues with people who would do an activity on racism, and if I criticise it a bit, as a person who’s black and who studied the subject, my comment would be readily dismissed because ‘I don’t know Lebanon very well.’ I have to remind people that I am Lebanese and have lived here 16 years, and that I can tell them what offends me given that I actually live this.”

Above all else, Nisreen values creating dialogue as the way forward – whether with individuals, or on a programming level where she sees it essential to involve the private sector, education sector, or municipalities, rather than restricting activities and interventions to the non-profit and third sector. In that vein, she would like to carry on working on cultural exchanges in the future, specifically highlighting the cultural interactions between Lebanon and the continent of Africa, notably West Africa.

* This paper was first published in the 2nd issue of the Civil Society Review.

[1] Lauren Collins, “Foreign Spouse, Happy Life,” The New York Times, 15 October 2016, available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/16/opinion/sunday/foreign-spouse-happy-li... [last accessed 22 October 2016]

[2] This article is based on an interview by the author with Nisreen Kaj, Beirut, July 2016.

[3] For a definition of “intersectionality,” refer to: Lebanon Support, Gender Dictionary: Traveling Concepts and Local Usages in Lebanon, Beirut, Lebanon Support, 2016, available at: https://civilsociety-centre.org/resource/gender-dictionary-traveling-concepts-and-local-usages-lebanon-%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B3-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D9%85%D9%81%D8%A7%D9%87%D9%8A%D9%85-%D9%85%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%82%D9%91%D9%84%D8%A9

[4] For more info on the project, refer to Nisreen Kaj’s website: http://www.thisisnisreen.com

[5] Lebanon Support, “Overview of Gender Actors & Interventions in Lebanon. Between Emancipation and Implementation,” Civil Society Knowledge Centre, 2016, available at: https://civilsociety-centre.org/resource/overview-gender-actors-interventions-lebanon-%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AD%D8%A9-%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A9-%D8%B9%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%81-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%86%D8%AF%D8%B1 [last accessed 10 October 2016].

Léa Yammine is a creative and researcher. Her main research areas and work revolve around on communication, visualisations, social justice, civil society, and gender. She is currently the co-director of the CeSSRA.

Léa holds a BA in Graphic Design from the American University of Beirut, and an MA in Culture, Creativity & Entrepreneurship from the University of Leeds, UK.

Email: lea@socialsciences-centre.org

Twitter: https://twitter.com/lea_yam