Between Fitna, Fawda, and Feminism: Implications of Religious Institutions on Lebanon’s Women’s Movement

In Lebanon’s recent years of post-war development, the women’s movement took strides to further the status of women. Such strides have included campaigns to reform women’s personal status laws towards citizenship, nationality, and most contentiously for protection against gender-based violence. Since the end of the civil war and at the zenith of the women’s movement, women’s advocacy groups were seemingly gaining momentum towards attaining reform, until the Lebanese State reached disintegration into its current political deadlock. Where Lebanon has become politically enmeshed within the protracted conflict in the region, among civic society, the women’s movement has endured the brunt of reactionary politics. This paper means to problematize the Sectarian regime in Lebanon as an agent of social control and a body politic of reactive policies towards women in Lebanon, wherein the women’s movement has only received empty concessions that could exacerbate already bleak conditions.

To cite this paper: Sandy S. el-Hage,"Between Fitna, Fawda, and Feminism: Implications of Religious Institutions on Lebanon’s Women’s Movement", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2015-02-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.001.30003

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/between-fitna-fawda-and-feminism-implications-religious-institutions-lebanon’s-women’s

Introduction

Religious institutions in Lebanon take on a role beyond social control and introduce a political structure in how people are governed, but more comprehensively in how Lebanese relate and find representation within their social communities. A transient student residing in Mar Mikhael, Beirut, will relate and find representation within the sociopolitical arena in vastly differential manners than a retired mechanic residing in Mount Lebanon – or, in Tripoli, nearest the borders of war-torn Syria – where social strife or cohesion is achieved through factors unique to its sociopolitical climate. In these examples lies the character of a pluralistic society against the backdrop of an autonomous religious institution concisely referred to as a sectarian political system.

As a resolution in the Ta’if Accords to demobilize warring parties, sectarianism was further established as a system for Lebanese political representation. Just like the recent attempt to implement a quota system for women in municipal elections,1 for the religious polity, sectarianism created equal representation in political bodies with decision- making power. In modern-day Lebanon, and still existing within this political structure, marginalization and oppression has continued, alongside the international wave of neo-liberalism and effects of globalization.

This paper means to address a long-standing relationship between religion, politics, and women’s rights in Lebanon. Where the political structure of sectarianism is a well-documented hindrance to development, women have endured a particular brunt from institutionalized religion.

Role of religion in Lebanon

In accordance with the wide usage of the Old Testament, religion has been a source of social knowledge since the inception of humankind. Taken from the biblical tale, commonly referred to as “Original Sin”, Eve transformed herself from an eternal guard to the tree of life into a transient human being by a single act that would forever characterize disobedience as the ultimate sinful act. As a historical anecdote revisited, Eve’s story provides a pearl of wisdom. Regardless of the decision taken to consume the sinful fruit, Eve’s action was informed by faith. In one respect, Eve was informed by the entity known as God of the ensuing repercussions for disobedience. Concurrently, Eve was further swayed by the persuasion of the literary and antagonistic perspective of God’s nemesis, the serpent, and an embodiment of Satan. The literary tale, as it follows, presents the framework that social knowledge in a facet is informed by religion. Whereas, Eve enacted a decision informed by faith.

Evidenced by religious credence to Eve’s story, this example depicts how social knowledge may be informed by religion,23 wherein religion further provides a means for community members to share similarities and build a communal trust. But also, and more relevant to this paper, religion is studied as a factor that informs the body politic and identifies communities by their constituent inclinations. In theory, a person residing in a more cosmopolitan environment will benefit from the variety of discourse in politics and diversity among representatives. In application, the notion of a cosmopolitan community in Beirut does not so much lend to politically diverse discourse, but rather the features of a culturally and religiously diverse community give rise to an equally diverse civil society. Wherein, the state, as a body politic, serves only as the mediator between different social and sectarian communities. The preceding description is an attempt to illustrate the sociopolitical function of sectarianism, altogether while defeating pre-modern notions.4

In its history of nation-building, religion served as the foundation of Lebanese identities.5But only in recent decades did politics enter the discourse along with state-building, and religion consequently became politicized within the structures of sectarianism.6Lebanese identities were effectively altered by the significance of religious identities crossed with political affiliations. During the civil war of 1975, these divides further entrenched religion as a political vehicle. These patterns of emerging and/or existing sectarianism are presently manifested in the body politic. Political parties often include members of society who are reintegrated members of the civil war.7 One scholar illustrates the trend dating back to historical Lebanon when:

“[…] it was a culture of the elites, who fought to keep their privileges intact and to maintain a hierarchical social order; on the other hand, sectarianism also reflected popular visions of the future, of liberation in a new landscape… the war of 1860, was in fact the great failure of a single sectarian identity to impose itself in a world in transition.”8

Makdisi’s recount of political history in Lebanon ultimately purports, ‘Sectarianism is an expression of modernity’9 This notion is a premiere feature of the driver of institutionalized religion within Lebanon’s political system. The modern state, formally recognized as the Republic of Lebanon, experienced a second coming with the adoption of the National Reconciliation Accords, popularly referred to as the Ta’if Agreement of 1989. Prior to the accord that meant to restore political ‘stability’ among warring political factions, the National Pact of 1943 had initially institutionalized a confessional state.1011

Between the National Pact of 1943 and the National Reconciliation Accords of 1989, religion was enshrined by nation-state ideals to develop a “new and more equitable confessional system.”12 Religion has, thus, been both a driver and solvent of civil strife.

In sociopolitical terms, institutionalized religion occurs at the union of church and state, or said differently, a contemporary manifestation of organized religion in modern societies exists as institutionalized religion.13 To elucidate on the sociopolitical function of sectarianism, the concept of civil religion gives meaning to its political determination as a governing agent. Modern thinkers on religious society such as De Tocqueville, Rousseau, and Durkheim established civil religion as a stabilizing function for governance.14 In Lebanon, the application of this principle sees religious identities serving as a means for representation of citizenry. Wherein the next section of this paper will point to the Constitutional form of sectarianism, this section will discuss sectarianism in its political form of governance. To return to the original point brought by Contemporary remarks, the differentiation between civil religion as a stabilizer and civil religion in Lebanon, in its modern form, sectarianism perpetuates an archaic power structure of decision makers who date back to the civil war era. The civil war in character saw such mobilization by warring factions along those religious identities. Thus, civil religion is thereto a function of governance. However, and as presented in this paper, and counter to Contemporary thinkers, civil religion is problematized as questionable in modern Lebanese politics, and despite the notion sectarianism meant to serve as a stabilizing political structure in the Ta’if Agreements of 1989.

Robert Bellah recounted de Tocqueville, Rousseau, and Durkheim in American politics when civil religion was boisterous and religion had a ‘divine transcendence’ across the nation.15 During this period, American politics was driven by civil religion insofar as policymaking carried an undertone of religious superiority in American Christianity. Ever since, present-day civil religion in America has immensely declined from the daily lives of people due to the rise of individualistic and consumer-oriented value systems. This is largely a contrast to sectarianism in Lebanon where a civil religion and ‘divine transcendence’ was the reconciling factor to the civil war. Thus, Bellah’s notion of the divine transcendence in politics, where the crux of religion and governance intersect, is an identifying marker of civil religion and a facet of sectarianism in the modern existence of church and state.

Religious institutionalization (per Article 20 of the Constitution)

The discrepancy between attaining equality and a non-existence of civil rights serves as the underlying grievance in Lebanon’s women’s movement. This hurdle presented by the Constitution is apparent in the most recently enacted law to protect families from domestic violence. Parliament gutted the law, from a gendered bill to protect women from domestic violence (or known as Violence Against Women, VAW) to a law that now protects family members generally from domestic violence. The schism between attaining women’s rights and non-existence of civil liberties is further exacerbated by a vociferous campaign from religious courts that doggedly rule against a law to protect women from domestic violence. Moral and religious reasoning maintains that gendered laws could disintegrate the fabric of family ties. Further, where women have died at the hands of a family member(s), civil court decisions ruled that domestic violence was not the proximate cause of death.

The Lebanese Constitution provides under Article VII equal rights for all people “before the law.” This canon is important to activists who are working to address gender inequality and gender motivated or gender based violence when it comes to shaping laws. Under Article VII, this portion of the Constitution purports that laws created by the government shall be equal across all Lebanese citizens. This article however is not interpreted to state that equality is an inherent right and that all Lebanese are equal absent a legislative requirement. Rather, the Constitution mandates to parliament that laws shall reflect civil liberties and equality only where legal codes mean to mandate civil liberties and equality. The language under Article VII renders equality as conditional, provided the existence of a legal framework. Thus, only where laws either mandate or express a legal right, Article VII may be asserted.

From a bottom-up approach, for activists, the newly created legal framework around domestic violence will require the amendment of the law or passing new laws for gendered rights. Whereas, in contrast, researchers have called for an internationalist framework, a top-down approach through a UN convention.16 This approach would in application hold governing bodies in Lebanon accountable for enacting said commitments to monitor and address violence against women (VAW).

According to some case studies, scholars have noticed for a bottom-up approach, inclusionary politics is attained through means of weaving principles of civil ethics, such as gender equity, into local discourse.1718 This strategy must be interdisciplinary, and is often done through a process of working from within the system or through revolutionary change. These two polarized strategies utilize the resources of either an existing instrument or an instrument in development. For the former, to meet interdisciplinary means, activists must look for instruments and existing frameworks from institutions that emphasize customary practices. The difficulty in asserting Amendment VII, however, will counter legal restrictions as provided by Article 20, where “The law shall determine the conditions and limits of the judicial guarantees.”19 Thus, the constitutional framework provides deference to rulings in religious courts and jurisprudence according to existing legal structures.

Factors that constitute local discourse stem from three elements posited by both Abusharaf and Anthropologist Suad Joseph: local culture, the “spatio-temporal” context in social relationships, and the legal treatment of citizenship rights.20 With respect to pluralistic societies, Joseph proposed a triangular relationship with cultural sensitivity to Lebanon’s case. Whereas, triangulation of state, civil society, and kinship, or private domain, fosters “people’s commitments [to remain] grounded in kin and community, and they carry these commitments with them, whether in the civil or state spheres.”21

In Lebanon, federal and national institutions have proven to be obstructive to the goals of gender equity as a result of patriarchal structures, where decision-making is expressed under Article 20 to provide a clear delineation that “judicial power shall be exercised by courts of various degrees and jurisdictions.”22 Whereby “the law shall determine the conditions and limits of the judicial guarantees,” the Lebanese Constitution is constrained or defined through constitutional interpretation from existing laws. Although this stipulation is inherent to the ideology of a democratic republic, sectarian divisions continue to mar Lebanon’s treatment of constitutional interpretation. Perhaps inadvertently, the Doha Agreement of 2008 serves as a prime example where modern interpretation of Article 20 further provides deference to sectarian structures. Under the 2008 agreement, Lebanon and its allies drew a resolution over sectarian strife to elect a president and form a future “national unity government.”2324 The accord, in essence, garnered a concession to sectarianism by allocating veto-power and further representation to the ‘opposition’ party and the parliamentary majority.25 While the agreement meant to bring forth order for parliament to reach a consensus, move along from strife, and commit to form a national government, the agreement, in isolation, strengthens sectarian structures, and reinstates the tenet of ‘church and state’.

Implications of Religious institutions

The manifestation of institutionalized religion bears effect on daily Lebanese life through various facets that ultimately determine the political and social governance of people. As a unifying structure of governance, the union of church and state carries with it implications on the freedoms of citizens. In this paper, the argument has sustained an analytical account of the sectarian political structure.

Herein, the paper will discuss the effects of sectarianism on women’s citizenship towards the Lebanese state. Joseph articulated this intersection across civil rights and state dominance to “further reinforce communalist views of citizenship that tend to diminish women’s roles and rights as citizens.”26 The plight of women in Lebanon by offense on women’s liberties is a resultant factor of the patriarchal, sectarian political structure. Pointedly, the complexities that arise from ‘church and state’ take effect in pervasive manners towards women especially, and unevenly across sects. The state as a result creates and reinforces agents of social control and a socio-political imbalance resembling de-facto gender segregation.

-

Agents of social control

It is indisputable that Lebanon’s women’s movement has languished at the hands of an unresponsive government. The distinguishing feature between the recent past and the contemporary temporality of the women’s movement lies in the structure of organizing and mobilizing members of women’s advocacy groups. In Lebanon, inherent characteristics of structure, relations between other groups and organizations, power dynamics with ruling elite, and funding are enduring determinants of an advocacy group or organization’s operability.27 Lebanon’s women’s movement widely consists of professional women’s organizations that “do not fit the…developmental paradigm [and] rather [sic] are corporatist and elitist structures that fail to address and meet ordinary women’s needs.”28

The Lebanese state appointed a group of women to the National Commission for Lebanese Women (NCLW), an “official,” national organization to oversee the progress of women‘s status in post-war development.29 Since 1995, the committee has been primarily responsible for overseeing drafts of national strategies for achieving women’s advancement and gender equality under the U.N. conventions of CEDAW (Convention to Eliminate Discrimination Against Women). In parallel, the NCLW distributes assignments to women’s NGOs in civil society to bring social and political awareness to internalized contentions. Through a policy of top-down funding and agenda setting, the NCLW is simultaneously responsible for allotting U.N. funding and for institutionalizing partnerships between civil society groups and international agencies.

The socio-political harm in allocating the vast majority of leverage to the NCLW reflects in its bias to support women’s groups that will similarly adopt the same characteristics, mechanisms, and processes. Since its official establishment in 1998,30 the NCLW has been in charge of campaigns for women’s rights. However, its formal structure does not grant decision-making power, and thus functions alongside the sectarian, patriarchal state. The NCLW’s role has granted women opportunities to participate in international partnerships to build an institution for women. However, without the formal allocation of decision-making nor bargaining power, the NCLW is at risk to become an idle organization, with a greater risk at failing to achieve goals delineated in such conventions as CEDAW.

Researchers have also characterized women advocacy groups within the statist apparatus as “corporatist, elitist and sectarian-based structures [that] permeate and dominate the women’s associational landscape.”31 Further, and most evocative of a patriarchal system, the NCLW has been largely a professional network for qualified, educated women. Implicit in the organizational structure of the NCLW is an overwhelming gender disparity of women in actual realms of leadership and political decision-making, relegating them instead to working in the sphere of civil society.

As for its bias for working cooperatively with the patriarchal system, the NCLW shares this mechanism with its domestic partners, by forming cooperative, complacent, and almost conformist attitudes to the hierarchal market structure of neoliberalism and globalization that ultimately prioritizes funding and partnerships with prestigious affiliations over grassroots organizing. Within this reasoning, Khattab wrote on the permeation of a hierarchical structure on the women’s movement at large, where funders as “international aid agencies strengthen [the] corporatist rather than grassroots associations, contribute to marginalize women’s interests and needs, and impede comprehensive reforms.”32

For the women’s movement, this is hypocrisy on behalf of the NCLW. Rather, the NCLW is a product of segregated political participation between men and women, and its implicit cooperation with the state only enables the patriarchal character of decision makers. The segregation of women from decision-making positions is noticed in the gendered structure of the NCLW, where its position in politics is largely to displace international pressure on women’s rights from the hands of the elite. In this dynamic, the NCLW and its community of women’s advocacy groups inevitably become the scapegoat for the state’s lack of responsiveness, while the cycle of fragmentation between women’s advocacy groups continues. Although since the inception of NCLW, an international political opportunity structure has enabled the growth of women’s advocacy NGOs in Lebanon; this growth is but a number that represents an exponential admittance of activists into civil society. A lack of output on behalf of legislating women’s rights policies continues to be a source of contention. Presently, the NCLW’s role continues to serve as a constrictive umbrella organization for mobilizing associational organizations in Lebanon’s women’s movement.33

This section argues that CEDAW under Security Council Resolution 132534 has provided the “ideological package” for the grassroots women’s advocacy groups to organize and implement reform. The convention’s connectedness to supranational influence, and its domestic appeal for women’s liberation from discriminatory offenses simultaneously instigates an opportunity structure for contentious politics between women’s aspirations for women’s rights and the patriarchal system’s lack of consensus. Yet, where CEDAW provides the framework, or ideological package for signatory member-states to identify women’s issues, contention persists. Bluntly, the State refuses to acknowledge a gender component required to administer laws towards gender equity.

CEDAW is a UN drafted convention, which has stood for the women’s movement as both a tool for framing grievances and for framing transformation of Lebanon’s future for women’s rights. However, the technique of translating framing from bridging support for women’s rights and employing the assistance received in response (externalized contention) followed by transformation is precisely where Lebanon’s women’s movement has broken down in the face of state hegemony.

In Lebanon, externalized contention is directed at both contentions with the state’s reservations on articles 9 and 16, its total refusal to ratify legislations, and towards the committee of CEDAW. Contention against the latter body largely regards the committee’s lackluster efforts to provide a framework of CEDAW exemplary and applicable to Lebanon’s culture, society, and political system. This contention has come forth as an admission from objections and condemnation of Western countries against Lebanon’s “incompatible and inadmissible” claims for CEDAW.

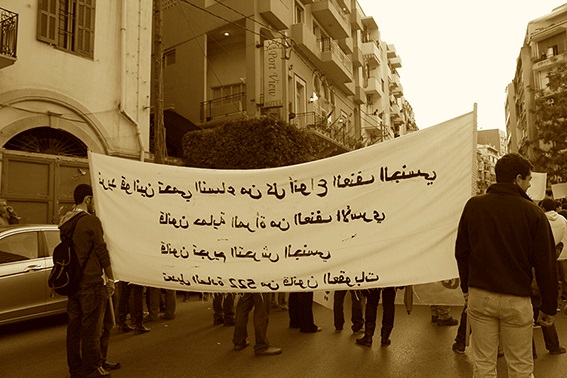

The mechanism of “frame bridging” brought forth a grassroots movement in support of CEDAW by Lebanon’s women’s advocacy groups. Women’s advocacy groups formed campaigns, at times in congruence, to promote positions in support of CEDAW principles where the State denies such rights. Frame bridging, according to social movement theorist Sydney Tarrow35, occurs when opponents rally towards an inter-sectional cause. In building the women’s movement in Lebanon around a civil society of women’s advocacy groups, campaigns to remove reservations from CEDAW rallied activists, scholars, and organizations around its specific issues. Frame bridging began at the inclusion of bottom-up organizing. Such grassroots campaigns and protests focused on KAFA’s draft law (The Law to Protect Women from Violence) to eliminate gender-based violence and protect women, CRTD-A’s campaign for Nationality laws, LLWR’s variation on CRTD-A’s campaign with an additional emphasis on article 9 of CEDAW, and the UNDP-CFUWI coalition, with additional support from LWDG, LWC, LECORVAW.36

From the perspective of state-level analysis, Khattab attributes the fragmentation seen in grassroots organizing as a failure to launch a Gramscian ‘war of position’ against the sectarian regime. However, from the perspective of internationalism, the disunity of grassroots organizing has failed to produce campaigns that engaged the target public through campaigns with Gramscian ‘common sense’. According to scholars of transnational activism, for a transnational campaign to successfully translate global framing into local framing, movement organizers must be both consumers of resources and producers of new ones relevant to the target demographic:

“Proposing frames that are new and challenging but still resonate with existing cultural understandings is a delicate balancing act, especially since society’s ‘common sense’ buttresses the position of elites and defends inherited inequalities. It is particularly problematic where activists attempt to import symbols and forms of action from abroad.”37

Organizational and associational leaders of women’s advocacy groups are not inherently hostile to each other. However, the difficulty of unpacking an imported framework such as CEDAW into a mostly traditional and patriarchal society is a daunting task, which requires cooperation among individuals and groups in the women’s movement. Yet, consensus amongst women’s advocacy groups is but one facet of the success of translating the global framework of CEDAW for women’s rights into a local frame. Aside from consensus across grassroots organizers and women’s advocacy groups, for both CEDAW implementation and a national social movement in favor of women’s rights, movement organizers and activists will have to promote common sense framing to the wider society of Lebanese. This task is further exacerbated by the opinion of ruling elites, who attest to an infringement of CEDAW’s ‘Western’ dimensions, and demand reservations on articles 9,3816,39and 29,40 (which dictate nationality, women and family,and authorization to supranational arbitration on state party disagreements over CEDAW interpretation).41

2. De Facto Gender Segregation

The previous section argues a two-fold effect of religious institutions on women’s status in Lebanon. Since the inclusion of Lebanon in international efforts to improve women’s rights, the women’s movement has experienced a backlash of this inclusion to the extent existing political structures are not compatible with the needs of local actors. Reform for the status of women in Lebanon may begin at the juncture of the following areas: through addressing women’s level of political representation; gender-based violence; and a women’s quota system for parliamentary elections. Most recently, the Lebanese state did enact a policy of inclusion for women into the security-state apparatus by enlisting in the state’s law enforcing body.

Towards political inclusion, the debate around gender quotas is relevant, lively, and progressive. Scholars on the topic in Lebanon agree there are complexities to consider such as the effectiveness and political change that could result of women’s inclusion.42

However, it is undeniable due to Lebanon’s recent political deadlock, and since last national elections occurred in 2009, the country has shown dismal advancement for women’s political participation. A recount of electoral campaigns in 2009 witnessed “of the more than five-hundred candidates running for a seat here in the Lebanese parliament, only twelve of them [were] women and judging from previous election results, it [was] unexpected that even half of them will [sic] make it.”43 A post mortem of the 2009 parliamentary elections reflected staggering low results with only four women elected from a bracket of 128 to be Members of Lebanon’s 2009-2013 parliament.

Secondly, addressing gender-based violence in Lebanon, it’s prevalence, and unfortunate existence requires that policy makers recognize how gender is utilized to divide Lebanese society. Where enough women are murdered on a monthly basis by their spouses or amale relative, there is enough evidence brought forth by activists and legal professionals to justify a gendered intention in cases of criminal and social harm.44 In 2012, and after staunch insistence by the women’s movement, clergy members recognized the social harm insofar media campaigns displayed remarks condoning violence against women (VAW).4546 However, and despite the flagrant denouncement against VAW, clergy members again offered but a shell of reform.

Further, and interestingly, the state’s admission of nearly 600 Lebanese women into police enforcement is yet another concession to the status of women in Lebanon. Since 2012, women have been admitted into the state security apparatus as law enforcers. Roaming with authority and along the Beirut streets, for the first time in post-war Lebanonwomen formed a portion of the Lebanese Internal Security Force, however, not within the formal military and combat sector. Commander of the patrol forces, Robert Jabbour, stated of the inclusion:

“[Women] will be assigned to police work, such as inspections and investigations. They will be deployed as patrol officers in prisons, in police stations, and in many other cases where women’s presence is of more added value than a man’s. These women will cause a major shift in the ISF’s work and capabilities; they will be able to fill many gaps, especially relating to children’s issues and domestic violence.”47

From this image, the role of women is still largely ceremonial, and second-rate to their male colleagues. Such inclusion within the police unit further depicts the furtherance of women’s responsibility to uphold societal mores, rather than delegated decision-making positions within central bodies of governance.

Conclusion

The preceding sections of this paper attempted to provide a linear progression through three components of the main argument of whether reform towards women’s rights and gender equality could in parallel to religious institutionalization. Where religious institutions have offered empty concessions to the women’s movement, top-down organizations such as the NCLW, too, are not conducive to challenging the patriarchal political system, whether at a state or international level. As a result, intellectual cleavages to the debate of women’s inclusions in Lebanese politics still point to whether the existing democracy deficit in the country is a result of obstruction to women’s status, and from there a lack thereof political participation, and whether involvement of women could facilitate more democratization through policy reform.48

Bibliography

Hussein Abdallah, “Lebanese rivals set to elect president after historical accord,” The Daily Star, English, 22 May 2008.

Adila Abusharaf, “Women in Islamic Communities: The Quest for Gender Justice Research,” Human Rights Quarterly, 28(3), 2006.

Robert Bellah, “Civil Religion in America,” Daedalus, 96(1), 1967.

Elinor Bray-Collins, “Muted voices: Women's rights, NGOs, and the gendered politics of the elite in post-war Lebanon”(Doctoral dissertation), 2003.

James Christenson & Ronald Wimberley, “Civil Religion and Religious Identities,” Sociological Analysis, 42(2), 1981.

John A. Coleman, “Civil Religion,” Sociological Analysis, 31(2), 1970.

Allan Eister, “Religious Institutions in Complex Societies: Difficulties in the Theoretic Specifications of Functions,” American Sociological Review, 22(4), 1957.

Shireen Hassim, “Terms of Engagement: South African Challenges,” African Gender Institute, University of Cape Town, Feminist Africa, Issue 4, 2005.

Suad Joseph, “Gender & Citizenship in Middle East States,” Middle East Report, 198,1996.

Suad Joseph & Joseph Stork, “Gender and Civil Society: An Interview with Suad Joseph,” Middle East Report, 183, 1993.

Ariel Keysar & Barry A. Kosmin, Secularism, Women and the State: The Mediterranean World in the 21st Century, Hartford, Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture, 2009.

Lara Khattab, Civil society in a Sectarian Context: The Women’s Movement in a Post-War Lebanon, Beirut, Lebanese American University, 2010.

Hassan Krayem, The Lebanese Civil War and the Taif Agreement, Beirut, American University of Beirut, 23 May 2003.

Constitution of the Republic of Lebanon and Its Amendments, 1925, 1995 [English].

Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, Ltd., 2000.

Elizabeth Picard, “The Demobilization of the Lebanese Militias,” Oxford, Centre for Lebanese Studies, 1999.

Daniela Rosche, “Close the Gap: How to Eliminate Violence Against Women Beyond 2015,” Oxfam GB, 11 March 2014.

Riwa Salameh, “Gender Politics in Lebanon and the Limits of Legal Reformism,” Civil Society Knowledge Center, Lebanon Support, 16 September 2014.

Security Council Report, Letter dated 22 May 2008 from the Permanent Observer of the League of Arab States to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council, English, 2008.

Sidney Tarrow, The New Transnational Activism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

UN Publications, Declarations, Reservations, and Objections to CEDAW, New York, United Nations.

- 1. Dalila Mahdawi, “Baroud to champion 30 percent women’s quota in politics”, The Daily Star, English, January 16, 2010, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2010/Jan-16/55908-baroud-to-champion-30-percent-womens-quota-in-politics.ashx#axzz3JZHho7ia [last accessed January 1, 2015].

- 2. Following the debates on the role of religion in society, John Coleman presents Emile Durkheim’s assertion that religion “integrates” society (John A. Coleman, “Civil Religion,” Sociological Analysis, 31(2), 1970, pp. 67-77). Regardless of whether Durkheim’s assertions hold truth, the logical underpinning follows that religion is a producer of shared, social knowledge.

- 3. Allan Eister operationalized religion to serve as both a cohesive function and a rivalrous function to creating social norms and to challenging “prevailing” norms, where in essence religion, whether as a cohesive function or a divisive function, embeds social knowledge (Allan Eister, “Religious Institutions in Complex Societies: Difficulties in the Theoretic Specifications of Functions,” American Sociological Review, 22(4), 1957, pp. 387-391).

- 4. Ussama Makdisi, in a recount of sectarianism in Lebanon, rejects pre-modern notions that sectarianism is an archaic, even barbaric function, and rather asserts the goals for sectarian politics is a modern solution to internal strife and communal ills. Makdisi, 2000, see note below.

- 5. Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, Ltd., 2000.

- 6. Ibid, p. 167.

- 7. Elizabeth Picard, “The Demobilization of the Lebanese Militias,” Oxford, Centre for Lebanese Studies, 1999.

- 8. Makdisi, op. cit., p. 167.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Hassan Krayem, "The Lebanese Civil War and the Taif Agreement,” Beirut, American University of Beirut, May 23, 2003, http://ddc.aub.edu.lb/projects/pspa/conflict-resolution.html [last accessed on January 3, 2015].

- 11. Ariel Keysar and Barry A. Kosmin, Secularism, Women and the State: The Mediterranean World in the 21st Century, Hartford, Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture, 2009, p. 72.

- 12. Ibid.

- 13. The relationship between church and state manifested in institutionalized religion is in stark contrast to the sociopolitical rise for a civil religion in the political context where there is a separation of church and state.

- 14. Christenson and Wimberley, “Civil Religion and Religious Identities,” Sociological Analysis, 42(2), 1981, pp. 91-100.

- 15. Keysar and Kosmin, 2009, op. cit.; See also Robert Bellah, “Civil Religion in America,” Daedalus, 96(1), 1967, pp. 1-21.

- 16. See Daniela Rosche, “Close the Gap: How to Eliminate Violence Against Women Beyond 2015,” Oxfam GB, 11 March 2014, available online at: http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/bn-close-gap-vi... [last accessed on January 30, 2015].

- 17. See Shireen Hassim for an extensive analysis on inclusionary politics for women in South Africa and the usage of a gender quota to mobilize women into decision-making spheres; Shireen Hassim, “Terms of Engagement: South African Challenges”, in Feminist Africa, 2005, African Gender Institute, University of Cape Town, Issue 4, 2005, availale online at: http://agi.ac.za/sites/agi.ac.za/files/fa_4_feature_article.pdf [last accessed on January 28, 2015].

- 18. Adila Abusharraf utilizes data from OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) of gender disparity in economic development to base a correlation between gender inequality in Muslim communities where Islamic jurisprudence (as an extension of religious institutions) is a cause for constraining women from participating in economic activities; Adila Abusharaf, “Women in Islamic Communities: The Quest for Gender Justice Research,” Human Rights Quarterly, 28(3), 2006, pp. 714-728.

- 19. Constitution of the Republic of Lebanon, 1926, and further amendments, 1995, available online at: http://www.presidency.gov.lb/English/LebaneseSystem/Documents/Lebanese%20Constitution.pdf [last accessed January 14, 2015].

- 20. Hassim, op. cit.

- 21. Suad Joseph & Joseph Stork, “Gender and Civil Society: An Interview with Suad Joseph,” Middle East Report, 183, 1993, p. 25

- 22. Abusharraf, 2006, op. cit.

- 23. Hussein Abdallah, “Lebanese rivals set to elect president after historical accord.” The Daily Star, English, May 22, 2008, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Lebanon-News/2008/May-22/51877-lebanese... [last accessed on January 2, 2015].

- 24. Implications of the Doha agreement for this paper are not studied, but rather the language of this agreement serves as evidentiary de facto law for interpretation of Article 20.

- 25. Security Council Report, Retrieved from http://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-C... [last accessed on November 1, 2014].

- 26. Suad Joseph, “Gender and Citizenship in Middle East States,” Middle East Report, 198, 1996, p. 8.

- 27. Lara Khattab, Civil society in a Sectarian Context: The Women’s Movement in a Post-War Lebanon, Beirut, Lebanese American University, 2010, p. 78.

- 28. Ibid., p. 91.

- 29. According to the NCLW website, the organization is the only recognized body by the state of Lebanon as the “mechanism responsible for managing women’s advancement and gender equality in; it reports directly to office of the Prime ministry” (Who is NCLW? Retrieved from http://www.nclw.org.lb/Faq [last accessed on January 19, 2015]).

- 30. The NCLW is a transplant of the National Committee for the Follow up of Women’s Issues (NCFUWI). The NCFUWI consisted of men and women who prepared for the Fourth World Conference in 1995. Subsequent to the creation of the NCLW, NCFUWI became a women’s advocacy NGO under the acronym of CFUWI .The NCLW overtook administrative and organizational duties in 1998 under law 720, which “entrusts missions” of consultation, liaison and coordination, and execution concerning Lebanese women’s affairs. (Who is NCLW? Retrieved from http://www.nclw.org.lb/Faq [last accessed on January 19, 2015]).

- 31. Khattab, 2010, op. cit., p. 91.

- 32. Ibid.

- 33. See Riwa Salameh, 2014, for an in-depth, critical assessment of NCLW’s top-down structure, especially on the organization’s bias and classist features.

- 34. Lebanon signed the U.N. Convention in 2000, with reservations against article 9 (2) and articles 16 (1) (c) (d) (f) and (g) (Division for the Advancement of Women. (2009). Declarations, reservations, and objections to CEDAW (UN Publications). New York: United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/reservations-country.htm#N36 [last accessed on January 19, 2015].

- 35. Sidney Tarrow, The New Transnational Activism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 73..

- 36. Khattab, 2010, op. cit., pp. 140-143.

- 37. Tarrow, 2005, op. cit., p. 61.

- 38. Reservation on article 9 include (2): States Parties shall grant women equal rights with men with respect to the nationality of their children.

- 39. Reservations on article 16 include: (1) States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in all matters relating to marriage and family relations and in particular shall ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women: (c) The same rights and responsibilities during marriage and at its dissolution;(d) The same rights and responsibilities as parents, irrespective of their marital status, in matters relating to their children; in all cases the interests of the children shall be paramount; (f) The same rights and responsibilities with regard to guardianship, wardship, trusteeship and adoption of children, or similar institutions where these concepts exist in national legislation; in all cases the interests of the children shall be paramount; (g) The same personal rights as husband and wife, including the right to choose a family name, a profession and an occupation;

- 40. Reservation of paragraph 2 in reference to paragraph 1 of article 29: (1) Any dispute between two or more States Parties concerning the interpretation or application of the present Convention which is not settled by negotiation shall, at the request of one of them, be submitted to arbitration. If within six months from the date of the request for arbitration the parties are unable to agree on the organization of thearbitration, any one of those parties may refer the dispute to the International Court of Justice by request in conformity with the Statute of the Court. (2) Each State Party may at the time of signature or ratification of the present Convention or accession thereto declare that it does not consider itself bound by paragraph I of this article. The other States Parties shall not be bound by that paragraph with respect to any State Party which has made such a reservation.

- 41. Randa Berri, wife of long standing Speaker of Lebanon’s Parliament and sectarian warlord, Nabih Berri, “went as far as to deny that domestic violence existed in Lebanon, and that it was only a problem in the West…this statement came after pressure was exerted by religious figures to drop the issue [of domestic violence]” (Elinor Bray-Collins, “Muted voices: Women's rights, NGOs, and the gendered politics of the elite in post-war Lebanon” (Doctoral dissertation), Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database (UMI No. MQ78094), 2003 [last accessed on January 19, 2015], p. 95).

- 42. See Scholars such as Mona Leena Krook, Valentine Moghaddam, Drude Dahlerup, Mark El-Makari, Marguerite el-Helou, and Kamal Feghali.

- 43. Baer, T., Al Jazeera English, Doha, Qatar, May 29, 2009, available online at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sIGmmuK1OzM [last accessed on January 2, 2015].

- 44. See Joseph, 1996, op. cit.

- 45. Civil society organization ABAAD and International Medical Corps hosted a “16 Day of Activism,” which included solicitation from religious leaders to unite and call for “an end to gender violence in Lebanon.” (Media ads can be accessed here: https://internationalmedicalcorps.org/sslpage.aspx?pid=2473#.VK9i1lq6TBE).

- 46. Since 20102, women’s advocacy group KAFA has been working along with members of government to implement a framework for ISF officials to recognize and address family violence. Most poignantly, KAFA’s campaign with the Lebanese State means to broach trust between “women victims of violence and the ISF”. This statement recognizes that, to fulfill a UN action to recognize VAW, where the Lebanese State refuses to enact a gendered law, the responsibility to address gender violence has again shifted to the sphere of civil society. See KAFA’s website for information regarding the women’s advocacy group’s campaign, “We have a missiong” “If you’re threatened, do not hesistate to Call 112”: http://www.kafa.org.lb/kafa-news/68/launch-of-the-campaign-we-have-a-mis... [last accessed January 28, 2015].

- 47. Nadine Elali, “Lebanon’s Policewomen,” NOW, English, 20 May 2012, available online at: https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/reportsfeatures/lebanons_policewomen1 [last accessed on January 28, 2015].

- 48. See IWSAW’s Al-Raida publication from Summer/Fall 2009 for debates on whether a quota system could in effect round out a political system into a democratic institution.

Sandy el-Hage has an M.A. in International Affairs from the Lebanese American University. Publications include a thesis paper entitled Transnational Activism in Lebanon’s Women’s Movement (2013) and an article in Al-Raida entitled , Nasawiya: A New Faction in the Women’s Movement (2013), on grassroots feminist organizing. On-going research interests include women’s issues, the crux between social movements and contentious politics, political structures, and reformist policies for civil and women’s rights.

Email: sandy.hage@gmail.com