Gender politics in Lebanon and the limits of legal reformism (En-Ar)

Women organizations in Lebanon have a long history of struggle towards gender equality. Perceptions concerning the achievements and status of women in Lebanese society suggests relative progress on issues related to rights and gender equality. This paper proposes an analysis of the status of women in Lebanon based on various indicators highlighting women’s participation in politics and decision-making processes and examining gender equality from the legal perspective and in terms of women’s economic status. It also looks into women’s achievements in terms of gender equality, reviewing some strategies adopted to enhance women’s status in Lebanon and highlighting their limits in the particular Lebanese socio-political context. *This paper is available in Arabic as a pdf file - pdf هذه الورقة متوفرة باللغة العربية ويمكن تحميلها كملف

To cite this paper: Riwa Salameh,"Gender politics in Lebanon and the limits of legal reformism (En-Ar)", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2014-09-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSR.001.007

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/ar/paper/gender-politics-lebanon-and-limits-legal-reformism-en-ar

It has become common in Lebanon to hear statements such as "men should be asking for their rights," expressed by men through a joke or by waging an endless conversation. Such sentiments were made public by Lebanese MP Ali Ammar, during the parliamentary session on the recent family violence1 law, who said: "We call on women's organizations to draft a law that protects men from violence."2

Such statements, regardless of the level of their seriousness, imply that women are currently enjoying a life free of discrimination and violence and insinuate that gender equality has been achieved and became a question of the past.

Indeed, the extensive amount of violence, lack of justice and transparency, corruption, lack of workers rights, and violations against freedoms of speech are denying all Lebanese citizens their human rights. But this should not mean that gender equality has been realized; only that it takes a back seat. However, it reflects a transformation in women’s status and role in society.

This paper will analyse the status of women in Lebanon, based on various indicators highlighting women’s participation in politics and decision-making processes, with a focus on the structure and the responses of women’s organizations when addressing discrimination against women. It aims to identify challenges that hinder the achievement of gender equality by examining gender equality from the legal perspective and in terms of women’s economic status. Finally, the paper proposes an analysis of women’s achievements in terms of gender equality, reviewing some strategies (and their limits) adopted to enhance women’s status in Lebanon in the particular Lebanese socio-political context.

1. Women’s status in Lebanon

A) Women: Legally second-class citizen

Lebanon ratified the Convention on the Elimination all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 1996. The step was considered a major achievement towards equality by women’s organizations who had struggled for the Convention's adoption. However, reservations by the Lebanese government – on Article 9, Paragraph 2, and Article 16, Paragraphs 1(c, d, f, g)3 – refuted the purpose and objectives of CEDAW. The rejected articles related to personal status laws and nationality rights of women citizens. Through the reservations, the Lebanese state continued to deny women the enjoyment of the same rights as men in instances of marriage, divorce, and all family matters and upheld the ban on Lebanese women from passing their nationality to their husbands and children. The reservations intended to maintain the current personal status law, which is under the mandate of religious courts, rather than civil courts.

According to some women’s organizations, these reservations are an obstacle towards concrete advancement in women’s rights. For example, KAFA (enough) Violence & Exploitation (KAFA), the Collective for Research & Training on Development-Action (CRTD-A), the Lebanese Women Democratic Gathering (RDFL), and several other organizations launched a campaign protesting the Lebanese state's promotion of patriarchal authority over women's rights by preserving the discrimination inherent in religious personal status laws.

What is wrong with personal status law?

As it stands, the Lebanese constitution delegates all personal status laws to sect-specific religious courts. All matters related to family (divorce, marriage, inheritance, custody of children) remain the exclusive responsibility of religious institutions, which subscribe to the notion that men should be at the head of the family unit, hence preserving the inferiority of women under the law.

Inspired by religious discourse, this legal structure necessarily places women as second-class citizens, treating them as minors in decisions related to governing their own lives. Suad Joseph describes how citizenship in the Arab world is gendered through nation, religion, family, state, and the individual:

"Most constitutions of Arab states identify the basic unit of society as the family. This suggests the masculinization of citizenship in Arab states is tied to a culturally specific notion of the citizen as subject. The Arab citizen subject is seen as a patriarch, the head of a patriarchal family, legally constituted as the basic unit of the political community who accrues rights and responsibilities concomitant with that legal status."4

In Lebanon, Marriage, divorce, inheritance, child custody and alimony are governed by religious courts, which favor men and represent their supreme interests. Religious courts apply arbitrary rules on women, subjecting them to various levels of inequality in comparison to men. For example, women from non-Christian sects inherit less than their male counterparts and the age of marriage for women is lower than that of men across all sects. Men are considered the sole decision makers in matters of divorce, in particular according to Muslim sects. Additionally, the prohibition of divorce in Catholic sects ultimately favors men over women, due to the unequal dominant social and economic order.

This reality cannot be ignored, as people are basically unable to practice social life, relations, and personal choices outside of the license of sectarianism. These aspects of social and personal practices are all centered around the notion of the family unit and governed by its dynamics. They are ultimately shaped by the interests of the ruling religious and political establishment, where the family is defined by law through male kinship. Hence, the Lebanese state denies a wide variety of rights for citizens, which fall outside the sectarian structures. The personal status law also discriminates among and between women (of different confessions), through disparate statuses and conditions set by different religious courts, whereby the personal status of women citizens are accorded according to their religious denomination.

The delegation of personal status to religious jurisprudence compromises the safety of women, complicates the establishment of protection mechanisms, and often legitimizes violence against women. Thus, it could be inferred that the Lebanese state denies its citizens their individual constitutional rights, by allowing sects to establish their own religious courts. And since men are the heads of families according to religion, women will remain at the bottom of this hierarchy. Consequently, this implies that discrimination is legalized and protected by law, as religious ideas and discourses – which often discriminate against women and define gender roles according to their particular understanding – are not merely personal beliefs, but applicable laws with a direct impact on peoples' lives. This issue will be discussed in details below.

Discrimination in Civil Law and the Penal Code

Discrimination against Lebanese women extends to the penal code. Nationality laws deprive women of the right to pass the Lebanese nationality to their families if they choose to marry a non-Lebanese citizen. Moreover, articles related to rape in the Penal Code exempt rapists from penalty if they simply declare their intention to marry the victim (Article 522)5 and criminalize rape while clearly excluding incidents of rape and forced intercourse practiced by a husband on a wife (Articles 503 and 504).6

Moreover, Article 5417 of the Lebanese Penal Code criminalizes abortion and effectively denies women their right to control their bodies. However, abortion is not considered criminal if it is with the intention of maintaining a woman’s 'honor' (Article 545)8, even in the case of forced abortion inflicted on women without their consent by male family members (articles 542 and 543)9. According to articles related to abortion, women's bodies and unwanted pregnancies can be subject to decisions by (most probably male) family members, but not by women themselves.

This situation forces women to compromise their protection by undergoing so-called 'back-alley' abortions, where it is impossible to hold accountable the doctors who performed the surgery due to its criminalization. Nermine el-Horr recounts the story of a woman who had to undergo such process, in the article, "Secret abortion market: poor women are the victims." Horr explains how poor women in particular are facing serious obstacles and safety issues if they wished to abort an unwanted pregnancy.10

Adultery laws reveal more gender-based disparities in terms of punishment and scope. Articles 487 and 48811 of the Penal Code specifies a penalty from one month to one year, when a man commits adultery in the marital household or in public. On the other hand, women are penalized up to years in any situation considered to be adulterous. Furthermore, while a woman’s extramarital partner is not considered a guilty party, a man’s extramarital partner (or his mistress) is penalized.

Despite affirmations by the Lebanese state concerning equality between all citizens, as set forth by the Constitution of the Republic of Lebanon, it is clear that civil laws and personal status laws are equally gendered, with a clear and declared bias against women.

The next section will examine how this discrimination applies in the workforce and working class women in particular by examining the socio-economic situation of women and the value of their work.

B) Women: the invisible and exploited working class

The vast majority of workers, if not all, are subjected to labor exploitation in one-way or another. But women seem to face the brunt of this discrimination. Such observations are diluted by official labor statistics, which claim that only 23% of women above 15 are part of the formal labor force.12 By excluding the informal sector, labor statistics imply that most women are not economically active. However, female exploitation cannot be measured through a simplistic assessment of wages and benefits in the formal workforce. The vast majority of working women are invisible, employed in the informal sector or in the household. Tasks performed in the household should be considered part of the social care sector, defined by Seiko Sugita as referring to

"[...] work that involves connecting with other people and trying to help them meet their needs, such as caring for children, the elderly, and sick people. Teaching is also a form of caring labor, whether it is paid or unpaid. Social care is a unique type of work. Since social care does not generate financial resources and does not contribute to economic production as measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the classical definition of work has not considered it as proper work."13

Patriarchal society sets a double standard by not considering labor within the household to be economically valuable. By default, this denies the value of the majority of women labor, as patriarchy limits women’s primary labor role to the family sphere, and refuses to acknowledge the economic value of this type labor. Sugita shares the findings of a survey of 2,797 households regarding division of household labor.

"According to a cross-sectional survey of 2,797 households in three communities in Lebanon, a clear division of household labor was apparent, with more than 70 percent reporting that the wife performed in-house chores such as cooking and washing clothes and dishes. The analysis shows the correlation between the lack of involvement of the husband in housework and the wives’ psychological distress, marital dissatisfaction, and overall unhappiness. In comparison with wives whose husbands were highly involved in housework, wives whose husbands were minimally involved were 1.60 times more likely to be distressed, 2.96 times more likely to be uncomfortable with their husbands, and 2.69 times more likely to be unhappy.

"Among the 16 households where the main caregivers are married, only one household responded that the husband is the main executor of the non-care household tasks such as cooking and cleaning. In 15 households, women are the ones most responsible for the execution or supervision of the housework. Indeed, only 9 out of 22 people interviewed in the context of this study thought that men should take more responsibility in carrying out household tasks. In many cases, the lack of participation and contribution is explained by the long working hours."14

Although the family unit is positioned as the frontline caregiver and takes over the social and health responsibilities of the inadequate State, women’s labor in the family sphere remains unrecognized and is considered a “duty” and “responsibility”. Consequently, women carry the burden of numerous caregiving services to children, older persons, and family members with special needs, which otherwise should be the burden of the State. These long working hours, which are often trivialized, are spent managing and performing tasks in the household, free of charge.

"Social care in Lebanon is often considered a family and private matter, in which the state is traditionally reluctant to intervene. In fact, the various kinds of household chores are all considered as a woman’s job. Moreover, social rituals within the extended family structure are usually time consuming and labor-intensive, and constitute thus an additional burden to the care needs of the nuclear family."15

In our society, women receive no compensation for working in these areas:

"Unpaid caregiving and assistance activities include housework (cooking, cleaning) and care for people (children's hygiene, assistance to elderly and the infirm) performed in homes and communities. They contribute to well-being and economic growth through the reproduction of a sound and productive workforce, able to learn and innovate. In all economies and cultures, women bear the greatest burden of unpaid care. In addition, it is estimated that if a monetary value is assigned to this work, it would represent between 10 and 39 percent of the GDP."16

Low-paid Migrant Domestic work

In addition to the estimate above, it is important to note the high numbers of migrant domestic workers who perform such tasks at very low wages in Lebanon. On this matter Seiko Sugita notes that:

"Social care is a growing market where foreign housemaids supply their labor for the Lebanese middle class (Jureidini, 2003)... The standard remuneration is on average five thousand pounds (3.5 dollars) per hour for Lebanese and Palestinian women and freelance foreign workers. This type of freelance care service is attractive to many households where there is not enough room for a live-in domestic worker and where there is no need for a full-time domestic worker."17

Although this may be an economic estimate of the cost, it falls far short of the actual economic contribution of unpaid household services, as migrant women represent another exploited social class governed by discriminatory contract called the sponsorship system. According to a study by KAFA:

"The 'sponsorship system' in Lebanon is comprised of various customary practices, administrative regulations, and legal requirements that tie a migrant domestic worker’s residence permit to one specific sponsor in the country. Migrant domestic workers are excluded from the Lebanese labor law, denied their freedom of association, and not guaranteed freedom of movement."18

The non-recognition of women’s domestic work as an economic value and the exploitation of migrant domestic workers relieves the state from the burden of providing those services, placing them on the backs of women.

Yet, women’s unpaid labor is not restricted to domestic work. According to a study conducted by CRTD-A:

"Women represent 34% of the total permanent family work force in agriculture in unpaid labor...They provide considerable labor to the tobacco crop. They also collect wood for energy and nearly 40% of remote rural areas require women to fetch water from source or wells. Many women are hired to perform seasonal agricultural work, particularly during harvest time, receiving low salaries."19

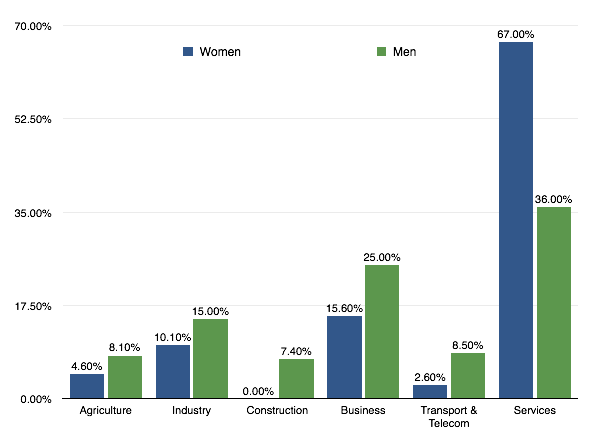

Figure 1: Labor force by economic sector, in percentage of labor force by gender

Source: UNDP 2007 Household Survey

Women’s labor in the agricultural sector is also invisible. According to the same study "agriculture employs 12% of the Lebanese workforce, ranking it last among Lebanon’s economic sectors. Women participate significantly in agriculture but mostly as invisible labor."20

Women participating in paid labor also face economic exploitation. At least 57% of female employment is informal,21 unregulated by the labor law. This sector is mainly characterized by lack of safety, long working hours, arbitrary expulsion, and lack of social security. It is also important to note that the majority of NGO workers are women, employed in time-limited project and where donors fail to take into consideration the need for budget lines related to social security and insurance. Furthermore, the NGO sector lacks clear salary scales and workers are denied the ability to enjoy salary raises in a systematic manner.

Carole Kerbage shares the stories of women NGO workers who expressed frustration about their working conditions:

"Maya (not her real name) has ten years experience in civil society organizations, during which she moved between seven different organizations (the longest period she spent at one organization was a year and a half). Throughout those years she only received social security benefits for two years, therefore she was deprived of a large chunk of end of service indemnity. She admits that she has recurring anxiety about funding running out or the project ending."22

From a different angle, women are also victims of sexual harassment and mistreatment while performing their work. However, figures stating the level of sexual harassment do not exist due to social constraints and the culture of victim blaming. This prompted Legal Agenda (a judicial watchdog NGO) to draft a law addressing sexual harassment in the workplace. The proposed regulation suggested that:

"Physical or psychological harassment in the workplace constitutes a threat to the right to work, the right to privacy, the mental health of workers, their physical integrity, the right to non-discrimination, and so on. Despite the graity of those acts, Lebanese legislations are still free of any prohibitive articles, leaving individuals vulnerable to harassment without effective protection. This gap is aggravated by the fact that harassment impacts the most vulnerable categories of wage earners, including workers conducting domestic and agricultural services, who do not benefit from protection under the labor law."23

Although Lebanon is considered a 'progressive' country in comparison with its neighbors, women's sexuality is still considered a taboo. Society ties family honor inextricably to women’s sexuality. Revealing an incident of sexual harassment would compromise her safety, reputation, and advancement in life, not to mention the physical and psychological consequences of such an incident.

Collectively, women also face discrimination and inequality in wages, benefits, and sick leave, compared to their male colleagues. They are paid 27% less than their male counterparts for the same type of work.24 Likewise, they have limited opportunities in accessing decision-making positions. Moreover, women are limited to low–income care-provider jobs, which reinforce stereotypical gender roles for the most part, and the great majority of women are employed in the services sector.25

In short, the majority of women suffer from various forms of exploitation, including unvalued domestic work and employment in the formal and informal sectors. This exploitation is institutionalized through the non-recognition of economic value of domestic work and invisibility in the labor code, namely for migrant domestic workers. Furthermore, the total absence of state policies related to protecting women in the workplace could lead to hesitation in joining the workforce. The Lebanese state turns a blind eye to sexual harassment and the exploitation of women in terms of wages and social security, in both the formal and informal sectors. The governance of personal status by religious institutions clearly stipulates that the man should be at the head of the family unit, which necessarily means that women’s work is always secondary in comparison to her 'duties' at home. Moreover, the educational curriculum is far from being gender-sensitive; rather, it contributes to sustaining the stereotypical image of women as mothers and caregivers.

C) Women’s political participation

In 1995, Lebanon participated at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing and agreed on the principle of equal access by men and women to power structures and decision-making bodies. Participating countries are obliged to abide by the recommendations of the final statement, which requires each country to set goals and implement measures to substantially increase the number of women in leadership. Women's organizations considered the conference to be a huge step towards women’s political participation. However, after almost two decades, this participation remains almost non-existent and Lebanese women are still excluded from decisions making positions.

Women’s organizations are constantly proposing a quota system for parliamentary elections to ensures a framework for such participation. However, this suggestion contains limitations in terms of achieving effective participation and, most importantly, ensuring a share for women in the decision-making process. Nevertheless, women's participation in parliament does not guarantee that women agendas will get through legislative bodies by default. In fact, MP Gilberte Zwein, a member in the joint committee discussing the draft law to protect women from family violence, did not support the demands of women’s organizations and her presence did not prevent the committee from distorting the content of the law.

Azza Baydoun gives a revealing description of the confessional system restricting women from access to political positions:

“In Lebanon, like any country that is governed by a patriarchal system, belonging [...] to a particular family is inherited through the male line of kinship (bloodline) [...] By contrast, a women’s lineage or affiliation changes through marriage, as does her sectarian, regional, and familial affiliation... Therefore, the appointment of males in decision-making positions [...] has clear benefits for all actors, whether political authorities, decision-makers, or recipients and beneficiaries, i.e. citizens under this system."26

It is quite clear that the patriarchal and sectarian nature of the state functions as an obstacle to women's presence in the political scene. Personal status laws are intimately tied to political nepotism, where the male head of families are also heirs to the political throne. The incident below illustrates an example of how such laws deny women access to politics.

In October 2013, the municipality of Nahr Ibrahim was disbanded. When the municipality president was asked about the reason, he answered that four out of nine municipality members resigned and the fifth, a woman, was no longer eligible for the position. A municipality is disbanded when a majority of its delegates resign. The fifth member, a woman, however, did not resign. She had married a man from outside of the village and therefore lost her affiliation with the village she was born and raised in and which she politically represented. Her political affiliation changed to that of her husband’s, effectively voiding her ability to represent her community. The minister of interior and municipalities decided to disband the municipality.27

Similarly and due to dominant patriarchal culture, women are unable to reach parliament or government, except in the absence of a male heir in the family. Doreen Khoury eloquently explains how this access can be denied, in her article Women’s political participation in Lebanon. She explains how all political blocs are linked to family allegiances and how "most followers accept that the leader’s son will inherit his position."28 This applies to women who joined the parliament after the death of male relative or the absence of the male heir which means in her opinion that the patriarchal construct in the family is replicated in the politics:

"The patriarchal construct of the family in Lebanese [sic.] is replicated in Lebanese politics. Political familism has been one of the major factors affecting the relationship between state and citizen. It is a two way process. Citizens depend on their families and extended families (i.e. kinship ties) to extract demands and privileges from the state and state actors deploy these ties to mobilize supporters and control sectors of the state. When the state fails to provide protection and resources to its citizens, they turn inwards towards their families, patriarchs and sects."29

Hence, even if the participation of a number of women in parliament or the government is achieved, the main challenge deterring women from accessing such institutions to put in place an agenda for women will remain untouched.

The following table illustrates women’s participation in decisions-making and the political scene in Lebanon in general:

|

Position |

Year |

Women’s participation |

|

Lawyers syndicate (Beirut-North) |

2010 |

0% |

|

Engineers syndicate (Beirut-North) |

2010 |

3 out of 31 members (9.79%) |

|

Doctors syndicate (Beirut-North) |

2010 |

6.25% |

|

Dentist syndicate |

2010 |

0% |

|

Pharmacist syndicate |

2010 |

25% |

|

Journalism syndicate |

2010 |

12.5% |

|

Editors syndicate |

2010 |

8.33% |

|

Political bureaus (political parties) |

2010 |

12-16% |

|

General managers-first degree (public sector) |

2010 |

13.3% |

|

Executive board of general union |

2010 |

0% |

|

Judges |

2010 |

42% |

|

Mukhtars [neighborhood mayors] |

2010 |

3.6 (148 out of 2570) |

|

Parliament |

2009 |

3.12 (4 out of 128) |

|

Government |

2009 |

2 ministers |

|

Government |

2011 |

0 |

|

Government |

2014 |

1 minister |

|

Municipalities |

2010 |

4.55 (520 out of 11425) |

Source: Azza Mroueh, intervention by Lebanese League for Women’s Rights (LLWR) at the Consultative Workshop for Civil Society organizations in the Arab Region on the progress made in the implementation of the Declaration and the Beijing Platform for Action after twenty years, 12 August 2014.

The above table, although a mere snapshot of women's participation in formal politics, demonstrates that women are far from achieving equality and are held back from decision-making positions and the political scene in general. The question of representation was discussed above, in relation to its links with the patriarchal family structure. This situation is replicated, however, in the dynamics of representation in other types of institutions.

Out of all the professional and representative positions in the political class, the only place where women are close to parity is in the judiciary, as 42% of judges in higher courts in 2010 were women and were expected to reach 60% in 2011.30 Although UNDP considers the figure to be "a promising progress in women political participation," the situation could be attributed to fierce competition in the litigation sector and the prevalent "old-boy" networks of prominent lawyers, leaving the judiciary – and its merit system – as the only channel for many women with law degrees to actually practice law. This exception, which proves the rule, becomes even more apparent when compared with the percentage of women in the leadership of bar associations, which are sustained by the same pool of professionals.

Generational questions also play a role, especially since it is only now that post-civil war generations have begun to assume influential positions. However, in this particular case and several other professions, women also constitute a majority of university graduates in the field, especially from the Lebanese University, which is reserved for the poorest social segments.31 Despite equal access to education and improvement in the opportunity to join professions on the formal level, women – especially less privileged women with less access to ruling structures – tend to become invisible and have to confront another glass ceiling in their professional associations.

2. Responses and challenges

The above situation raises questions about the effectiveness and impact of responses and tools used by women's organizations regarding women's political participation. This section analyses women’s organizations responses to the aforementioned status, highlighting their achievements and influence on women’s lived experiences as well as their contributions to gender equality. It also looks at the challenges and obstacles that play an essential role in hindering the realization of gender equality.

Considering the long history of the women's movement in Lebanon, gains in terms of achieving gender equality remain lacking on all levels. The reforms realized so far have had little impact on women’s lives and remain far from fulfilling women’s ambitions in enjoying life free of violence and discrimination. But, what makes gender equality so hard to achieve despite the long years of struggle?

A) An alternative response?

In its coverage of the 2013 International Women’s Day (IWD) march, al-Liwaa newspaper chose to focus on the status of some marchers as a measure of legitimacy. The march itself was characterized by shy attendance and only attracted women engaged in women’s organizations – similar to other protests calling for women’s rights, which failed to adequately mobilize the vast masses of women. The newspaper wrote:

"In this context, the Gathering for Women Youth and Civil Associations organized a national march to achieve equality and full citizenship for women. It was attended by the president of the National Commission for Lebanese Women Ms. Wafaa Sleiman represented by the former minister Wafa al-Diqa Hamadeh and Dr. Fadia Kiwan. The former ministers Mona Ofeish and Pierre Dakach and a number of professors, women’s organizations, human rights committees, and civil society organizations also participated in the march."32

What is notable about this piece of news is that it is repeated every year, giving the impression that IWD is merely a yearly celebration by the same group of women presenting the same demands listed the article year after year. This observation does not intend to undermine women’s activism and mobilization or other existing campaigns. Rather, it attempts to raise questions about failure to mobilize wide sections of women on issues with a direct impact on their lives. However, this inability to attract a strong political base of women in such protests is an indication of the challenges faced by women’s organizations in relating with other women who do not belong to an elite community.

On the other hand, the 2014 demonstration attracted around 5,000 persons demanding the endorsement of the law to protect women from family violence. The action reflected specific demands set by the organizers (led by KAFA) as well as calls by feminists to end violence and discrimination against women. The diversity of the participants and the significant response, in comparison with the recent past, indicated an ability to build a far-reaching movement calling for women’s right.

Although the 2014 IWD demonstration was the first to be organized by KAFA or similar organizations, it stood out due to the absence of official participation by mainstream political parties or 'prominent' figures in society. Rather, the call was for people to raise their voices and pressure the parliament to endorse the law related to violence against women and ensure specific protections for women.33

The above is merely an indicator of the ability of women's organizations to create a wide movement and mobilize people once IWD stops being a mere commemoration of a day and adopts an agenda, to which people, particularly women, could relate. However, this ability is challenged by organizational structures and limitations in terms of engaging with the public and providing spaces for building alliances and where people could contribute to decisions-making, strategizing, and setting actions plans and priorities for women’s movement.

|

A brief history of women’s organizations in Lebanon The era of al-Nahda, characterized by associative effervescence, witnessed the emergence of many women's organizations in Lebanon. Academics identified what has been called the first wave or first generation of women organizations, which were mainly charity oriented, much like the rest of the existing associative organizations during that era. The 1960s and 1970s saw the birth of a second "wave," which burgeoned from left-wing groups; this generation adopted specific women-centered issues.34 During the 1990s, a third wave of organizations – created in the aftermath of international conventions (CEDAW, 1979; Beijing, 1995) – underlined a new trend of “professionalization” of women activism in Lebanon.35 More recently, the 2000s, and in the vein of alternative globalisation mobilizations, witnessed the emergence of groups presenting themselves as "radical," and which focused their demands on gender identities and sexual rights, with an increasing trend of health service provisions shifting away from right based and advocacy mobilization.36 |

The following section will elaborate on some structures and organizational methods adopted by women's organizations, National Commission for Lebanese Women (NCLW), the Lebanese Council for Women (LCW), RDFL, KAFA, and CRTD-A.

B) Top-down structures

NCLW was established by the Lebanese state in 1996 in accordance with the 1995 Beijing Resolution. It was formed of official and non-official bodies and structured to have the First Lady as president and the parliamentary speaker's wife and the wife of the prime minister's wife as vice presidents, in tandem with the Lebanese sectarian political structure.

Such state-driven structures, evident in the majority of reactions to Beijing, cannot be seen as credible or welcoming for women, who are suffering from the sectarian system and forced to delegate their personal matters to religious institutions. Thus, a conflict of interest has already been established in terms of the commission’s agenda. On one hand, this commission is mandated to monitor the application of the CEDAW convention and enhance gender equality. On the other, it is directly affiliated with the sectarian system, which continuously perpetuates gender discrimination and conflicts with the CEDAW convention itself. Furthermore, the structure clearly denies the access of women to leadership positions and limits such access to a small group of women from the political class.

LCW – an umbrella of more than 100 organizations37 – had been founded 1952 as a result of the merger of two bodies, the Lebanese Arab Women’s Union, founded in 1920, and the Solidarity of Lebanese Women association, founded in 1947.38 LCW follows a top to bottom structure, compromising women’s agendas in favor of sectarian benefit. Lara Khattab eloquently expresses this issue in her thesis entitled Civil Society in a Sectarian Context: the Women’s movement in Post-War Lebanon:

"The General Assembly, the decision-making body which is also responsible for the election of a new administrative committee, is almost totally colonized by confessional and sectarian associations. Hence, the same council which sets for itself the goal to empower women brings together the largest number of associations that have the highest stakes in alienating women. Most of these associations are headed by a religious or a sectarian leader, are oriented towards service provision for their narrow confessional communities operating under a system of religious patriarchy."39

Nonetheless, this is not necessarily the case for all women’s organizations, as many of them, including KAFA, CRTD-A, and RDFL, to name but a few, refuse to be part of LCW and adopt a non-sectarian agenda.40 The top to bottom structure, however, also denies women access to decision-making and leadership positions in those organizations, despite this structural distinction. For example, although RDFL is structured as a member-based organization active throughout the country, its ability to mobilize women on political demands remains limited, largely due to the non-circulation of leadership. For instance, Wadad Chakhtoura remained at the head of the organization from the 1980s until her death in 2007.

By contrast but with a similar effect, KAFA and CRTD-A are led by a professional leadership, which relies on performing daily tasks by hired staff, which is not heavily involved in strategic planning. This structure draws distinct lines between women professionals advocating for women’s rights, their staff, and women "beneficiaries." In effect, beneficiaries are often seen in the position of victims, rather than women who share the same cause.

These hierarchical patterns turn women organizations into exclusive spaces for experts and professionals, leaving no room for other women, especially working class women, to join the decision-making and strategic planning process. Likewise, women are turned into victims, rather than being part of a platform where women’s voices and experiences can be raised and shared.

This particular situation is explained by Nisrine Mansour in her thesis Family Law and Women's Subjectivity and Agency in Post-conflict Lebanon:

"The shift towards service delivery with the VAW [violence against women] approach created new expertise roles for activists as translators of knowledge on gender equality in family law. It also included professional staff as new operational translators of this knowledge. As discussed below, this division of labour worked in tandem to further marginalize women’s participation in collective action."41

Mansour also shares her experience at a feminist conference she attended:

"One example is the conference that I participated in during my fieldwork on the achievements and challenges of the feminist movement in Lebanon. In one of the discussions, several feminist activists lamented the fact that the burden of collective action has become increasingly too big to bear, as there the numbers of new feminist activists joining women groups was very low. The discussion between long-standing activists and other younger members of the audience explained the conundrum of the ‘feminist activist’. Two feminist activists gave different explanations. The president of LWNGO5 found that there was 'low commitment by young generations to the issues of women’s rights.' The president of LWNGO3 rather attributed it to the 'burdens of economic constraints and the domestic pressures that women face by their family obligations' (Fieldnotes 2005). These two explanations framed individuals – and primarily women – as either unconcerned or constrained, but in both cases defaulting from the ‘activist’ role. While the discussion went on along these lines, an unaffiliated young woman participant asked to speak. She explained openly that she and her friends are interested in working on women’s issues, but they feel 'crowded out by long standing members in rigid organizational structures' (Fieldnotes 2005). The young woman’s views pointed to a sense of exclusion that individuals might have within feminist circles."42

In conclusion, women organizations are still unable to establish a mass movement that can actually push for gender equality. This failure is mainly due to their top to bottom structures, affiliation with the sectarian patriarchal system – as with NCLW and LCW, or to the dichotomy of experts and beneficiaries – as with KAFA, CRTD-A and RDFL.

Organizations like KAFA, CRTD-A, and LWDG are considered influential bodies, which confront the confessional system by demanding a civil law for personal status, nationality for Lebanese women’s families, and taking part in demands for civil marriage. Yet, the lack of leadership circulation, and the elitist distinction based on expertise causes the exclusion of women, in particular younger women, from accessing decision-making positions. NGOization, however, does not merely apply to Lebanese women’s organizations. It is a phenomenon that characterizes contemporary civil society organizations around in the world. Ultimately, the process tends to imprison women’s organizations in elite circles and such structures replicate the hierarchical patriarchal system, in terms of using its tools as means of change instead of creating a different model of peer organizing.

C) Limits of legal reform under sectarian laws

Recently, strategies by women's organizations began focusing on adopting advocacy campaigns through engaging with decision-makers and governmental institutions, in the aim of achieving reforms leading to the enhancement of the situation of women. This process, however, has imposed long-term negotiations with these institutions, where key demands would be transformed, distorted, and eroded in a manner that compromises the main objectives. Condemning them to remain governed within sectarian family law, these distortion actually tighten the noose around women’s necks, as will be elaborated below concerning campaigns engaging with religious leaders.

In the first eight months of 2013, ten women were killed by their sons, fathers, or husbands.43 Throughout the same year, 450 cases of family violence were documented by KAFA alone. The question of protection came to the forefront through women who began breaking the silence around the issue of family violence. Their stories revealed that religious courts are practicing injustice towards women in cases of divorce and custody and even incidents of severe violence. Such voices deemed religious courts as incapable of providing protection. Their role in such incidents was seen as enhancing and legitimizing the status quo, by imposing silence on women and insisting on considering family violence as a private matter and religious taboo.

In 2007, lack of protection under the current mandate of religious courts dealing with family issues prompted KAFA to spearhead the "Draft Law to Protect Women from Family Violence." The proposed law did not merely criminalize all forms of family violence – physical, sexual, mental, verbal, and economic. It also included several regulations to protect women and girls inside the family, such as provisions on restraining orders, reporting violence, securing accommodation and/or medical expenses for victims, safeguarding the family privacy, and ensuring the establishment of family units in the Internal Security Forces (ISF).

However, despite the brutality of recent incidents of femicide, the Parliamentary Subcommittee of the Joint Parliamentary Committee studying the draft law to protect women from family violence failed to adapt the law as it was proposed by the national coalition. The non-partisan committee consisted of MPs Gilberte Zwein, Nabil Nicolas, the late Michel Helou, and former human rights defender Ghassan Moukheiber (Free Patriotic Movement), Ali Ammar (Hezbollah), Imad al-Hout (Jamaa Islamiya), Shant Janjanian (Lebanese Forces), and Samir al-Jisr (Future Movement). Their amendments, however, went on to distort the proposed content, through:

-

Broadening the scope of the law to cover all family members, which effectively de-prioritized women subject to family violence and dismissed the specific protection procedures highlighted in the draft law. For example, the text proposed by women's organizations had suggested that Public Prosecution would be responsible for following-up on women victims of violence. However, the subcommittee delegated this task to judges in chambers that are not available after working hours or on holidays, which practically suspends protection for women subjected to danger or violence outside working hours.

-

Considering marital rape as a "marital right," which is only criminalized in the event of physical harm; this introduced a precedent, where the religious concept of so-called “marital rights” was clearly stated in a civil law.44

-

Excluding children from the scope of protection, when custody does not belong to the mother, which is in line with personal status laws.45

The Parliamentary Subcommittee had been targeted by a counter campaign launched by Dar al-Fatwa (the highest Sunni religious authority in the country and regulated under the presidency of the Council of Ministers) and religious courts, which said the law – particularly marital rape – would destroy the family unit. The subcommittee, through MP Moukheiber argued that the law, by specifying protection from women alone, was in contradiction of Article 746 of the Lebanese constitution and discriminated against the remaining family members, such as children and the elderly.

These distortions invalidated the fruits of years of investment by women’s organization, which spent their resources and launched advocacy campaigns to convince the government of endorsing the draft presented to the Parliament in 2010. The bill was approved by the Lebanese parliament on April 1, 2014 and ignored KAFA reservations on the amendments. By doing so, parliament failed to consider the fact that the law had been originally designed to respond to women’s particular protection needs.

The Lebanese state's hesitance in acknowledging and addressing violence against women reveals its patriarchal nature, working hand in hand with religious institutions to preserve the status quo; they feed on each other to maintain their authority. The state benefits from religious institutions to regulate the family unit expected to fulfill the needs of individuals such as education, health, shelter, and so on. On the other hand, this allows religious institutions to maintain their authority on private life, with the state's backing. Although the original draft was endorsed by MPs by a show of hands, the circumstances of the the law to protect women from family violence and its final version are an indication of the direct influence of religious institutions in shaping legislation in Lebanon.

Moreover, Dar al-Fatwa's counter-campaign was organized by the Women's Committees and Associations Gathering for the Defense of the Family. In a statement issued in 2011, Mufti of the Lebanese Republic Mohamed Rashid Qabbani expressed his opposition to the draft law and claimed it was in violation of sharia. He said the proposal would lead to the destruction of the family and create conflict between civil and religious courts.47

These distortions, prepared jointly by the state and religious institutions did not deter the Resource Center for Gender Equality (ABAAD), however, from launching a campaign entitled "We Believe," in collaboration leaders of religious institutions, including the Mufti Qabbani. ABAAD stated in the campaign’s press release that:

"The active participation of religious leaders in this campaign is meant to reinforce the potential of building bridges between activists in civil society associations concerned with women's issues, on one hand, and religious leaders, on the other. Discussion on effective common grounds would remain open and ongoing in the scope of enhancing common efforts aiming to improve public interest and build a society that respects human dignity and Women’s rights, which both sides agree upon."48

“We Believe” campaign49 was a strategic component aiming to enhance the dialogue between religious leaders. According to ABAAD Director Ghida Anani in the closing press release of the campaign, this strategy started at a regional round table consisting of religious leaders from all confessions and discussed their role in ending violence against women. Moreover, this strategy seeks reforms in religious institutions as a new tool to infiltrate the sectarian system.50

The campaign intended to create a space in the religious realm to enhance women’s chances in attaining justice in the case of violence inside the family. However, it legitimized the authority of those institutions, whose main role is to protect the patriarchal and sectarian system, which continues to hold women hostage, considers them as inferior member in the family and benefit from the social and economic exploitation of women. Moreover, the reforms that would take place in this sphere would still have to follow the whims of religious authorities, who could manipulate such reforms when they start to threaten the status quo. These types of strategies, however, tend to perpetuate the existing sectarian structure.

It is interesting to note that such campaigns are attractive to donor organizations and receive huge amounts of funding. For instance, "We Believe" was funded by more than 10 donors,51 whose logos were plastered all over campaign ads addressing religious leaders and state institutions.

This poses a critical question about the role of funding policies in maintaining the current order and shaping the discourse and strategies of women’s organizations. Lara Khattab also tackled this issue. She highlights the “role of funders in reinforcing and maintaining the existing sectarian system [as] the main obstacle in achieving gender equality,” shedding light on USAID funding for a campaign encouraging participation in the 2010 municipal elections and arguing that:

"As is the case for the parliamentary elections, the municipal elections also involve kinship, confessional and sectarian structures. In this regard, the campaign for the new municipal councils is a minefield, and the electoral process is a battlefield where all weapons should be used to win the blessing of the patriarchal leaders. Hence, the increased participation of women in municipal elections does not ensure the adoption of a women’s rights agenda as winners will continue to act on the basis of sectarian and kinship affiliations rather than interest-based considerations. In this regard, funders’ encouragement for women to take part in the same system that deprives them of their rights as equal citizens strengthens the ideological legitimacy of this patriarchal and sectarian system."52

Concerning this trend, Khattab explains that the donor community adopts a non-confrontational stance concerning family law debates. She provides an example, where the European Commission refused a project proposal presented by LWDG, aiming to reform the personal status law.

Hence, women's organizations are not alone in bearing the responsibility for the marginal progress in terms of women’s lives. The lack of volunteer-based organizations and the transformation of activists into professional staff meant that women's organizations have become dependent on donor money to maintain their work and pay salaries. Donors will have the upper hand in drawing strategies and shaping the women’s movement, leaving the system, which aims at compromising gender equality and women's protection untouched, well-maintained, and legitimized.

D) Reclaiming history of struggle

A a consequence of women's activism being oriented by a group of elite or middle class women – like the leaders of NCLW, priorities, strategies, and policies adopted to achieve gender equality are set with a foundational class bias. The majority of women, the most vulnerable and marginalized ones, those who belong to the working class or working class families, have little or no say at all in shaping strategies and policies purported to represent their interests.

This alienation of marginalized women from the decision making process places the majority of women at a far distance from being interested in adopting the demands of the existing women’s movement. It also explains the movement's inability to mobilize on the ground. Women’s organizations are often frustrated with women's lack of awareness of their rights. However, they neglect to evaluate their own discourses, in line with multi-level discrimination and the class issue.

Women’s organizations often decide to approach other women with "awareness raising" campaigns and activities, which essentially confirms their elite status and superiority toward their political base. This approach often calls upon women to adopt a demand, discourse, or tool founded and elaborated by international standards and definitions of human rights and women’s rights. However, such tools and discourses may not be applicable to many women in their daily life. It is important to appreciate that women live under different circumstances and communities that shape the injustice they face. Thus, they must be given space to create their own tools and discourses in order to survive and resist the status quo. Notably, this is not categorized as activism, resistance, or struggle.

More than a century ago, "factory girls," the daughters of Lebanese peasants, responded to the unfair working conditions in factories, at the very beginning of the attempt industrialization in Mount Lebanon. They organized themselves according to their needs, using their own tools to achieve their goals. Such experiences tell us that women themselves are able to change their own conditions. It is also interesting to note that those women formed a kind of union to achieve better conditions. Moreover, this process led those women to challenge and rebel against other limitations and stereotypes imposed by society.53 This experience shows the importance of women's involvement in unions, particularly since the "factory girl" rebellions were probably the very first instances of industrial action in the country.

Ayman Wehbe captures such resistance in his article on factory women in the 19th century. He notes that:

“One hundred years ago, a working class movement was born among women who work at Lebanese factories, which turned their communities upside down. “A’amiah,” a name for factory girls, became a word that meant independence and struggle for change… The struggle of female factory workers to enhance their working conditions was combined with social independence. Mothers used to call their daughters ‘factory girls’ whenever they wanted to straighten their behavior. And neighbors used to bully men whose daughters work in factories for being ‘out of control.”54

Such experiences in organizing no longer exist or, at least, are not highlighted or documented enough as alternative methods of struggle or sources of knowledge. Women’s struggles to achieve equality are limited to the representation, priorities, and strategies of women’s organizations, particularly NGOs.

Conclusion

Women's access to protection and equality in Lebanon remains limited. The presence of personal status law – governed by the various sects – is an actual hindrance to all types of reform aiming at achieving a better position for women. This law stipulates that women are more than often subordinate to male members of the family and should abide to their decisions. Moreover, it was evidently clear that the current personal status law was an obstacle to the adoption of a family violence law and kept the questions of custody and marital rape tied to religious regulations and concepts related to relationships between men and women and their reciprocal duties.

Consequently, the family structure and state institutions seek to promote an institutionalized and stereotypical image of women, denying them, in many cases, access to various sectors of the workforce and limits their primary role in the services sector, where they mostly underpaid or unpaid, such as with domestic work. It seems the sectarian, patriarchal, and capitalist structure of this state and its institutions, on one hand, and women's interests, on the other, are moving in opposite directions. Yet, those institutions will continue to provide solutions that act as tranquilizers to maintain the status quo as long as possible.

On the other side, women's organizations have addressed the above-mentioned obstacles in an apologetic manner, with a strong focus on reforms in response to a specific need or problem. In all the years of struggle, the question of the family unit remained untouched and glorified – without reservation in some discourses. Little by little, women's organizations were steered away from engaging with other women, preferring to address the powers that be, who continue to legitimize the sexist structure.

Recently, huge sums were spent on campaigns targeting patriarchal institutions, such as the parliament and religious institutions. This process required tremendous amounts of resources, in terms of efforts, time, and money. Yet the outcome was minimal, in comparison, as the gains achieved throughout this process failed to meet the expectations of those organization and, more importantly, women victims of discrimination and violence.

This shift to addressing institutions and focusing on minor reforms, without tackling the roots of the problem, is highly influenced by the NGOization of the women's movement and the limits of project-based intervention and prevention. This recent phenomenon, which is replicated around the world, pegs the participation of women and other groups calling for gender equality to a limited number of NGO employees who tackle the issue as a career, which necessarily requires a specific type of education, skills, and background. The methods shifted from organizing and enlarging the movement into report-writing and knowledge of international human rights standards and tools, which excludes other means of organizing and delegitimize all struggles outside existing trends and acceptable tools.

Moreover, strategies and interventions by many women's organizations are often shaped and influenced by funding trends, which – in most cases – prefer to maintain the status quo and keep the existing structure of the state untouched. Organizations calling for social change, including women's organizations, are designing their projects according to funding opportunities, which set their priorities and channel the money into specific types of projects.

To challenge the obstacles, women's organizations must ultimately revisit their structures, which hinder mass involvement and obstructs the way of creating a movement able to push for equality and justice. The creation of structures welcoming all women on a peer to peer basis and defending their interests would be a cornerstone in defeating patriarchy and removing the burden of donors. Negotiations and dialogue should take place among different groups of women suffering from patriarchy, classism, and violence, and not be confined to the court of religious and state institutions.

Bibliography:

ABAAD, "We Believe: Campaign to end violence against women," Al-Mustaqbal, 1/1/2012.

ABAAD, "We Believe: Campaign video," YouTube clip, 2/4/2012.

Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi, L’altermondialisme au Liban : un militantisme de passage. Logiques d’engagement et reconfiguration de l’espace militant (de gauche) au Liban, Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne, 2013.

Saada Allaw, "Will KAFA ask 10 MPs to challenge the law?", Assafir, Beirut, 2/4/2014.

Nermine el-Horr, "Souq al-Ijhad al-Sirri (Secret abortion market)," Al-Akhbar, 22/4/2010.

Azza Charara-Baydoun, "Women in Power and Decision-making Positions: Conditions and Restraints," Al-Raida, Issue 126-127, 2009.

Fahmiyeh Charafeddine,” Al-harakat al-nisa’iyya fi Lubnân (Women's Movements in Lebanon)”, ESCWA, 2006.

Bernadette Daou, Les féminismes au Liban. Etude des principales organisations et campagnes féministes (titre provisoire), mémoire de master 2, Université Saint-Joseph, Masters thesis, Forthcoming.

Suad Joseph, “Gender and Citizenship in the Arab World”, Concept, University of California, Davis, 2002.

Carol Kerbaj, "NGOs in Lebanon: Abusing Their Workers in the Name of Human Rights," Al-Akhbar English, 10/7/2012.

KAFA, "Policy Paper on Reforming the 'Sponsorship System' for Migrant Domestic Workers: Towards an Alternative Governance Scheme in Lebanon," January 2012.

KAFA, "So what happened to us would not happen to you," IWD campaign promo featuring the mothers of women victims of violence, YouTube clip, 4/3/2014.

Lara Khattab, Civil society in a sectarian context: the women’s movement in post-war Lebanon, Masters Thesis, Lebanese American University, Beirut, Summer 2010.

Doreen Khoury, "Women's Political Participation in Lebanon," Heinrich Boell Foundation - Middle East, 23/9/2013.

Dana Khraiche, “Dar al-Fatwa rejects draft law protecting women against domestic violence”, Daily Star Beirut, 23/6/2011.

Rajana Hamyeh, "al-Mawt al-Muannath ", Al-Akhbar Newspaper, Beirut, 31/12/2013.

Legal Agenda, "Draft Law on Harassment in the Workplace," Legal Agenda 3 February 2014.

Nisrine Mansour, Governing the Personal: Family Law and Women's Subjectivity and Agency in Post-conflict Lebanon, London school for Economics & political Science, 2011.

Republic of Lebanon, Penal Code, Legislative Decree No.340, 1/3/1943.

Republic of Lebanon, Lebanese Constitution, Promulgated May 23, 1926, with its amendments, 1995.

Seiko Sugita, "Social Care and Women’s Labor Participation in Lebanon," Al-Raida, Issue 128, Winter 2010

UNRISD, "Pourquoi les soins sont importants pour le développement social (Synthèses de l’UNRISD sur les recherches et politiques )," 5 May 2010

Delphine Torres Tailfer, “Women and Economic Power in Lebanon: The legal framework and challenges to women economy,” CRTD-A, 2012.

Ayman Wehbe, "Banat al-Fallahin, Amilat al-Masaneh (Peasant Daughters, Factory Girls)," Al-Manshour, Beirut, 2008.

Najwa Yaacoub and Lara Badre, "Education in Lebanon," Statistics in Focus, Issue 3, April 2012, Central Administration of Statistics, Lebanon.

Nicole Youhanna, "Marriage dissolves Nahr Ibrahim municipality," Al-Joumhouria, Beirut, 13/11/2014.

- 1. Family Violence is is when someone intentionally uses violence, threats, force, or intimidation to control or manipulate a family member. The difference between family and domestic violence is that the first highlights violence committed by an extended family member, while domestic violence covers violence committed by partners who are not necessarily family members or spouses.

- 2. Saada Allaw, "Will Kafa ask 10 MPs to challenge the law?", Assafir, Beirut, 2/4/2014, http://bit.ly/1tpAbX4 (Accessed 7/6/2014).

- 3. UNGA, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), adopted on 18/12/1979, http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/ (Accessed on 26/4/2014).

- 4. Suad Joseph, “Gender and Citizenship in the Arab World”, Concept, University of California, Davis, 2002, http://www.euromedgenderequality.org/image.php?id=487 (Accessed on 6/6/2014).

- 5. Lebanese Penal Code, http://www.madcour.com/LawsDocuments/LDOC-1-634454580357137050.pdf, in Arabic, (Accessed on 2/4/2014).

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. Ibid.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Nermine el-Horr, "Souq al-Ijhad al-Sirri (Secret abortion market)," Al-Akhbar, Issue 1098, 22/4/2010, https://www.al-akhbar.com/node/54031 (Accessed on 2/4/2014).

- 11. Lebanese Penal Code, op. cit.

- 12. Azza Charara-Baydoun, "Women in Power and Decision-making Positions: Conditions and Restraints," Al-Raida, Issue 126-127, 2009, p. 53.

- 13. Seiko Sugita, "Social Care and Women’s Labor Participation in Lebanon," Al-Raida, Issue 128, Winter 2010, p. 31.

- 14. Ibid.

- 15. Ibid.

- 16. UNRISD, "Pourquoi les soins sont importants pour le développement social (Synthèses de l’UNRISD sur les recherches et politiques )," 5 May 2010, http://bit.ly/1nxhflN, (Accessed on 10/7/2014); also quoted in, Delphine Torres Tailfer, “Women and Economic Power in Lebanon: The legal framework and challenges to women’s economy,” CRTD-A, 2012, http://bit.ly/1lIwz3C (Accessed on 12/3/2014).

- 17. Seiko Sugita, “Social Care and Women’s Labor Participation in Lebanon”, Al-Raida, issue 128, October 2010, p. 31, http://bit.ly/1xcvR3C.

- 18. KAFA, "Policy Paper on Reforming the 'Sponsorship System' for Migrant Domestic Workers: Towards an Alternative Governance Scheme in Lebanon," January 2012, http://www.kafa.org.lb/StudiesPublicationPDF/PRpdf47.pdf (Accesed on 2/4/2014).

- 19. Torres Tailfer, “Women and Economic Power in Lebanon: The legal framework and challenges to women economy,” CRTD-A, 2012.

- 20. Ibid.

- 21. Ibid.

- 22. Carol Kerbaj, "NGOs in Lebanon: Abusing Their Workers in the Name of Human Rights," Al-Akhbar English, 10 July 2012 (Accessed on 2/4/2014), http://english.al-akhbar.com/content/ngos-lebanon-abusing-their-workers-name-human-rights.

- 23. Legal Agenda, "Draft Law on Harassment in the Workplace," Legal Agenda 3 February 2014, http://www.legal-agenda.com/newsarticle.php?id=573&lang=ar#.UzwJcVeWn-A (Accessed on 2/4/2014).

- 24. Torres Tailfer, 2012, op.cit.

- 25. Seiko Sugita, 2010, op.cit., p. 31.

- 26. Azza Charara-Baydoun, 2009, op. cit., page 53.

- 27. Nicole Youhanna, "Marriage dissolves Nahr Ibrahim municipality," Al-Joumhouria Newspaper, Beirut, 13/11/2014, http://www.aljoumhouria.com/news/index/103523, (Accessed on 7/9/2014).

- 28. Doreen Khoury, "Women's Political Participation in Lebanon," Heinrich Boell Foundation - Middle East, 23/9/2013, http://www.boell-meo.org/en/2013/09/23/womens-political-participation-lebanon, (Accessed on 6/9/2014).

- 29. Ibid.

- 30. UNDP, "The Millennium Development Goals in Lebanon," http://www.lb.undp.org/content/lebanon/en/home/mdgoverview/overview/mdg3/, (Accessed on 6/9/2014).

- 31. Najwa Yaacoub and Lara Badre, "Education in Lebanon," Statistics in Focus, Issue 3, April 2012, Central Administration of Statistics, Lebanon, http://www.cas.gov.lb/images/PDFs/SIF/CAS_Education_In_Lebanon_SIF3.pdf, (Accessed on 6/9/2014).

- 32. "Masira wataniya wa nashatat wa bayanat wa nadawat fi yawm al-mar'a al-alami (National procession, activities, statments, and workshops on IWD)," Al-Liwaa, Beirut, 11 March 2013, http://www.aliwaa.com/Article.aspx?ArticleId=157313 (Accessed on 30/3/2014).

- 33. For more information on the message of the campaign, please see, KAFA, "So what happened to us would not happen to you," IWD campaign promo featuring the mothers of women victims of violence, YouTube, 4/3/2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XeQiegAewvg (Accessed on 9/9/2014).

- 34. Fahmiyeh Charafeddine, 2006, Al-harakat al-nisa’iyya fi Lubnân (Women's Movements in Lebanon), ESCWA.

- 35. Bernadette Daou, Les féminismes au Liban. Etude des principales organisations et campagnes féministes (titre provisoire), mémoire de master 2, Université Saint-Joseph, Masters thesis, Forthcoming.

- 36. Marie-Noëlle AbiYaghi, 2013, L’altermondialisme au Liban : un militantisme de passage. Logiques d’engagement et reconfiguration de l’espace militant (de gauche) au Liban, Thèse de Doctorat, Université de Paris 1-Panthéon Sorbonne.

- 37. For a list of LCW members, please check the following link: http://bit.ly/1u4ZGPV.

- 38. Lebanese Council for Women (LCW): http://lcw-cfl.org/en/en-us/history.aspx, (Accessed on 28 February 2014).

- 39. Lara Khattab, Civil society in a sectarian context: the women’s movement in post-war Lebanon, Masters Thesis, Lebanese American University, Beirut, Summer 2010, http://bit.ly/1rayoTh.

- 40. Ibid.

- 41. Nisrine Mansour, Governing the Personal: Family Law and Women's Subjectivity and Agency in Post-conflict Lebanon, London school for Economics & political Science, 2011.

- 42. Ibid.

- 43. Rajana Hamyeh, "al-Mawt al-Muannath ", Al-Akhbar, 31/12/2013, http://www.al-akhbar.com/node/197878 (Accessed 11/5/2014).

- 44. Saada Allaw, "Will Kafa ask 10 MPs to challenge the law?" Assafir Newspaper, Beirut, 2/4/2014, http://bit.ly/1tpAbX4 (Accessed 7/6/2014)

- 45. For Kafa’s comments on the amended law: http://www.kafa.org.lb/FOAPDF/FAO-PDF-9-635101053455518206.pdf (Accessed on 2/4/2014).

- 46. Republic of Lebanon, Lebanese Constitution, Article 7: "All Lebanese shall be equal before the law. They shall equally enjoy civil and political rights and shall equally be bound by public obligations and duties without any distinction," 1926, 1995, http://www.presidency.gov.lb/English/LebaneseSystem/Documents/Lebanese%20Constitution.pdf.

- 47. Dana Khraiche, “Dar al-Fatwa rejects draft law protecting women against domestic violence”, Daily Star Beirut, 23/6/2011, http://bit.ly/1rxT1sM (Accessed on 9/9/2014)

- 48. "We Believe: Campaign to end violence against women," Al-Mustaqbal newspaper, 1/1/2012, http://www.almustaqbal.com/v4/Article.aspx?Type=np&Articleid=549237 (Accessed on 9/9/2014).

- 49. ABAAD, "We Believe: Campaign video," YouTube clip, 2/4/2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=trsSvCBLgr0, (Accessed on 9/9/2014).

- 50. "ABAAD concludes international campaign," Lebanon Files, 9/1/2013, http://www.lebanonfiles.com/news/488816 (Accessed on 9/9/2014).

- 51. ABAAD, YouTube campaign video, op. cit.

- 52. Khattab, 2010, op. cit.

- 53. Ayman Wehbe, "Banat al-Fallahin, Amilat al-Masaneh," Al-Manshour, 2008, available at http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=126605 (Accessed 9/9/2014), citing Akram Fouad Khater, Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920, (Berkeley: University of California Press, c2001 2001), http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9d5nb66k/.

- 54. Ibid.

Riwa Salameh is a feminist activist from Lebanon who has been involved in various collectives and NGOs.