Mobilising against the sexual assault and harassment of women

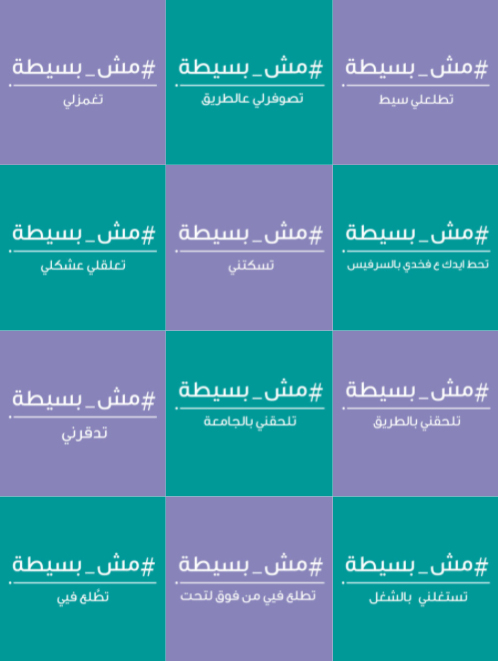

In the absence of legal codes that address women’s sexual assault and harassment in the workplace and the public sphere, Lebanese or non-Lebanese women are discouraged from joining the workforce. These precarious conditions have led to high rates of death for domestic workers due to suicide from repeated abuse; in some cases, workers are murdered by employers. Though victims of harassment in the workplace have the legal right to leave work without notice, this exacerbates women’s situations,as they remain prone to such harassment with no legal protection; they also lose their means for economic and financial sustenance. Aside from Articles 503 and 507 of the Lebanese penal code, which penalise individuals who force others into sexual intercourse or indecent acts outside of wedlock on the condition of presenting witnesses, there are no other references made regarding sexual harassment. This left a huge gap in the Lebanese legal codes – a gap that is reflected in the state’s lack of commitment to protect its citizens from such risks.Civil society organisations, such as Kafa and the Lebanese Council to Resist Violence Against Women, provide care, counselling, and safe shelter to women who experience violence, particularly marital violence, and who have no access to sufficient legal assistance. Initiatives and national campaigns fighting sexual violence and harassment have been on-going over the past decade, almost on a yearly basis. The most recent one is “Mish basita, not okay” which was launched in July 2017 by the Knowledge Is Power (KIP) Project on Gender and Sexuality at the American University of Beirut, in partnership with the Women’s Affairs Ministry.

The Human Rights Watch, Caritas Lebanon, the Migrant Community Centre (established by the Anti-Racism Movement), Amel Association International, Insan, the Danish Refugee Council, and Nasawiya, all provide information about domestic workers’ conditions, chart strategies to end violence against domestic workers, and offer legal assistance in some cases. Nevertheless, the judicial system remains unchanged, and domestic workers are stripped of their documents, making their fate solely dependent on their employers’ will.