On Chaos, Disruption, and Women in Public Space: Cairo’s Street Situation and the Murder of the “Maadi Girl” and the Single “Al Salam Doctor”

In this essay, Nehal Elmeligy uses the chaos, unpredictability, and potential brutality of “the street” in Cairo to reflect on the murder of two Cairene women, the first killed in October 2020 and the second in April 2021.

To cite this paper: Nehal Elmeligy,"On Chaos, Disruption, and Women in Public Space: Cairo’s Street Situation and the Murder of the “Maadi Girl” and the Single “Al Salam Doctor”", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2021-12-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSR.005.006

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/chaos-disruption-and-women-public-space-cairo’s-street-situation-and-murder-“maadi-girl”-andOn a hot summer day in Cairo, some time between the year 2012 and 2015, I did not look both ways before crossing an intersection while I was driving; I was in my early twenties, and still fairly new to driving. As I quickly turned right, an old and sturdy car bumped into my parents’ flimsy Renault, putting me in a state of shock and leaving the driver understandably in rage. I called my mom for help, who in turn called my uncle Ehab, who was known for his street wits and diplomatic skills. He quickly came to my rescue, and in an attempt to get me out of paying compensation for the older man whose car I damaged, he explained: “This is a street, man, there is no telling whose fault it is.” Referring to the chaos of Cairo traffic, of “the street” with its pedestrians, bicycles, vegetable stalls, and lack of stop signs or traffic lights, my uncle was essentially saying it could have been anyone’s fault because accidents like these happen; it’s a street, after all. To my surprise, his argument resonated with the older man and bystanders alike; I was free to go.

In this essay, I use the chaos, unpredictability, and potential brutality of “the street” in Cairo to reflect on the murder of two Cairene women, the first killed in October 2020 and the second in April 2021. Even though these women did not die in car accidents, I view the street’s chaos as an overflowing state of being that seeps into and represents social life in public space. To offer a larger picture of Cairo’s traffic and “the street” beyond my accident, I use the description of economist and urban planner David Sims (2010), which captures Cairo’s bewildering and overwhelming chaos:

[I]t is hard to find a description of Cairo, however short, which does not manage to conjure up images of near-Armageddon when it comes to traffic, and to many a casual visitor the ensnarled streets rank only second to the Pyramids of Giza as the defining impression of the city. Visitors are shocked by the erratic and seemingly suicidal driving, by the nonchalance of the meandering pedestrians, and by the seemingly perverse disregard for traffic rules. (227)

Sims draws an image of public space where everything is happening, and anything can happen. For visitors, this scene is shocking, unpredictable, and seemingly illogical. To a native Cairene, Cairo traffic is not shocking, but it is always unpredictable, and it claims people’s lives every day. The chaos of the Cairene street does not only manifest in traffic; it also manifests in women’s everyday experiences in Cairo’s public space, of which the street is both a part and a symbol.

This essay examines two spaces within Cairo’s public space: the street and the apartment, specifically that of a single woman living alone. The street is a public space because it is accessible to anyone, and has no gates or borders; what occurs on the street is visible to everyone. While an apartment has walls, windows, and a door, a young single woman living alone defies the rules of sexual respectability and social propriety, and therefore this woman is always under scrutiny, and is being watched by her neighbors, doormen, landlords, and nearby shopkeepers. Being unmarried and living alone, especially as a young woman, means she is in “danger” of having sex outside of marriage, which would bring shame and scandal onto herself, the building in which she resides, and possibly the street where the building is located.

The first murder case is of “The Maadi Girl,” a woman walking home from work at night; and the second is of the “Al Salam Doctor,” a woman living alone, receiving a male guest. They were both murdered, I argue, partly due to the unpredictability and fatal brutality that comes from the chaos of the Cairo street or the Street Situation/Wad’ el Share’. I will elaborate on this concept after I briefly sketch the events of the two murder cases.

The Maadi Girl

On Wednesday October 14, 2020, almost every Egyptian person I know on Facebook was commenting on or sharing a post or article about the same incident: a 25-year-old Egyptian woman, Mariam Mohamed, was walking in the evening in Maadi (supposedly one of the safest neighborhoods in Cairo) – some sources report that she was returning home from work – when two men – some sources say three – in a vehicle verbally harassed her (Osman 2020). When she talked back, they tried to steal her handbag. It’s unclear what happened next, but somehow, Mariam held onto her bag even as the men pulled it into the car (Egyptian Streets 2020a; BBC Arabic 2020). The two harassers kept on driving, dragging her along for a few kilometers to her death. Two of the men were arrested and sentenced to the death penalty, and the third was acquitted (Abdelhamid 2020; Egypt Independent 2020). I have read multiple reports and articles in English and Arabic about this murder; some say that there were three, not two, men, and that they weren’t harassing her: they were “only” trying to steal her bag, which is what was reported a few weeks after the murder (Egyptian Streets 2020b). Even if it’s true that they weren’t harassing her, harassment and women’s freedom of movement in Egyptian cities, and what/how some men think about and perceive them took center stage in Egyptian social media and news.

The Al Salam Doctor

On Tuesday March 9, 2021, a 34-year-old woman doctor, whose identity has not been revealed to this date, received a male a guest in her apartment, where she lives alone in Al Salam District in Cairo (Egyptian Streets 2021). The doorman reported this to the (male) landlord. Following that, a male neighbor/resident from the building and the landlord’s wife broke into the woman’s apartment and physically assaulted her, leading her to fall off her balcony on the 6th floor to her death at the foot of the building. Her body, however, was found outside another building in the same neighborhood (Dabsh and Kara’a 2021; Egyptian Streets 2021; Osman, 2021). Reports claim that she was either pushed to her death or fell during the attack (Burke 2021). The three men were arrested, but until now, they have not been charged (Dabsh and Kara’a, 2021). The landlord has denied the murder charges, claiming the woman committed suicide because she was going through a “psychological crisis” (Dabsh and Kara’a 2021; Egyptian Streets 2021). This story, like Mariam’s, was met with public outrage on social media, and the National Women Council’s (NCW) President, Maya Morsy, denounced the crime on Facebook saying that the NCW “rejects all forms of violence and thuggery” (Egyptian Streets 2021).

I return now to the lens through which I see these two murder cases, the Street Situation/ wad’ el share’. In his book, Disruptive Situations: Fractal Orientalism and Queer Strategies in Beirut (2020), Ghassan Moussawi uses the Arabic word الوضع /al-wad’ (the situation) as both a description and an analytical tool to understand what happens when everyday life disruptions and violence become the norm in city life. He explains that al-wad’:

[I]s a general and nebulous term, commonly used in post-civil war Lebanon to refer to the shifting conditions of instability in the country that constantly shape everyday life. It simply refers to the ways that things are, the normative ordering of things and events. However, it produces feelings of constant unease, anticipation of the unknown or what the future might bring, and daily anxieties. (5)

I use al-wad’ as an analytical lens through which I highlight “the situation in the street/the street situation,” or وضع الشارع /wad’ el share’, for women Egypt – whether in Cairo or other urban settings – as one that is unpredictable and anxiety-inducing. As Moussawi (2020) explains, al-wad’, wad’ el share’ in Cairo is also “always disruptive […] it occurs when the out of the ordinary becomes the normal” (6). The Cairene street with its near-Armageddon traffic, which I use as a building block of the concept of wad’ el share’, is indeed disruptive to people’s daily life, errands, mental health, patience, and peace of mind; it is out of the ordinary, but has become the norm.

I employ “the street” to signify public space in general, which includes the street itself. Wad’ el share’ encompasses the chaotic and potentially deadly daily and around-the-corner occurrences for women in Cairo’s public space. In the ongoing wad’ el share’, women who appear to be defying patriarchal societal norms or appropriate ways of being and appearing in public space are continuously policed, disciplined, or reprimanded by strangers and onlookers who are mostly men. Within wad’ el share’, all women, it seems, enter what resembles a parasocial interaction or relationship with the public, where onlookers give themselves the right to watch, look, judge, and interfere in a woman’s life because she is publicly not abiding by normative social traditions through the way she is dressing, behaving, or living.

Wad’ el share’ in Cairo is disruption incarnate. Having to face it every day, many Cairene women resort to strategies, or “practices of negotiating,” to survive (Moussawi 2020, 6). Moussawi writes that al-wad’ “is a way of describing queer times,” and the ways that some people are consequently forced to use “queer tactics or strategies” to survive “under such disruptive conditions.” These “queer tactics,” according to Moussawi, “gesture toward an expansive understanding of queerness – one that does not necessarily link to LGBT identities but to practices of negotiating everyday life” (2020, 6). What might be “normal” for some is, quite literally, a queered existence for others.

The Maadi Girl and Wad’ el Share’

On the street, there is always a chance that a man would grab a woman’s breasts, slap her buttocks, pull her hair, say vulgar things to her, or worse. Mariam being killed because she was walking home is out of the ordinary to say the least; but sadly, her murder a result of being a woman in the streets of Cairo is slowly becoming part of what is considered “normal.”

The following queer tactics are just a few examples of how Cairene women, myself included, consistently negotiate our everyday existence within wad’ el share’. It starts before leaving the house: am I walking or taking a taxi? Taking the metro or driving? My decision determines what I wear, what time I can leave the house, and what time I can return home. Are my headphones ready? Once I’m on the street, I have to stay alert: “khaly ‘eineky fe wust rasek/keep your eyes in the middle of your head,” I tell myself.[1] Is there a sidewalk I can walk on? Are there men on the sidewalk? Are there men sitting at the ‘ahwa (café)? Do I have time to take the longer route to avoid them? How many men are loitering by the corner kiosk today? Damn, the streetlights here are off, let me turn around. There are men in the car next to me; I should turn the music down if we both stop at the traffic light so they won’t stare or make any comments. Wad’ el share’ disrupts our emotions, morale, daily flow, mobility, trust in men, future plans, and peace of mind. Even worse, wad’ el share’ can end our lives.

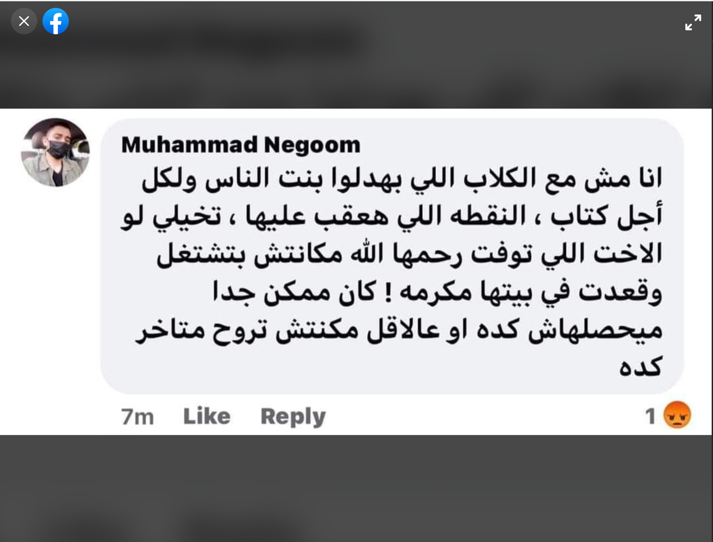

Many Egyptians, however, trivialize wad’ el share’ and how it harms women, and focus on what the women were doing or wearing to blame them for the harm that befalls them. A sample of this perspective is shown through Facebook posts written by two different men about Miriam, which were widely circulated. In the first one (Figure 1), which was shared 1,800 times, Youssef Helal[2] said: “Hijab, tight pants, and make up; it’s only natural that this happened to her, young men can’t take it anymore.” In the second, which was shared 2,300 times, Muhammed Negoom[3] said:

I’m not with the dogs who screwed over the decent girl […] But the point I’m going to comment on: imagine the sister who died, may God have mercy on her, did not work and stayed dignified at home! This may not have happened, or at least she should not have walked home so late.

Both men justify wad’ el share’, and Mariam’s murder, in different ways. In the first post, Helal finds Mariam’s clothes and makeup provocative, even though she is wearing a hijab. His argument follows this logic: a young man has pent up sexual desires; a young man sees a “provocative” woman; this young man kills this young “provocative” woman; this young woman deserves it, because she was “provoking” the young man. What would he have said if she wasn’t wearing the hijab?! Negoom, in the second post, questions why any woman would have left the household to begin with. Why did she have to work? Women maintain their dignity by staying home, apparently. If she did have to leave the house, why did she have to be on the street so late? The narrative of victim-blaming remains intact no matter what.

In my experience as a native Cairene and as a researcher of women’s experiences and resistances in public space in Cairo, (many) Egyptian men consider public space to be their “universe” (Mernissi 2003, 138). Some men consider women’s mere appearance in public spaces, or an appearance that is “too conspicuous, daring or inappropriate” – as a result of being loud, wearing revealing clothes or bright colors, smoking a cigarette, being out late or after dark, or even being too tall – as an encroachment of their territory. This translates into the severe limitation of women’s freedom, mobility, and ability to appear in public as they wish, and puts them in potential psychological and physical danger. In some neighborhoods in Cairo, a woman without a hijab or who is not dressed conservatively will stand out, which may “provoke” both men and women to not only harass her, but to comment on her clothes or morality. Interestingly, women like Mariam, who wear the hijab, still experience verbal and physical harassment. This leads me to agree with some of the sources that reported that the harassers ended up killing Mariam because she “talked back,” not because of her presumably provocative makeup and tight pants (Egyptian Streets 2020; Osman 2020).

Black feminist scholar bell hooks (1989) writes that as a child and woman growing up and living in a southern, Black, male-dominated community, “back talk” and “talking back” to men was a courageous act of “speaking as an equal to an authority figure […] daring to disagree [or] just having an opinion. To speak then when one was not spoken to was […] an act of risk and daring” (5). For hooks, talking back signals the shift of “the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and struggle side by side” from an object to a subject (hooks, 1989, 9). In other words, hooks perceives “talking back” to authority as a refusal of domination, or a challenge to the oppressor. This is exactly what Mariam did: talking back to her harassers was a daring act and a risk. It turned her from a perceived object of harassment to a resistant and vocal subject, at the cost of her life. I also see Mariam’s back talk as directed to the chaos and unpredictability of wad’ el share’. The chaos of the Cairene street flows between its cars, buses, Tuk Tuks, microbuses, and bicycles, and spills between the people in the street and their relationships. Perhaps, Mariam’s back talk was both an expression of resistance and frustration at the normative state of the Cairene street, where everything happens, and anything can happen. It was a reaction and vocal denouncement of the disruption of the mundane activity of her returning from work. Mariam was most likely not new to it, but that does not mean she had made peace with it as a fact of public social life.

The Al Salam Doctor and Wad’ el Share’

Al Salam Doctor – and all women who live alone in Cairo, especially in working class neighborhoods where their social class might not protect them – “talk back” to patriarchy instead of “bargaining” with it (Kandiyoti 1988). hooks identifies “talking back” as an act of feminist resistance that is confrontational and rebellious. Therefore, “talking back” can serve as a symbol for all conspicuous acts by women that defy patriarchal authority. As we have seen with Mariam, patriarchal authority is bound with wad’ el share’; by living alone as a single woman, the Doctor talked back to wad’ el share’. Moussawi (2020) explains that al-wad’ is constantly changing; it has no clear beginning or end ( 6). Somewhat similarly, wad’ el share’ is not geographically-bound (like the street). It exists in, and encompasses, all public space, and materializes or goes into effect when a woman “talks back” to it, when her very presence and defiance become too conspicuous.

According to Egyptian law, it is legal for women to rent or own apartments, live alone, or host men to whom they are not related. The Doctor was not violating Egyptian law; she was violating the normative, gendered, societal morality code. To preserve a woman’s sexual purity, which is synonymous with her honor and her family’s, most women in Egypt, regardless of religion and class, must only have sex within the institution of marriage. Living alone is an act that raises suspicion of a woman’s sexual activity, and the subsequent tainting of her honor and smearing of her family’s and neighborhood’s reputation. While women are responsible for carrying the burden of this honor, men are the ones responsible for protecting it by controlling their female kin (mostly within their immediate family), to the extent that they sometimes kill them due to “real or perceived sexual misconduct” in a crime dubbed “honor killing” (Moghadam 2003, 122-123). The law is, in fact, complicit in this instance: judges in Egypt may decrease the sentence if a case is proven to be honor-related (Khafagy 2005). Almost all coverage of the murder of the Doctor called it an honor killing, though of a different nature (Osman 2021): it is uncommon, or at least not widely known, for cases where men kill (or cause the death of) women to whom they are not related for “sexual misconduct.” This makes the Doctor’s case emblematic of wad’ el share’.

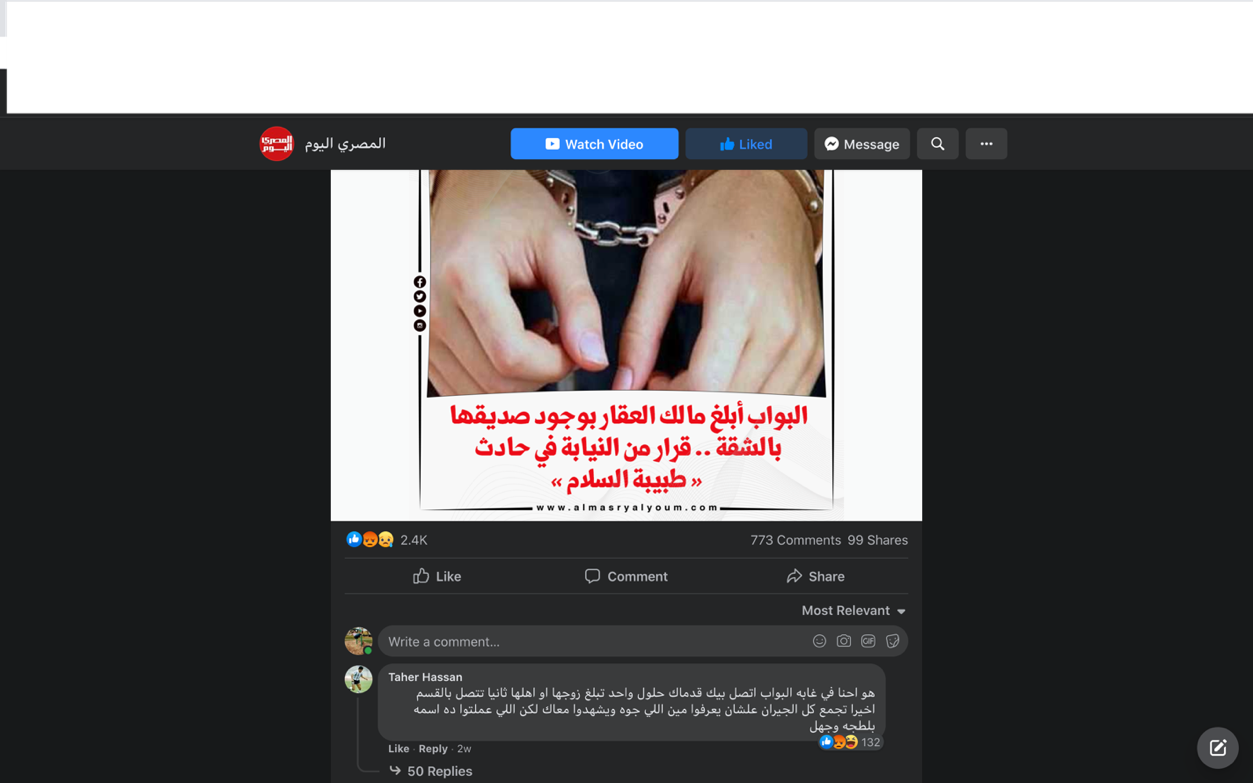

How chaotic, how unexpected, how disruptive to have your door kicked down by fellow citizens, to whom you are not related, meaning to cause you harm because they disapprove of and are offended by something you are doing in your own home.[4] Maya Morsy, the NCW president, and Taher Hassan[5], one of the men commenting on the story on the Facebook page of Al Masry Al Youm newspaper, hit the nail on the head when they described what happened as thuggery or baltagga/ بلطجة. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, thuggery means “violent behavior, especially of a criminal nature.” In Arabic baltagga/ بلطجة means “a state of chaos, vandalism and lawlessness/acting outside the law” (Almaany.com).[6] As the Arabic definition shows, and to my knowledge as an Egyptian, baltagga can be, but does not have to be, violent. So even if the perpetrators had only knocked on the Doctor’s door and asked her guest to leave, this is baltagga. Baltagga is enacted by people who take matters into their own hands and appoint themselves as the persons in charge. Their baltagga is as much a creator of chaos as it is a result or a byproduct of it. Baltagga, therefore, operates within and is an integral component of wad’ el share’. Within wad’ el share’, everything happens, and anything can happen at any time. Its chaos enables patriarchal guardians, who already have socially-backed power, to assume authority over women’s lives and actions. It enables a kind of baltagga that is not bound to street gangs and fights, but that polices women and could suddenly punish them in line with the logics of wad’ el share’.

I don’t know how or why the Doctor came to live alone, and whether her family was supportive of that decision. What I do know from my own experience is that just as women use queer tactics to negotiate their presence in the street, most single women who want to live alone, or live separately from their parents, use queer tactics to negotiate patriarchal gate-keeping of who gets to live alone, and under what conditions. I learned from a Cairene woman I interviewed in 2017, that some women looking to rent an apartment alone use a code word with real estate brokers: freedoms apartment.[7] These women pay a premium to live in an apartment where the doorman, the neighbors, and the landlord will not interfere in their business. Essentially, these patriarchal guardians perform another form of baltagga by exploiting these women’s desires to live alone, and requesting a bribe to turn a blind eye to what they perceive to be a non-normative and conspicuous living situation. Another woman recounted to me several instances when she did not face a lot of difficulty renting an apartment in Cairo because she is not from Cairo, and so it was understood why she wasn’t living with her family. However, the doorman or landlord would tell her about a curfew by which she must abide, and that she cannot have men visit her. As this and the Doctor’s case show us, securing a place to live alone does not guarantee that the women will be left to live as they wish. Their lives are not a private matter; they are as public as the façade of the apartment in which they live.

This is a different kind of obituary – an analytical one. I mourn Mariam and the Doctor. I mourn their lost and robbed lives. I also mourn our, (some) Egyptian women’s, robbed/constrained/challenged freedom of mobility, of being and living as we wish, of being conspicuous in public space. I mourn the status quo of public space. I ponder the possibility of wad’ el share’ not being the state of Cairene public space, of chaos not being its main descriptor and persevering characteristic. I don’t know. I was born and raised in Cairo, and the city has only gotten bigger, more crowded, and more chaotic; the chaos has become more widespread and a part of its essence. With that said, in my experience, and through my research, I know Egyptian women are becoming more defiant in their occupation of public space. This essay is centred on Mariam’s and the Doctor’s murders, but it is also about why they were murdered – because they took up space that was not meant for them and appeared/lived in ways that were not approved for them. Existing within and trying to maneuver wad’ el share’ consistently disrupts, halts, and derails the lives and routines of Egyptian women. But Mariam and the Doctor, as well as others who behave and live like them, remind and show us that Egyptian women disrupt wad’ el share’ as much as it disrupts them.

References

Abdelhamid, Ashraf. 2020. “Egypt: The Death Sentence to the Murderers who run over and Dragged the Maadi Girl.” Alarabiya Arabic, November 25, 2020. https://www.alarabiya.net/ar/arab-and-world/egypt/2020/11/25/%D9%85%D8%B...

AlMaany.com. n.d. https://www.almaany.com/ar/dict/arar/%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%AC%D8%A9/

BBC Arabic. 2020.“The Maadi Girl: Mariam’s murder shocks the public and provokes questions regarding women’s safety in Egypt.” October 15, 2020. Accessed February 15, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/arabic/trending-54556907

Burke, David. “Three Men Arrested as Doctor Falls to her Death in Suspected Honour Killing.” Mirror, March 24, 2021. https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/three-men-arrested-doctor-falls-23785175

Dabsh, Hamdi and Ibrahim Kara’a. 2021. “Details of Al Salam Doctor’s Death: ‘the defendants broke down her apartment’s door and accused her of practicing vice (having sex).’” Al Masry Al Youm, March 13, 2021. https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/2281314

Kandiyoti, Deniz. 1988. “Bargaining with Patriarchy.” Gender and Society 2(3): 274-290.

Egypt Independent. 2020. “Cairo Court Sentences Killers of Maadi Woman to Death.” December 30, 2020. https://egyptindependent.com/cairo-court-sentences-killers-of-maadi-woman-to-death/#:~:text=In%20its%20final%20verdict%20the,One%20other%20defendant%20was%20acquitted.

Egyptian Streets a. 2020. “Egyptian Woman Killed after being Dragged by Car.” Egyptian Streets, October 14, 2020. https://egyptianstreets.com/2020/10/14/egyptian-woman-killed-after-being...

Egyptian Streets b. 2020. “Two Sentenced to Death for Killing 24-year-old Maryam in Egypt’s Maadi.” Egyptian Streets, November 26, 2020. https://egyptianstreets.com/2020/11/26/two-sentenced-to-death-for-killin...

Egyptian Streets. 2021. “NCW Condemns the Murder of an Egyptian Woman at the Hands of her Landlord over Male Visitor.” March 13, 2021. https://egyptianstreets.com/2021/03/13/ncw-condemns-the-murder-of-an-egy... hooks, bell. 1989. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. New York: Routledge.

Khafagy, Fatma. 2005. Violence against Women: Good practices in combating and eliminating violence against women: Honour killing in Egypt. UN Division for the Advancement of Women, Vienna, Austria.

Mernissi, Fatima. 2003. Beyond the Veil: Male-female Dynamics in Muslim Society. London: Saqi Books.

Moussawi, Ghassan. 2020. Disruptive Situations: Fractal Orientalism and Queer Strategies in Beirut. Pittsburgh: Temple University Press.

Osman, Nadda. 2020. “Outcry over Egyptian Woman Harassed and Run Over by a Group of Men.” Middle East Eye, October 15, 2020. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/egypt-woman-killed-harassed-triggers-outcry

[1] خلي عينيكي في وسط راسك

[2] Image 1 in the Appendix

[3] Image 2 in the Appendix

[4] Under oppressive regimes, state actors do knock down citizens’ doors and arrest them unexpectedly. But the men and women implicated here are not state actors, making the case more jarring.

[5] Image 3 in the Appendix.

[6] حالة من الفوضى والتّخريب والخروج عن القانون

[7] شقة حريات

Nehal Elmeligy is a PhD student at the Department of Sociology minoring in Gender and Women’s Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA. She earned her MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. Her publication, based on her MA research, entitled Making a Scene: Young Women’s Feminist Social Nonmovement in Cairo is published in the Journal of Resistance Studies. You will also find a future publication of hers in Gender and Society in February 2022 entitled Airing Egypt’s Dirty Laundry: BuSSy’s Storytelling as Feminist Social Change. In her dissertation fieldwork in Egypt in 2022, she plans conduct qualitative research to investigate the developing feminist counterpublic on social media, and its connections to material, everyday life.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ElmeligyNehal

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nehal.elmeligy