Conflict Analysis bulletin, Issue 1, November 2015

Issue 1, November 2015 - العدد رقم ١، تشرين الثاني ٢٠١٥

About the bulletin

The Conflict Analysis bulletin, part of the Conflict Mapping & Analysis project (CMA) is an initiative by Lebanon Support, with the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), available on the Civil Society Knowledge Centre (CSKC), Lebanon Support’s knowledge platform. It aims to make available and accessible information and research about conflicts in Lebanon, in order to better understand their underlying causes, and inform interventions and policy-making.

This bulletin highlights a selection of the latest publications on the CMA’s page, including papers, articles, reports, visuals, and interactive content. Additionally, the bulletin includes

visualisations of main conflict trends during the last quarter.

Defining Conflict:Going beyond the view of conflict through a security framework associated with belligerency and violence, Lebanon Support upholds that conflict is of a socio-political nature. It thus sheds light on dynamics underlying a broad spectrum of violent and non violent contentions including social movements, passing by conflicts opposing minorities (ethnic, religious or sexual among others) as well as local, national or regional actors’ policies. Read more and check the interactive conflict map here.

1. Overview of conflict classifications between July 2015 and October 2015

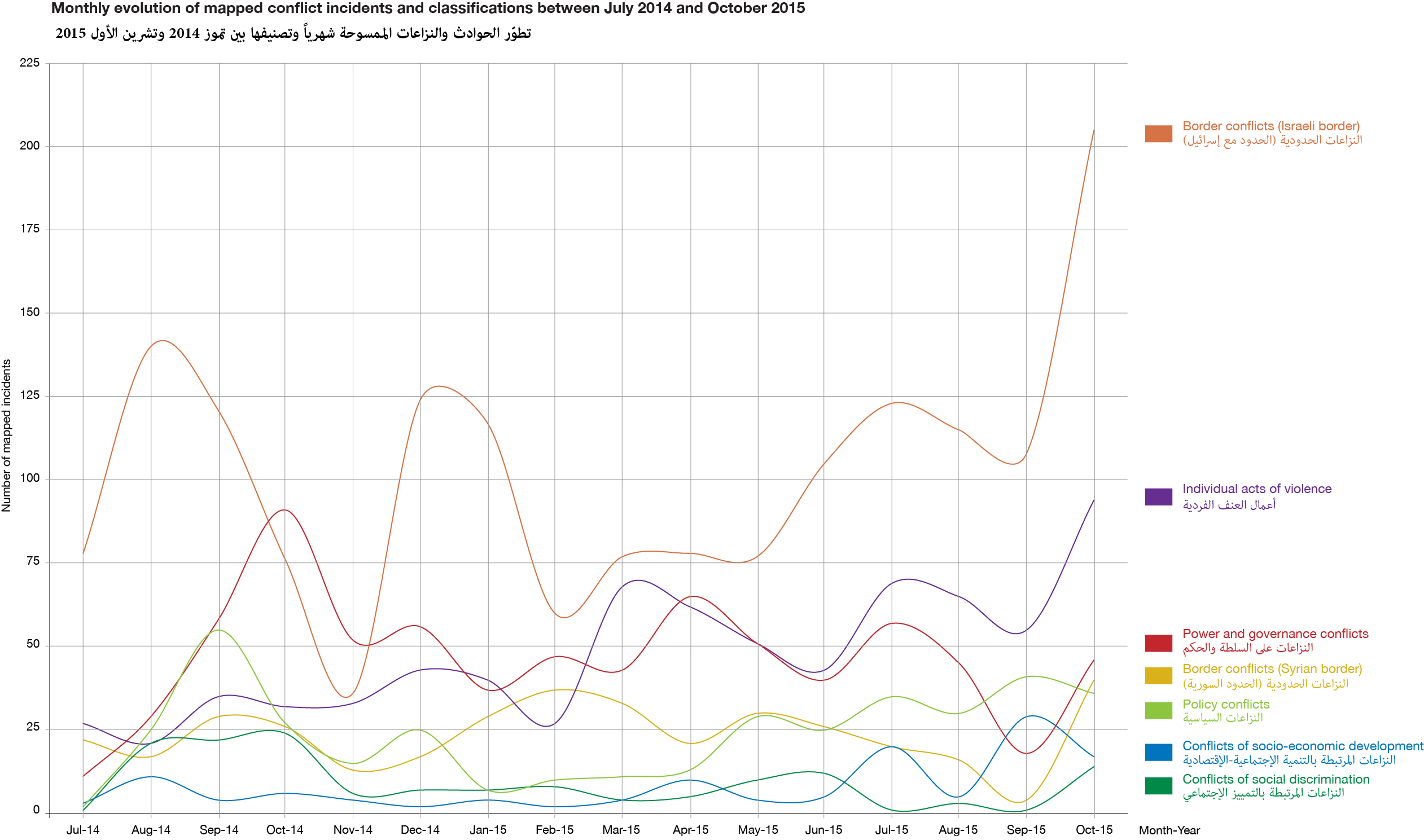

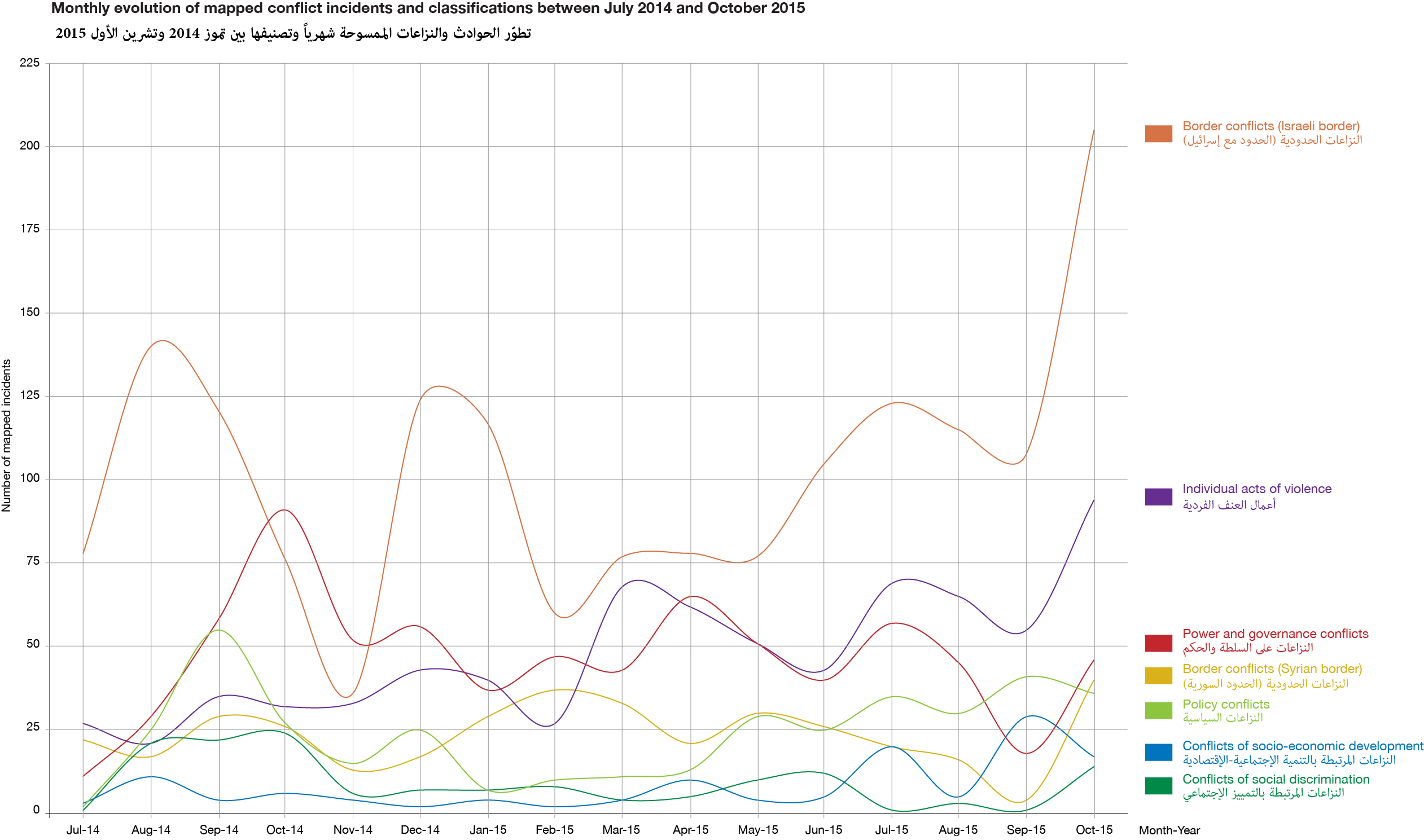

The above graph demonstrates the fluctuations of mapped conflict incidents between July 2014 and October 2015.

The vast majority of Israeli border violations are Israeli overflights violating Lebanese airspace. These are generally routine reconnaissance flights in violation of UN resolution 1701. However, there are also cases of Lebanese airspace being used for jets to launch missiles at targets inside Syria.

The Summer of 2015 saw spikes in conflicts of socio-economic development and policy conflicts. Many of these incidents were due to an influx of collective action movements which included strikes, sit-ins, and protests surrounding state policy and labour issues. Policy conflicts increased from July to October due to the waste management conflict, though these protests developed into a wider set of political grievances against the Lebanese government (see section 2 below). These policy conflicts are primarily located in Beirut due to it being Lebanon’s capital and the seat of government.

Cases of Syrian border violence, involving clashes between LAF and Hezbollah forces with militant groups from Syria noticeably dropped during the late summer of 2015.However, the month of October has seen a resurgence in violent incidents in Arsal such as bombings, suggesting a break from this trend. Furthermore, it is important to note that the majority of all power and governance conflicts occurred in Tripoli, Arsal and the wider Baalbek area, often involving militants from Syria. The Ras Baalbek timeline peaked from late January to late February 2015 with a total of 24 incidents from January 23rd to February 28th. Notably, 4 of these incidents occurred on January 23rd, 7 on February 25th and 8 on February 26th 2015. These three days in which the LAF mainly clashed with militants in Ras Baalbek accounted for over two thirds of the mapped incidents in the aforementioned time frame. Though the clashes are still ongoing, there has been a relative drop in violence, with only 3 incidents of clashes in Ras Baalbek in October. The Arsal timeline is on-going and rather consistent throughout time, though the number of incidents began to slightly decline in July 2015. Tripoli's timeline is also on-going though there has been a decline in incidents since June 2015. While there were 14 incidents mapped in May 2015, June only revealed 8 incidents, with violence dropping to an all time low in August, with only 3 incidents.Taken together, these categories show an enduringly high level of incidents occurring as spillover from the Syrian conflict. In the case of Arsal and Ras Baalbek (links lead to Spot On Events with interactive timelines and contextual articles), militant activity appears to be mainly due to militants retreating from conflict in Syria and being pushed into Lebanon, rather than deliberate ISIS or Nusra front strategy to attack Lebanon.

Furthermore, the security situation in the Palestinian refugee camp of Ain el-Helweh (link leads to Spot On Event on Ain el-Helwe) has deteriorated in recent months. It is important to highlight that tensions in the Ein el-Helweh camp have been ongoing at least in the last year, as shown in the interactive map and timeline. The violence has contributed to counts of Individual acts of violence and power and governance conflicts (for definitions of these categories follow this link). This is partly attributable to Palestinian refugees arriving in the camp from Syria which has contributed to the worsening of the socio-economic situation. The arrival of Palestinian refugees from Syria has reportedly contributed to exacerbate tensions, as shown in this report on Saida, although statistical data is still not available. As highlighted in a recent paper published by Lebanon Support, radicalisation trends in the camp are concomitant with ongoing mediation processes with the attempts to create and maintain a Joint Security Force in collaboration with the Lebanese Army. Moreover, the power and governance conflicts have primarily been between Fatah, as a security force,and Salafist groups, such as Jund al-Sham. Overall, there have been 18 number of individual acts of violence (incidents that do not have a specifically known political agenda) during the last quarter, with a total of 28 incidents since the beginning of the mapping exercise in June 2014. Since the beginning of our conflict mapping analysis, there have been 27 incidents coded in Ain el-Helweh, all mapped as power and governance conflicts. 15 of those incidents occurred during the last quarter, indicating a spike in violence in these months. 7 of these incidents were of hand grenades tossed by unknown individuals within the camp while 6 incidents included violence from militant groups identified as as Jund al-Sham and ISIS.These incidents appear to be occurring due to the deteriorating security situation in the camp and the struggles of day-to-day life for refugees.

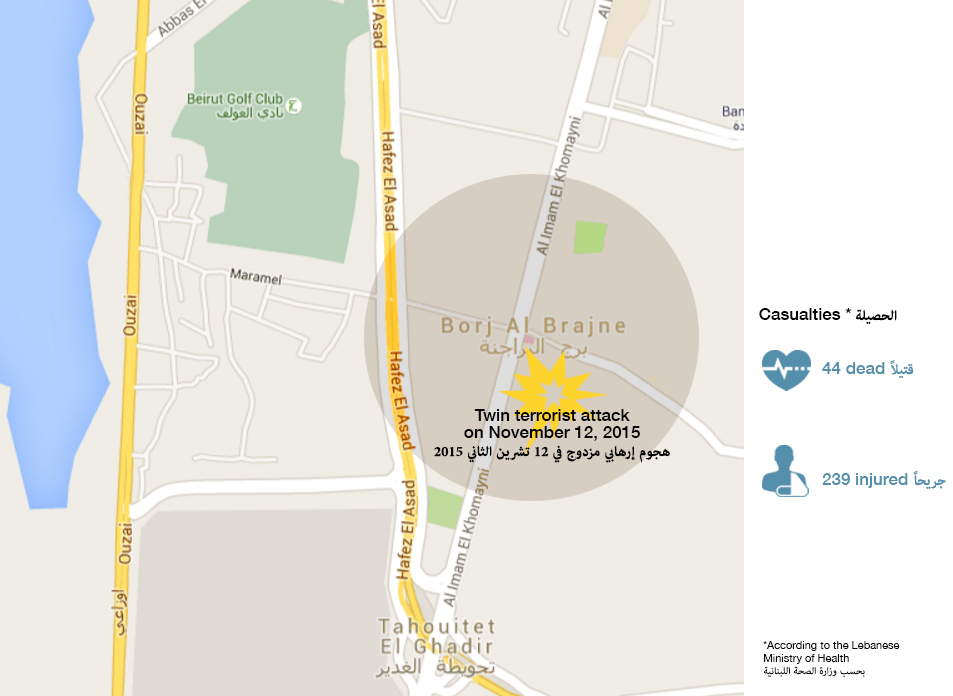

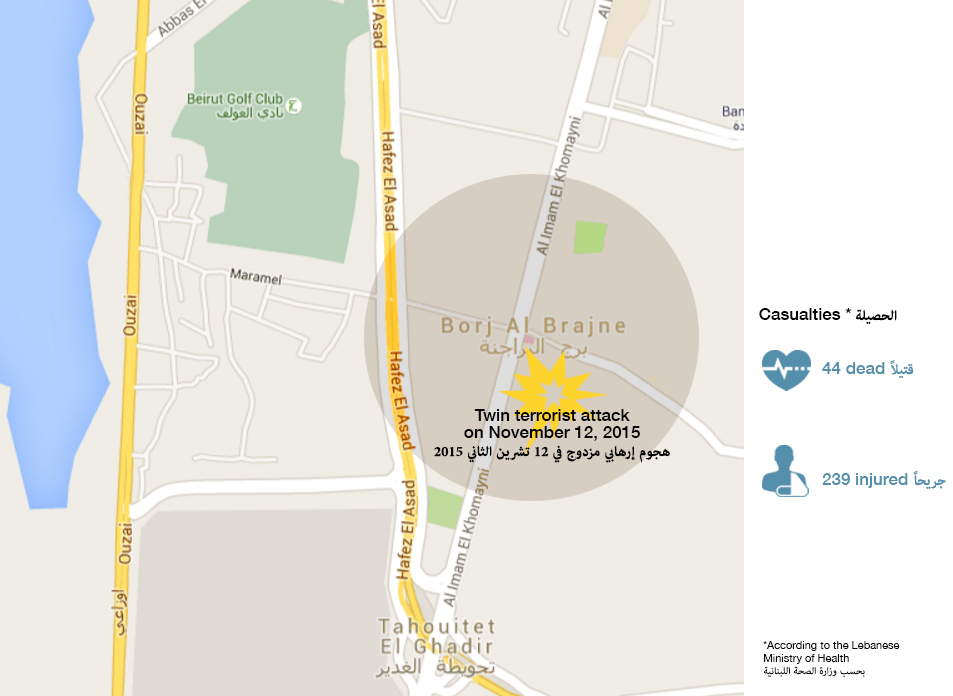

Attack on Borj al-Barajneh

On November 12th, twin bombings were carried out by suicide bombers in the populous suburb of Borj al-Barajneh, located in Southern Beirut. The area is politically affiliated with Hezbollah and homes the Palestinian refugee camp of Borj al-Barajneh. It is equally important to note that the suburb is a popular commercial and residential area located off a major highway leading to the Beirut Rafic Hariri International Airport. Immediately after the explosions, the Islamic State published a statement claiming responsibility for the attack, stating that bombings were meant to target Shia “heretics” and Hezbollah supporters. Notably, the bombings coincided with the last day of the holy month of Muharram for Shias.

The explosions came during rush hour as people were finishing prayer at a nearby mosque. The first suicide bomber detonated 7 kilos of explosives in the midst of a crowd near a bakery while on his motorbike. Minutes later, as people rushed to the scene to see what happened, a second suicide bomber detonated 2 kilos of explosives approximately 50 meters away.

A government source noted that the second suicide bomber was headed towards Al-Hussein Mosque but was tackled by Adel Termos, a local of Borj al-Barajneh, when he detonated. While Termos did not survive the bombing, he reportedly saved dozens who were in the mosque at the time. The body of a 3rd suicide bomber whose explosives failed to detonate was also found at the scene of the attack.

Double bombings are an increasingly common tactic, as was seen in Tripoli in January. After one bomb detonates, another bomber exploits the situation by either waiting to detonate at a narrow escape point as people flee, or moving into a crowd that forms to help people hit by the first. Being mobile, the bomber is able to position themselves, given the reaction of the crowd to maximise the impact of the second blast.

The Ministry of Health has numbered casualties at 44 while over 230 were injured by the bombing, many left in critical condition. The explosions also caused great infrastructural damage, one witness recollecting that people were being “killed by glass and bricks falling on them.”

In response to the bombings, Prime Minister Tamam Salam declared the day after the bombings a national day of mourning while the Ministry of Education declared that all schools and universities will be closed as part of this mourning. The Ministry of Health also declared that all medical treatment of those injured in the bombings would be paid by the state.

Hezbollah top aide Hussein Khalil stated from the explosions site, “What happened here is a crime…This battle against terrorists will continue as it is a long war between us.” Addressing the bombing a day later, Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah stated that the attacks strengthened Hezbollah’s determination in its fight against the Islamic State (IS) in Syria while urging his supporters not to retaliate against Syrian refugees for IS’s atrocities.

Within 48 hours of the bombing, Interior Minister Nuhad Mashnouq announced that a terrorist network of 9 individuals were arrested in connection to the bombings. 7 of the suspects were of Syrian nationality while 2 were Lebanese nationals. Mashnouq went on to describe one Lebanese detainee, Ibrahim Jamal, as a would-be suicide bomber arrested in Tripoli when his explosive belt did not detonate. The Tripoli native told investigators that he was part of an ISIS cell that dispatched from Syria into Lebanon just 2 days before carrying out the bombings, though investigators have not verified this to date. The second Lebanese detainee, identified as A.S, helped smuggle 2 suicide bombers from Syria into Arsal. According to the National News Agency, upon raiding the trafficker’s house in Labweh, Bekaa, security forces seized counterfeit documents and a vehicle suspected of transporting the terrorists.

2 of the 7 Syrians arrested were described as supposed-to-be suicide bombers in the attack but did not assist in the bombings due to a change of plans.

On November 15th, General Security also arrested Ibrahim Ahmad Rayed, a Lebanese man, and Mustafa Ahmad Jaref, a Syrian, for funding and planning the Borj al-Barajneh bombings, though it is not clear whether these two arrests are included in Mashnouq’s 9 announced arrests.

Mashnouq further revealed that the smuggled bombers took refuge in the Borj al-Barajneh refugee camp and a flat in Ashrafieh where they assembled their explosive belts before carrying out the attacks. 5 suicide bombers were originally planning to enter Rassoul al-Aazam Hospital in Borj al-Barajneh but backed down from their plan due to heavy security surrounding the hospital.

While the incident and supposed infiltration of ISIS into Beirut has come as a shock to many, it is important to note that the Lebanese Armed Forces are constantly involved in clashes within the Bekaa Governorate, more specifically, in Ras Baalbek, Baalbek and Arsal. The steady presence of violence within Tripoli over the past few years due to the Syrian conflict has also been thought to breed jihadi sympathisers, allowing for the radicalisation of nationals, such as the Lebanese accomplices in custody. Notably, on the same day of the Borj al-Barajneh bombings, a 10 kg explosive device was found and dismantled by the Lebanese Armed Forces in Tripoli.

2. Conflict Trend: Focus on Collective Actions

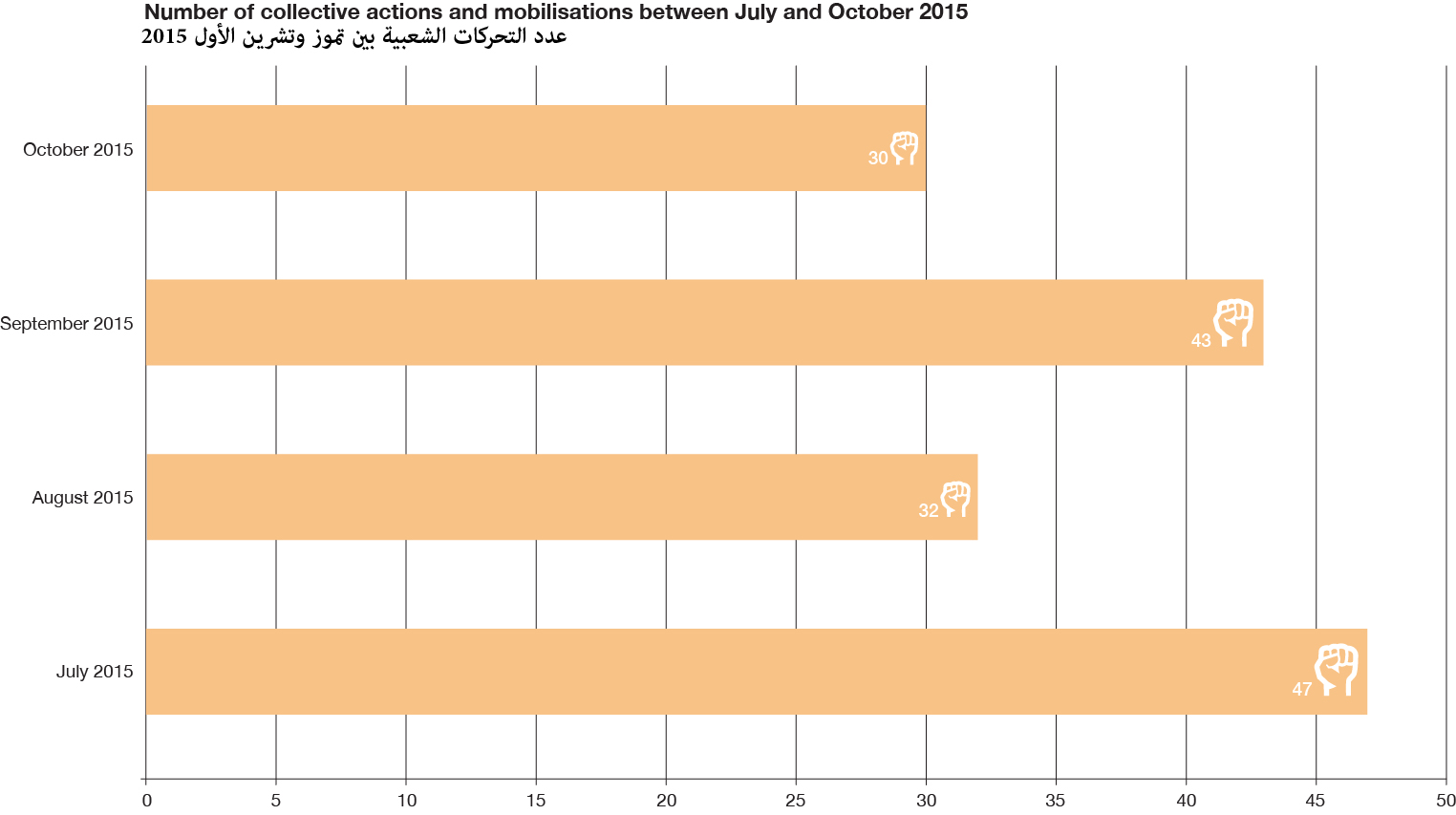

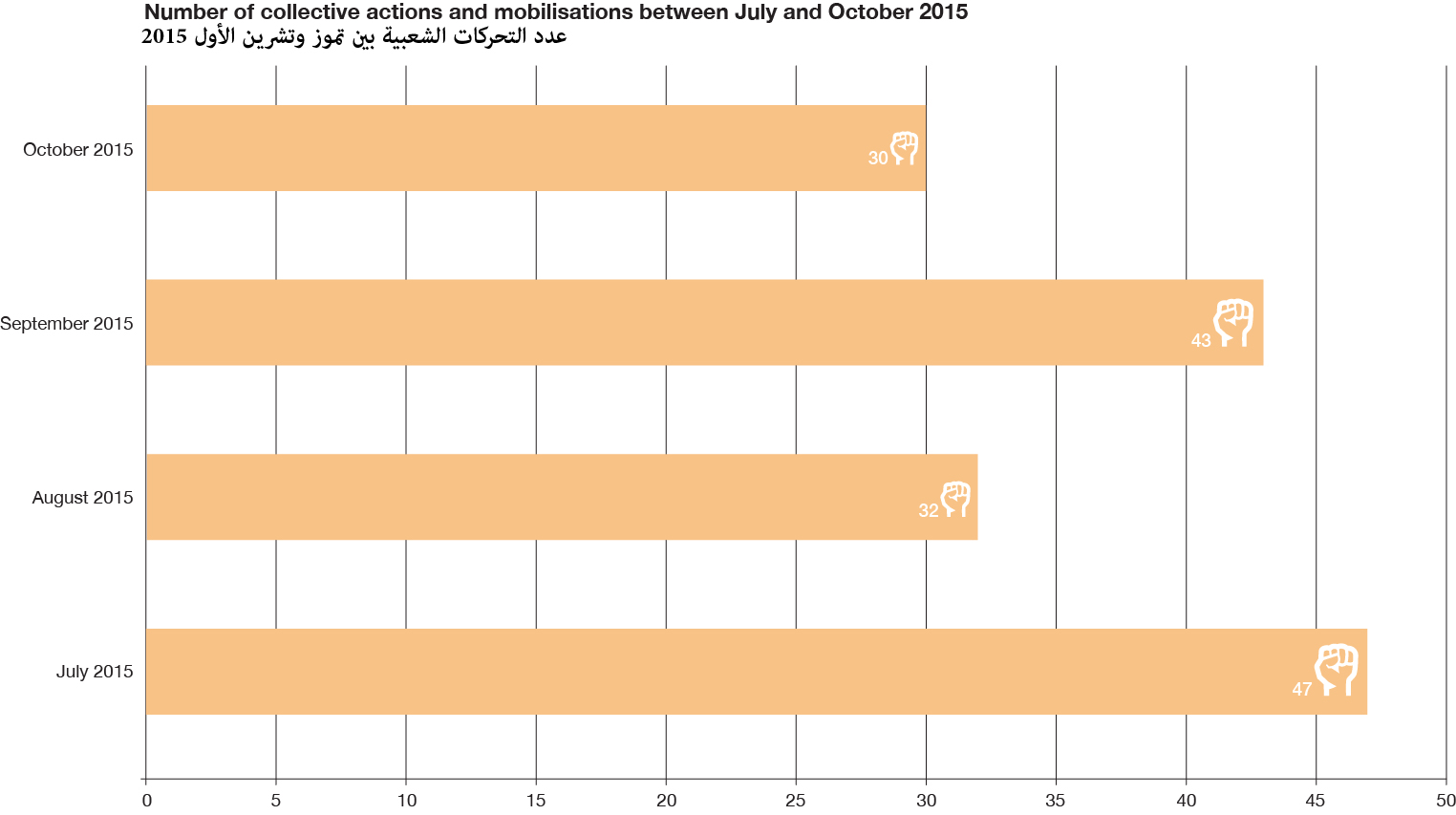

The above graph analyses Collective Actions that have taken place between the months of July 2015 to October 2015. Here, collective action encompasses, but is not limited to, actions such as sit-ins, protests, road blockages, and solidarity movements. In total, there were 152 cases of collective action incidents during the 4 months period, with 47 events taking place in July, 32 in August, 43 in September, and 30 in October.

The highest number of collective actions took place in July as it marked the beginning of thewaste management conflict prompted by the closure of the Naameh landfill on July 17th. From the conflict came countless protests, initially in Naameh, then in various locations all over the Lebanese territory. These anti-trash protests soon turned into anti-corruption protests with citizens demanding better living conditions and greater transparency from the government.

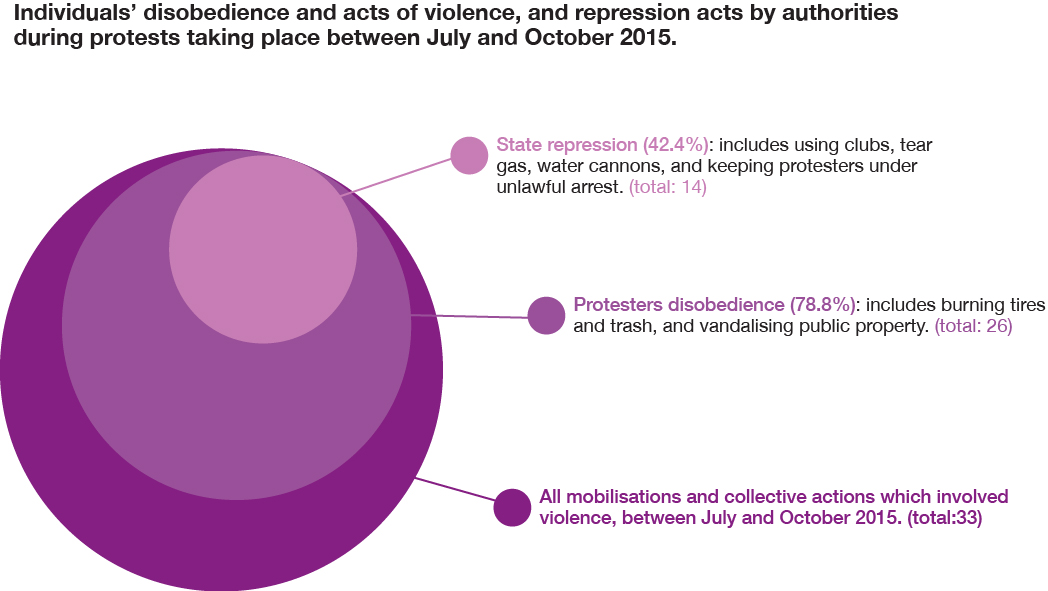

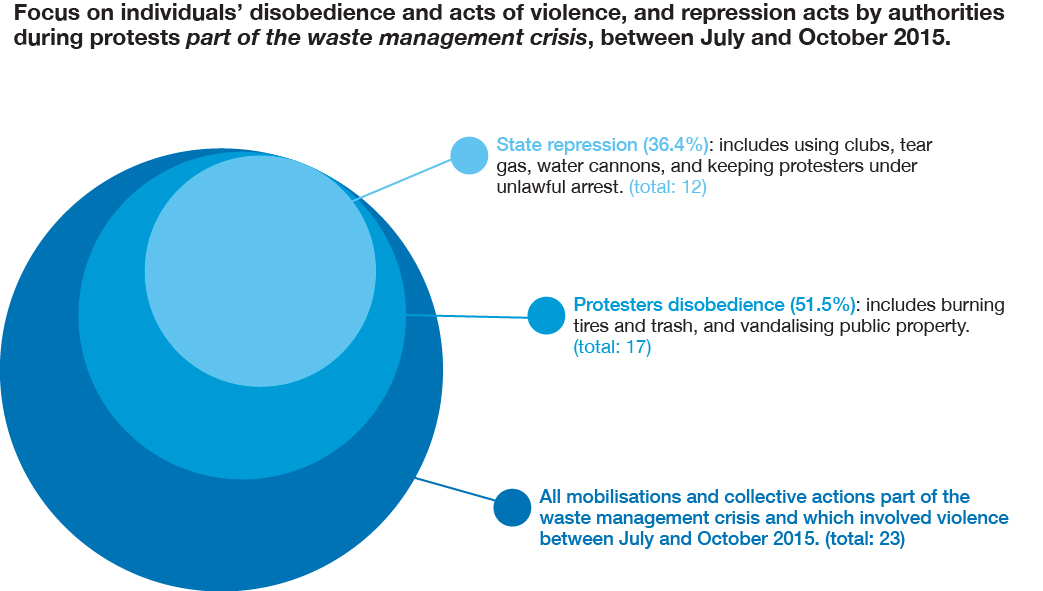

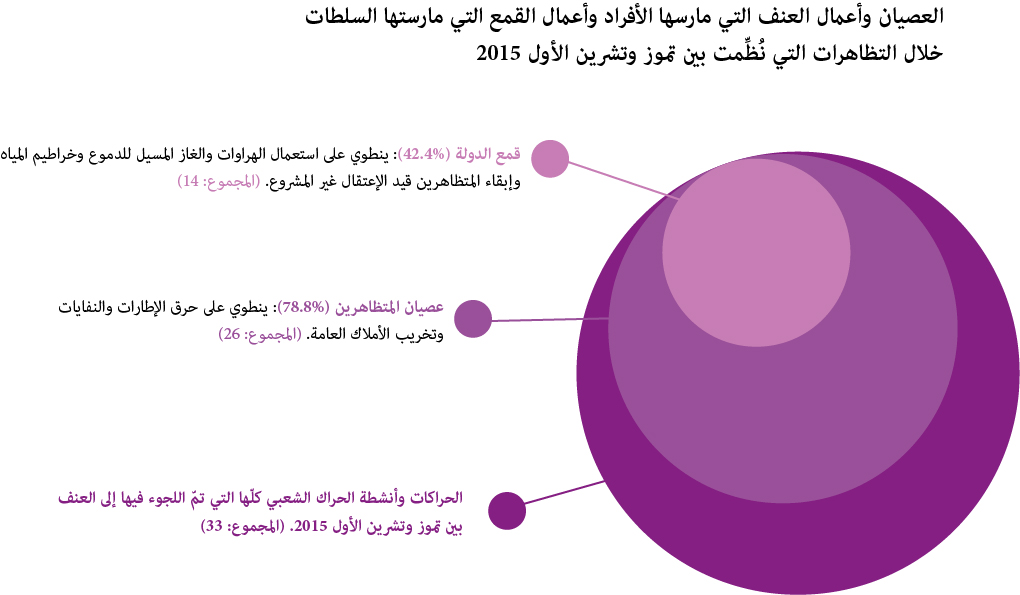

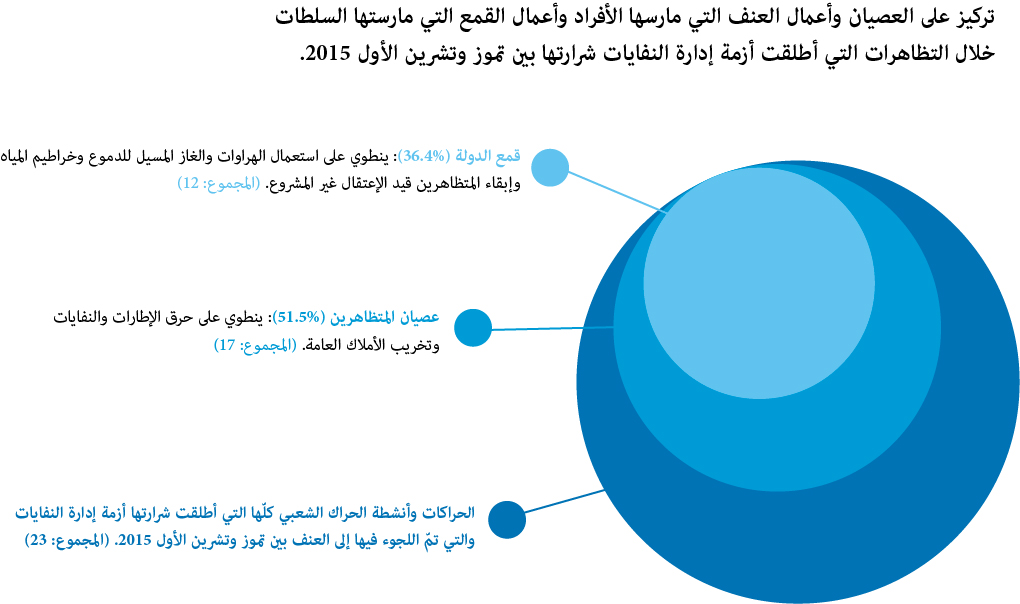

The graphs above show that mobilisations relevant to the waste management crisis involved violence the most, as opposed to other mobilisations such as the EDL workers or the families of soldiers kidnapped in Arsal. This can also be linked to the fact that most collective actions taking place between July and October had to do with the waste management conflict. 17 of these protests featured protester violence while 12 protests faced state repression. It is important to note that protester violence may be defined as civil disobedience such as protesters throwing and burning trash, as well as protesters burning tires to block roads. State repression is marked by the use of clubs, tear gas, and water cannons, while also taking into account unlawful arrests.

Notably, at least 90 protesters were arrested during these protests, with over 450 people, including ISF members, injured.

Cross-analysis ofthe numbers of collective actions in the last quarter and the increased recourse to violence from state apparatuses or some activist groups suggests a relative decrease in the number of protests, notably within the waste management crisis. In some contexts, state coercion - that has included, among others, disproportionate police violence, unlawful arrests of activists, but also infiltration of social movement by informants - has led to the radicalisation of protests, as it can be used by social movements as a political resource to push for their demands. Coercion may, as it has been observed in other coercive contexts, also lead to a certain degree of homogenisation of diverse groups participating in the same protest movement. However, the latest trends suggest that, in Lebanon, it may have contributed to dampen the waste management crisis movement. This trend may also be informed by the recourse to violence by rioters within the movement, which has led the campaign’s main organisers to distance themselves from the “troublemakers”, contributing to the creation of additional lines of fracture among the protesters and their sympathisers. The observation of the movement during the upcoming months will be crucial in understanding the long term effects of violence and repression on social movements’ tactics, strategy, and sustainability.

3. Featured report within the Conflict Mapping & Analysis project

Conflict Analysis Report - The conflict context in Beirut: the social question, mobilisations cycles, and the city’s securitisation | November 2015 Beirut

The featured report on Beirut provides an analysis of the history and current situation of the conflict context, actors, and dynamics in Beirut, Lebanon. The report includes a special focus on the social question, subsequent political and social mobilisation, gender issues, the securitisation of the city, as well as the interactions between the Lebanese host community and Syrian refugees and their unfolding within the last four years (since 2011). Read more.

4. Featured paper within the Conflict Mapping & Analysis project

Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon are often depicted as “no-law zones” that give rise to Salafist-Jihadist factions, and inter-related military networks between some Lebanese, Palestinian and Syrian groups. The Lebanese army and its intelligence apparatus are not in a totally antagonistic relationship with Palestinian actors and despite their divisions, Palestinian organizations, from Islamists to Nationalists and Leftists, cooperate with each other. This paper argues that an inter-Palestinian mediation process and a constant dialogue with Lebanese authorities are surely a precondition to face Salafist radicalization in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Read more

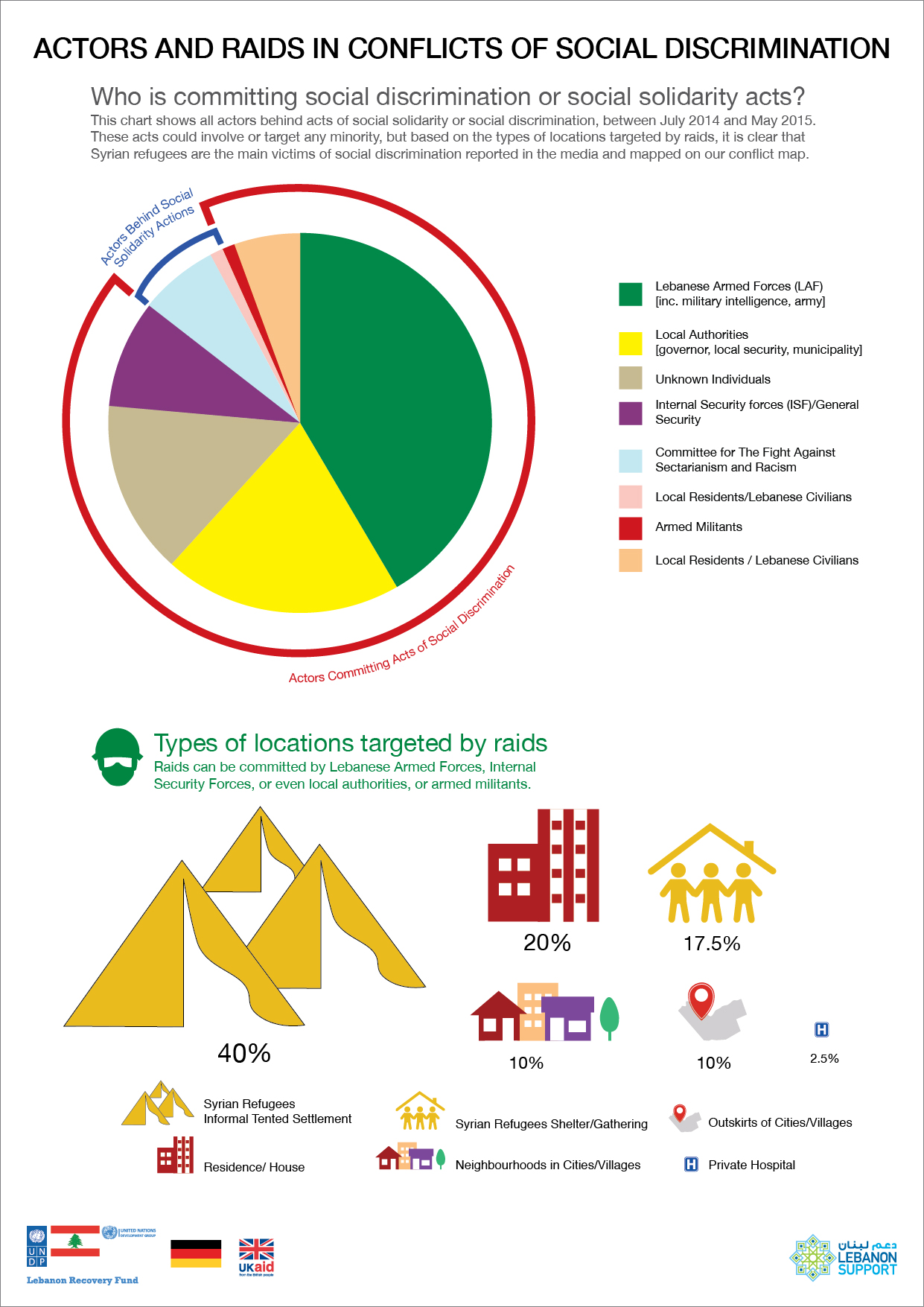

5. Featured data visualisations in Numbers & Figures

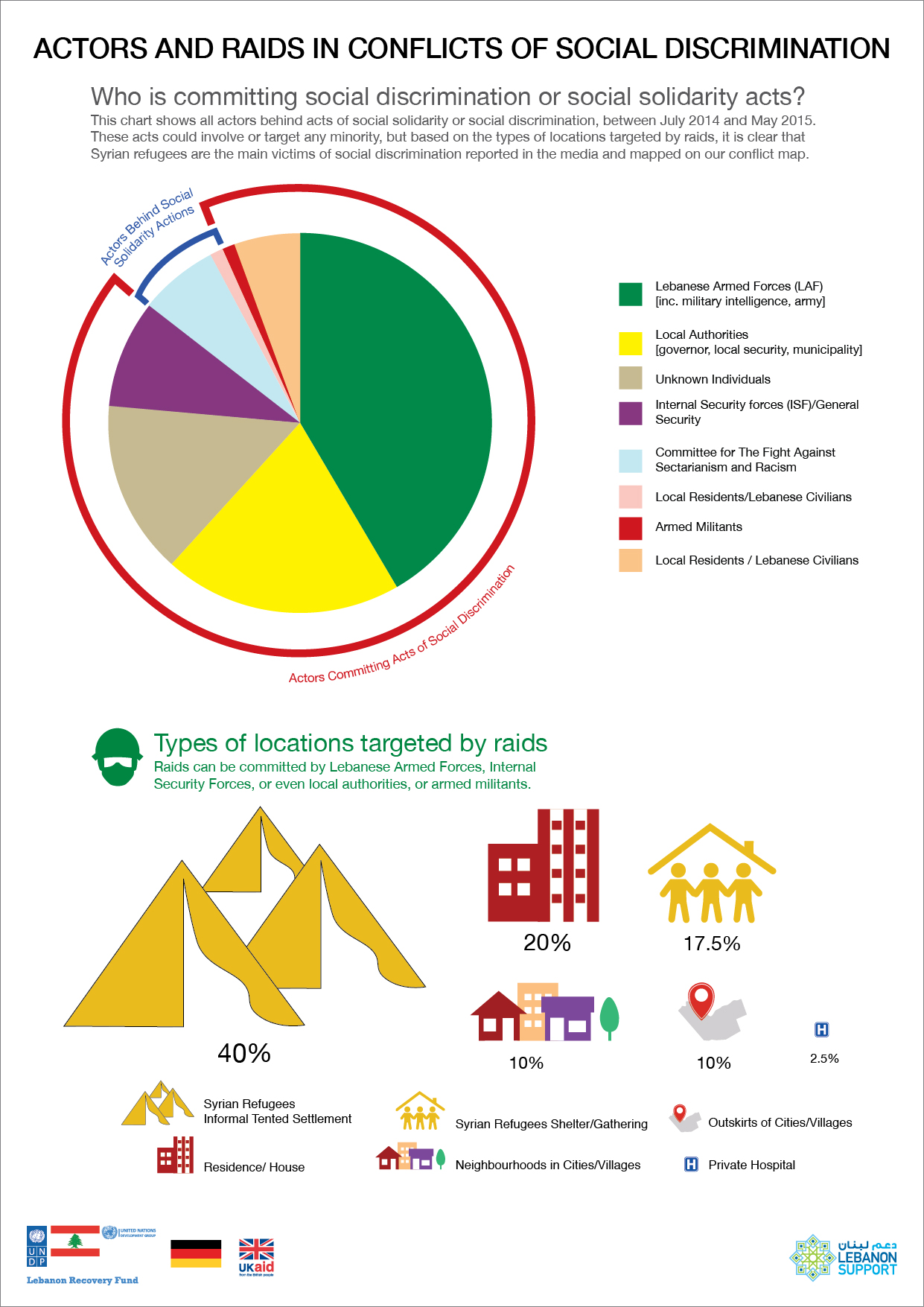

Actors and raids in conflicts of social discrimination

Overview of classifications of conflicts mapped over one year

Focus on mobilisations and collective actions in Lebanon

6. Featured Spot On Actors

Founding Date: May, 1948

Origins: The Israeli Military was officially established right after the founding of Israel on May 31st, 1948, and included pre-state Jewish paramilitary organisations (the Haganah, Palmach, Irgun and Lehi). The institution significantly developed in the first decades of the Israeli self-proclaimed statehood, by means of effective organisation, manpower and supply advantages, with the aim of ensuring the survival of the country and its people. Indeed, with the first Arab-Israeli war (May 1948-July 1949), the Israeli Military fully took on its role of “defense”, and what will later be encapsulated by the Israeli political elite as “survival”. Read more

Committee of the Families of Kidnapped and Disappeared in Lebanon

Committee of the Families of Kidnapped and Disappeared in Lebanon

Founding Date: October, 1982

Founder: Wadad Halwani, with other unknown relatives of disappeared.

Origins: The organisation was founded in 1982, seven years after the beginning of the Civil War, in response to the growing number of missing people. In 1982, Adnan Halwani, an official in the organisation for Communist Action in Lebanon, was abducted in the western portion of Beirut. His wife made a famous radio call to meet with other people in the same situation as her. Hundreds of people, mostly women, gathered after this call. A group of ten women managed to meet the Prime Minister Shafiq al-Wazzan at his residence. After this meeting, women decided to create the “Committee of the parents of the Disappeared” on October 25, 1982. Read more

7. Featured Spot On Events

Spot On Events focus on certain prominent and lasting conflicts aiming to give a broad, exhaustive overview of it, and feature interactive timelines of mapped incidents, contextual articles giving background information on the conflict, and, where it fits, actors discourses.

Arsal Conflict (starting August 2, 2014)

Tensions at Ain el-Helweh (starting August 7, 2014)

Waste Management Conflict (Starting January 25, 2014)

عن النشرة

إنّ نشرة تحليل النزاعات، وهي جزء من مشروع مسح النزاعات وتحليلها (CMA)، هي عبارة عن مبادرة أطلقها مركز دعم لبنان بدعم من برنامج الأمم المتحدة الإنمائي ووضعها على منصة المعرفة خاصّته، أي بوابة المعرفة للمجتمع المدني. تهدف هذه النشرة إلى إتاحة المعلومات والبحوث حول النزاعات في لبنان بغية تحسين فهم أسبابها الكامنة والتأثير في عملية بلورة التدخلات ووضع السياسات.

تسلِّط هذه النشرة الضوء على مروحة منتقاة من أحدث المطبوعات والمنشورات على صفحة مشروع مسح النزاعات وتحليلها، بما في ذلك الأوراق، والمقالات، والتقارير، والمواد البصرية، والمحتوى التفاعلي. هذا وتتضمّن النشرة تصوّرات مرئية لاتجاهات النزاعات الأساسية خلال الربع الأخير.

تعريف النزاع: لا ينظر مركز دعم لبنان إلى العنف من منظور إطار أمني تصاحبه أعمال العنف والعدوانية، بل يتعداه ليتمسّك بموقفه القائل إنّ النزاع هو ذات طبيعة اجتماعية وسياسية. وبالتالي، يضيء المركز على الديناميات التي تحيط بمروحة واسعة من الخلافات العنيفة وغير العنيفة، بما فيها الحركات الإجتماعية مروراً بالنزاعات التي تتورّط فيها الأقليات (الإثنية أو الدينية أو الجنسية من ضمن أخرى) بالإضافة إلى سياسات الأطراف الفاعلة المحلية أو الوطنية أو الإقليمية. إقرأ المزيد وتصفّح خريطة النزاعات التفاعلية هنا.

1. لمحة عامة عن تصنيف النزاعات بين تموز 2015 وتشرين الأول 2015

يشير الرسم البياني أعلاه إلى تقلّبات الحوادث والنزاعات الممسوحة بين تموز2014 وتشرين الأول 2015

شكّلت عمليات التحليق الجوي الإسرائيلي التي انتهكت المجال الجوي اللبناني السواد الأعظم من الإنتهاكات الحدودية الإسرائيلية. وكانت بمجملها عبارة عن طلعات إستطلاعية روتينية جاءت انتهاكاً لقرار الأمم المتحدة رقم 1701. لكنّ حالات أخرى سُجِّلت، حيث إستَعملت طائراتٌ المجال الجوي اللبناني لإطلاق صواريخ على أهداف في سورية.

شهد صيف العام 2015 إرتفاعاً في النزاعات المرتبطة بالتنمية الإجتماعية-الإقتصادية والنزاعات السياسية، والتي جاءت بمعظمها على خلفية الحراك الشعبي وما تضمّنه من تنظيم إضرابات واعتصامات وتظاهرات إعتراضاً على سياسات الدولة وقضايا العمل. فقد ارتفعت النزاعات السياسية من تموز/يوليو لغاية تشرين الأول/أكتوبر على خلفية أزمة إدارة النفايات، علماً أنّ التظاهرات تطوّرت لتشمل مروحة واسعة من المظالم السياسية ضد الحكومة اللبنانية (راجع القسم 2 أدناه). وتركّزت هذه النزاعات السياسية على وجه الخصوص في بيروت باعتبارها عاصمة لبنان ومقر الحكومة.

أما حالات العنف عبر الحدود السورية، بما فيها اندلاع اشتباكات بين الجيش اللبناني وعناصر حزب الله من جهة ومجموعات مسلحة ناشطة من سورية من جهة أخرى فتراجعت تراجعاً ملحوظاً في أواخر صيف العام 2015. غير أنّ شهر تشرين الأول سجّل تجدّداً في حوادث العنف في عرسال، مثل التفجيرات، ما أوحى بخروج عن هذا المنحى. كذلك، من الأهمية بمكان الإشارة إلى أنّ غالبية النزاعات على السلطة والحكم وقعت في طرابلس وعرسال ومنطقة البقاع الأوسع وغالباً ما تورّط فيها مسلّحون من سورية. وفي هذا السياق، يشير الجدول الزمني الخاص برأس بعلبك إلى أنّ الحوادث في هذه المنطقة بلغت ذروتها في الفترة الممتدة من أواخر كانون الثاني حتى أواخر شباط من العام 2015، مع تسجيل ما مجموعة 24 حادثاً من 23 كانون الثاني حتى 28 شباط. واللافت أنّ 4 من هذه الحوادث وقع في 23 كانون الثاني، مقابل 7 في 25 شباط و8 في 26 شباط 2015. ففي هذه الأيام الثلاثة التي اشتبك فيها الجيش اللبناني مع عناصر مسلّحة في رأس بعلبك، سُجِّل ما يزيد عن ثلثي الحوادث الممسوحة في الإطار الزمني المشار إليه أعلاه. وعلى الرغم من أنّ الإشتباكات تتواصل، فقد تراجعت أعمال العنف تراجعاً نسبياً، إذ لم تُسجَّل إلاّ 3 حوادث في رأس بعلبك في تشرين الأول. أما في ما يتعلق بالحوادث في عرسال فهي لا تزال مستمرة ومطّردة بمجملها على الرغم من تراجعها تراجعاً طفيفاً في تموز 2015، كما يبيّن جدولها الزمني. والأمر سيّان في طرابلس، حيث تتواصل الحوادث على الرغم من تراجعها منذ حزيران 2015. فمع تسجيل 14 حادثاً ممسوحاً في أيار 2015، تراجع الرقم إلى 8 فقط في حزيران ليصل العنف إلى أدنى مستوياته على الإطلاق في آب، مع تسجيل 3 حوادث فقط. تشير هذه الفئات مجتمعة إلى أنّ معدل الحوادث المرتفع الذي لا يزال يُسجَّل إنّما هو ارتدادٌ للصراع الدائر في سورية. ففي عرسال ورأس بعلبك (تقود الروابط إلى أحداث مباشرة مع تسلسل زمني تفاعلي ومقالات مرتبطة بالسياق ذات الصلة)، يبدو أنّ الحوادث المسجّلة تعود على وجه الخصوص إلى تقهقر المسلّحين من الصراع الدائر في سورية وانسحابهم نحو لبنان، وليس إلى استراتيجية متعمّدة تتبنّاها داعش أو جبهة النصرة وتقضي باستهداف لبنان.

إلى ذلك، تدهور الوضع الأمني في مخيم عين الحلوة (يقود الرابط إلى حوادث مختارة من عين الحلوة) للاجئين الفلسطينيّين في الأشهر المنصرمة. والواقع أنّ التوتر في مخيم عين الحلوة ليس بحديث العهد، بل استعر في العام الفائت أقلّه، كما تُظهر الخريطة التفاعلية والجدول الزمني. ويعود العنف المسجّل إلى أعمال العنف الفرديةوالنزاعات على السلطة والحكم (يمكن قراءة التعريف المنوط بهذه الفئات عبر هذا الرابط). ومردّ ذلك جزئياً إلى اللاجئين الفلسطينيّين الذين وصلوا إلى المخيم قادمين من سورية، الأمر الذي فاقم الأوضاع الإجتماعية والإقتصادية. فقد أذكى وصول اللاجئين الفلسطينيّين من سورية التوتر، كما هو مبيّن في هذا التقرير حول صيدا، مع العلم أنّ البيانات الإحصائية لا تزال غير متوافرة. وكما أشارت ورقة نشرها مركز دعم لبنان مؤخراً، تتلازم اتجاهات التطرّف في المخيم مع عمليات الوساطة المتواصلة بغية إنشاء قوة أمنية مشتركة بالتعاون مع الجيش اللبناني. إلى ذلك، وقعت النزاعات على السلطة والحكم على وجه الخصوص بين فتح، باعتبارها قوة أمنية، ومجموعات سلفية، مثل جند الشام. وبالإجمال، سُجِّل 18 عمل عنف فردي (في إشارة إلى الحوادث التي لا أجندة سياسية معروفة لها) خلال الربع الأخير، مقارنة بما مجموعه 28 حادثاً منذ بدء تمرين المسح في حزيران/يونيو 2014. فمنذ استهلالنا تحليل النزاعات ومسحها، سجّلنا 27 حادثاً في عين الحلوة، صُنِّفت كلّها على أنّها نزاعات على السلطة والحكم. وقد وقع 15 حادثاً منها خلال الربع الأخير، ما يؤشر على تصاعد العنف في هذه الأشهر. هذا وانطوت 7 من هذه الحوادث على رمي مجهولين قنابل يدوية في المخيم، في حين كانت 6 حوادث أخرى عبارة عن أعمال عنف قامت بها مجموعات ناشطة مثل جند الشام وداعش. ويبدو أنّ السبب وراء وقوع هذه الحوادث مردّه إلى تدهور الوضع الأمني في المخيم والمشاكل الحياتية التي يواجهها اللاجئون يومياً.

الهجوم على برج البراجنة

في 12 تشرين الثاني، نفّذ انتحاريان هجومين في منطقة برج البراجنة المكتظة بالسكان في ضاحية بيروت الجنوبية. وهذه المنطقة معروفة بانتمائها السياسي إلى حزب الله وبإيوائها مخيم برج البراجنة للاجئين الفلسطينيين. كذلك، من الأهمية بمكان الإشارة إلى أنّ هذا الحي عبارة عن منطقة سكنية وتجارية شعبية تقع قبالة طريق سريع حيوي يؤدي إلى مطار بيروت-رفيق الحريري الدولي. وفي أعقاب التفجيرات، نشرت الدولة الإسلامية بياناً تبنّت فيه الهجوم الذي أرادته لاستهداف "الرافضين المرتدين" الشيعة وأنصار حزب الله. واللافت أنّ هذا الهجوم تزامن مع اليوم الأخير من شهر محرّم الفضيل عند الشيعة.

وقع التفجيران خلال ساعة الذروة عندما كان الناس على وشك الإنتهاء من الصلاة في مسجد مجاور. فجّر الإنتحاري الأول 7 كلغ من المتفجِّرات وسط حشد بالقرب من أحد الأفران، وهو يعتلي دراجة نارية. وبعد دقائق، ومع هروع الناس إلى المكان لمعاينة ما حدث، فجّر الإنتحاري الثاني كيلوغرامين من المتفجِّرات على بعد 50 متراً.

أشار مصدر حكومي إلى أنّ الإنتحاري الثاني كان متوجِّهاً نحو مسجد الحسين. لكنّ المواطن عادل ترمس من برج البراجنة كان له بالمرصاد عندما فجّر نفسه. ومع أنّ ترمس لم ينجُ من التفجير، إلاّ أنّه أنقذ حياة المئات ممّن كانوا في المسجد في هذا الوقت. كذلك، وُجِدت في مكان الإنفجار جثةٌ تعود إلى انتحاري ثالث لم تنفجر المتفجِّرات التي كانت بحوزته.

باتت التفجيرات المزدوجة تكتيكاً شائعاً، كما حصل في طرابلس في كانون الثاني. فبعد التفجير الأول، يستغل انتحاري آخر الوضع فإما ينتظر قبل أن يفجِّر نفسه في الحشود التي تحاول الفرار من المكان عند نقطة ضيقة أو يقترب من الحشود التي تتجمهر لمساعدة ضحايا التفجير الأول قبل أن يفجِّر نفسه. والإنتحاري، بما أنّه قادر على التحرك والتنقل، يستطيع أن يتموضع في المكان الذي يراه مناسباً، في ضوء رد فعل الحشود ليلحق الضرر الأكبر في التفجير الثاني.

حدّدت وزارة الصحة عدد الضحايا بـ44، مقارنة بأكثر من 230 جريحاً كانت إصابات معظمهم حرجة. هذا وتسبّب التفجيران بأضرار جسيمة في البنية التحتية، إذ أشار أحد الشهود، وهو يستذكر ما حدث، إلى أنّ الناس "لقوا حتفهم جراء تطاير الزجاج وسقوط قطع الآجر عليهم".

ورداً على التفجيرات، أعلن رئيس الوزراء تمام سلام اليوم التالي يوم حداد وطني، في حين أعلنت وزارة التربية إقفال المدارس والجامعات. كذلك، أعلنت وزارة الصحة أنّ الدولةستتكفّل بتغطية تكاليف العلاج الطبي للمصابين.

من جهته، صرًح حسين خليل، وهو كبير المعاونين في حزب الله، من موقع الإنفجار: "ما جرى هنا جريمة .... ما جرى يؤكد أننا نسير على الطريق الصحيح بمواجهة الإرهاب". أما الأمين العام لحزب الله، حسن نصرالله، فقال في اليوم التالي للتفجير، إنّ الهجمات تعزِّز عزم حزب اللهعلى مواصلة معركته ضد الدولة الإسلامية في سورية. كما حضّ أنصاره على عدم التعرّض للاجئين السوريين إنتقاماً من الفظائع التي ترتكبها الدولة الإسلامية.

وفي غضون 48 ساعة من التفجير، أعلن وزير الداخلية نهاد المشنوق عن توقيف شبكة إرهابية من تسعة أشخاص على صلة بالهجمات. وتبيّن أنّ سبعة من المشتبه بهم من الجنسية السورية، في حين أنّ الآخرَيْن لبنانيّان. ووصف المشنوق أحد المعتقلَيْن اللبنانيَّين، إبراهيم جمال، على أنّه انتحاري مفترض اعتُقل في طرابلس عندما لم ينفجر حزامه الناسف. وقال هذا الطرابلسي للمحققين إنّه جزء من خلية لداعش أُرسلت من سورية إلى لبنان قبل يومين بغية تنفيذ الهجمات، مع العلم أنّ المحققين لم يتحققوا من هذه المعلومة بعد. أما الموقوف اللبناني الثانيالذي عُرِّف عنه بالأحرف الأولى ع.س. فساعد على تهريب انتحاريَّين من سورية إلى عرسال. وبحسب الوكالة الوطنية للإعلام، صادرت القوى الأمنية، عند مداهمتها منزل المهرِّب في اللبوة البقاعية، وثائق مزورة وسيارة يُشتبه في أنّها استُعملت لنقل الإرهابيين.

هذا ووُصف اثنان من السوريين السبعة على أنّهما انتحاريان مفترضان لكنّهما لم يتورطا في الهجوم بسبب تغيير في الخطة.

وفي 15 تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر، اعتقل الأمن العام اللبناني إبراهيم أحمد رايد والسوري مصطفى أحمد الجرف بتهمة تمويل تفجيرات برج البراجنة والتخطيط لها، من دون أن يتضح ما إذا كانا من ضمن التسعة الذين أعلن المشنوق عن توقيفهم.

إلى ذلك، كشف المشنوق أنّ الإنتحاريين المهربين قد اتخذوا ملجأ لهم في مخيم برج البراجنة وفي شقة في الأشرفية حيث قاموا بتجميع الأحزمة الناسفة قبل تنفيذ الهجمات. وكان الإنتحاريون الخمسة يعتزمون الدخول إلى مستشفى الرسول الأعظم في برج البراجنة لكنّهم عدلوا عن خطتهم بسبب الإجراءات الأمنية المشدّدة في محيط المستشفى.

وإذ شكّل هذا الحادث وتسلّل داعش المفترض إلى بيروت صدمة لكثيرين، من الأهمية بمكان الإشارة إلى أنّ الجيش اللبناني ينخرط دوماً في اشتباكات في محافظة البقاع وتحديداً في رأس بعلبكوبعلبك وعرسال. كما يُعتقد أنّ العنف الذي لم ينفك يهز طرابلسخلال السنوات القليلة الماضية على خلفية النزاع السوري يغذي التعاطف مع الجهاديين، ما يسمح بتطرّف المواطنين، مثل المتواطئَيْن اللبنانيَّيْن رهن الإعتقال. واللافت أيضاً أنّه في اليوم نفسه لوقوع الهجمات في برج البراجنة، وجد الجيش اللبناني في طرابلس عبوة ناسفة بزنة 10 كلغ عمل على تفكيكها.

2. منحى الصراع: تركيز على الحراك الشعبي

يحلِّل الرسم البياني أعلاه أنشطة الحراك الشعبي التي وقعت بين تموز 2015 وتشرين الأول 2015. ويشتمل هذا الحراك، على سبيل المثال لا الحصر، على خطوات، مثل الإحتجاجات، والتظاهرات، وقطع الطرق، وحركات التضامن. وبالإجمال، سُجِّل 152 عملاً من هذا النوع خلال فترة الأربع أشهر، وقع 47 منها في تموز مقارنة بـ 32 في آب و43 في أيلول و30 في تشرين الأول.

ولعلّ العدد الأكبر من أنشطة الحراك الشعبي حصل في تموز/يوليو بالتزامن مع نشوب أزمة إدارة النفايات على خلفية إقفال مطمر الناعمة في 17 تموز/يوليو. وأدى هذا النزاع إلى عدد لا يحصى من مظاهر الإحتجاج بدأت في الناعمة قبل أن تتوسّع لتشمل مواقع متعدِّدة في مختلف أنحاء لبنان. وسرعان ما تحوّلت هذه التظاهرات المندِّدة بالنفايات إلى احتجاجات ضد الفساد، مع مطالبة المواطنين بتحسين أوضاعهم المعيشية وتعزيز شفافية الحكم.

يُظهر الرسمان أعلاه أنّ الحراك المتصل بأزمة النفايات كان الأكثر عنفاً مقارنة بالحراكات التي دعا إليها المياومون في شركة كهرباء لبنان أو أهالي العسكريين المخطوفين في عرسال. ولعلّ السبب في ذلك يعود إلى أنّ معظم المظاهر الإحتجاجية التي وقعت بين تموز وتشرين الأول كانت على صلة بإدارة النفايات. لجأ المتظاهرون إلى العنف في 17 من هذه التظاهرات، في حين قُمعت 12 أخرى من قبل الدولة. من النافل القول إنّ لجوء المتظاهرين إلى العنف يتمثّل في أعمال العصيان المدني، كأن يرموا النفايات ويحرقوها أو يقفلوا الطرقات بواسطة الإطارات المشتعلة. أما قمع الدولة فيتمثّل في استعمال الهراوات والغاز المسيل للدموع وخراطيم المياه، بالإضافة إلى عمليات الإعتقال والتوقيف غير المشروعة.

هذا ومن المثير للإهتمام اعتقال ما لا يقلّ عن 90 متظاهراً خلال هذه التظاهرات، فضلاً عن إصابة أكثر من 450 شخصاً، من بينهم عناصر في قوى الأمن الداخلي.

تشير مقاطعة عدد التحركات الإحتجاجية في الربع الأخير مع تنامي اللجوء إلى العنف من قبل أجهزة الدولة أو بعض مجموعات الناشطين إلى تراجع نسبي في عدد التظاهرات، ولاسيما تلك المتصلة بأزمة إدارة النفايات. ففي بعض السياقات، يؤدي القمع الذي تمارسه الدولة والذي يتخذ اشكالاً عدة - منها لجوء عناصر الشرطة إلى العنف بصورة غير متكافئة وتوقيف الناشطين بصورة غير مشروعة وأيضاً تسلل المخبرين إلى الحركات الإجتماعية - يؤدي إلى تطرّف التظاهرات، وهي أداة سياسية يمكن للحركات الإجتماعية الركون إليها للدفع بمطالبها. في المقابل، قد يؤدي القمع، كما هو ملاحظ في سياقات قمعية أخرى، إلى درجة معينة من التجانس بين المجموعات المتنوِّعة المشاركة في الحركة الإحتجاجية نفسها. لكنّ الإتجاهات الأخيرة في لبنان تشير إلى أنّ هذا القمع قد يكون السبب وراء تقويض الحركة التي نشأت على خلفية أزمة النفايات، ولاسيما مع لجوء مثيري الشغب إلى العنف ضمن الحراك نفسه، الأمر الذي دفع بمنظمي الحملة أنفسهم إلى النأي بأنفسهم عن "المشاغبين"، ما زاد الشرخ بين المتظاهرين والمتعاطفين معهم. لهذا، لا بد من مراقبة الحراك خلال الأشهر القادمة لفهم آثار العنف والقمع طويلة الأجل على تكتيكات الحركات الإجتماعية واستراتيجياتها واستدامتها.

3. تقرير مختار ضمن مشروع مسح النزاعات وتحليلها

تقرير تحليل النزاع | تشرين الثاني 2015 بيروت

يحلِّل التقرير المختار حول بيروت تاريخ سياق النزاع ووضعه الحالي بالإضافة إلى أطرافه وديناميكياته في بيروت، لبنان. كما يضع التقرير نصب عينيه المسألة الإجتماعية والتعبئة السياسية والإجتماعية اللاحقة وقضايا النوع الإجتماعي وضمان أمن المدينة، فضلاً عن التفاعلات بين المجتمع المضيف اللبناني واللاجئين السوريين وتطورها خلال السنوات الأربع الماضية (منذ العام 2011). إقرأ المزيد.

4. ورقة مختارة ضمن مشروع مسح النزاعات وتحليلها

بين التطرف والوساطة: رسم خريطة سياسية لمخيمات اللاجئين الفلسطينيين في لبنان*

غالباً ما يُنظر إلى مخيمات اللاجئين الفلسطينيين في لبنان على أنّها "مناطق خارجة عن سلطة القانون" تنمو فيها الفصائل السلفية الجهادية والشبكات العسكرية المترابطة بين بعض المجموعات اللبنانية والفلسطينية والسورية. والواقع أنّ الجيش اللبناني ومخابراته ليست في علاقة عدائية بالكامل مع الأطراف الفاعلة الفلسطينية. أما المنظمات الفلسطينية، اإسلامية كانت أو قومية أو يسارية، فتتعاون مع بعضها البعض على الرغم من انقساماتها. ترى هذه الورقة أنّ الوساطة بين الفلسطينيين وتواصل الحوار مع السلطات الفلسطينية يشكِّلان شرطاً أساسياً مسبقاً لمحاربة التطرف السلفي في مخيمات اللاجئين الفلسطينيين في لبنان. إقرأ المزيد

5. بيانات بصرية مختارة: بالأرقام

الأطراف الفاعلة والمداهمات في النزاعات المرتبطة بالتمييز الإجتماعي

لمحة عامة عن تصنيف النزاعات الممسوحة خلال عام

6. إضاءة مختارة على الأطراف الفاعلة

تاريخ التأسيس: أيار 1948

النشأة: تأسّس الجيش الإسرائيلي رسمياً مباشرة بعد قيام دولة إسرائيل في 31 أيار/مايو 1948 وضمّ في عداده منظمات شبه عسكرية يهودية كانت ناشطة قبل قيام الدولة (مثل هاجاناه، وبلماح، وإرجون، وليهي). تطوّرت المؤسسة تطوراً جوهرياً في العقود الأولى من إعلان إسرائيل قيام دولتها بفضل التنظيم الفعّال والقوة البشرية وتفوق المؤسسة على مستوى الإمداد، وذلك بغية ضمان بقاء البلد وشعبه. وبالفعل، مع الحرب العربية-الإسرائيلية الأولى (أيار/مايو 1948-تموز/يوليو 1949)، اتخذ الجيش الإسرائيلي لنفسه دوراً "دفاعياً" وما ستعرِّفه النخبة السياسية الإسرائيلية لاحقاً بـمفهوم "البقاء". إقرأ المزيد

لجنة أهالي المخطوفين والمفقودين في لبنان

لجنة أهالي المخطوفين والمفقودين في لبنان

تاريخ التأسيس: تشرين الأول 1982

المؤسِّسة: وداد حلواني مع أقارب مجهولين آخرين للمفقودين

النشأة: تأسسّت المنظمة في العام 1982 بعد سبع سنوات على اندلاع الحرب الأهلية رداً على تنامي عدد المفقودين. ففي العام 1982، اختُطف عدنان حلواني الذي كان مسؤولاً في منظمة العمل الشيوعي في لبنان في بيروت الغربية. أجرت زوجته اتصالاً هاتفياً ذائع الصيت عبر الإذاعة، داعية إلى لقاء أشخاص آخرين في الوضع نفسه مثلها. لبّى مئات الأشخاص، معظمهم من النساء، النداء. تمكّنت مجموعة من عشر نساء من لقاء رئيس الوزراء شفيق الوزان في مقر إقامته. وبعد هذا الإجتماع، قرّرت المجموعة إنشاء لجنة أهالي المفقودين في 25 تشرين الأول 1982. إقرأ المزيد

7. إضاءة على الأحداث

في هذه الإضاءة على الأحداث تركيز على بعض النزاعات البارزة والدائمة لإعطاء لمحة عامة شاملة ووافية عنها. وفيها أيضاً استعراض تفاعلي متسلسل زمنياً للأحداث التي تشملها الخرائط، فضلاً عن بعض المقالات التي تُقدِّم معلومات خلفية حول النزاع وخطابات الأطراف، حيث أمكن.

النزاع في عرسال (اعتباراً من 2 آب 2014)

التوتر في عين الحلوة (اعتباراً من 7 آب 2014)

النزاع حول إدارة النفايات (إعتباراً من 25 كانون الثاني 2014)