Prisms of Political Violence, ‘Jihads’ and Survival in Lebanon’s Tripoli

In the framework of the recruitment of Syrian and Lebanese fighters combating today in Syria, this paper aims to further problematise the processes in which individuals decide to disrupt their ordinary lives to engage with “Jihadist” armed groups. Such processes are frequently studied and tackled by government programmes and NGO practices aimed at the “rehabilitation” of former fighters in various countries ranging from Muslim majority states to European or North American states. Likewise, some terrorism scholars still tend to trace a linear path to identify the social and psychological causes which push individuals to join militant groups, and trace the causes which, in some cases, lead to subsequent disengagement from fighting and the ideology involved. This study rather shows the cyclic and changing nature of life choices and circumstances which influence Jihadist fighters and supporters. By doing so, it embraces the scholarly approach according to which “extremist” armed groups should be studied and understood as any conventional social group. In specific, this primary research is based on ten in-depth interviews conducted in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli with Syrian and Lebanese ex-fighters, and with sympathisers of the so-called "Jihadi ideology" who never took up weapons. To interpret the narratives I collected, I will intentionally draw on both critical and mainstream security-focused bodies of literature on political violence, “radicalisation”, and extremism. While the experiences recounted by the ex fighters will be analysed through the two constructed categories of contingency and intentionality, the Jihadist supporters who never joined an armed group rather point to how there is no linear and unilateral progression from “extremist” beliefs to violence. The survival of such forms of political violence, ultimately, challenges the survival of politically biased knowledge and the programmes that the latter informs.

To cite this paper: Estella Carpi,"Prisms of Political Violence, ‘Jihads’ and Survival in Lebanon’s Tripoli", Civil Society Knowledge Centre, Lebanon Support, 2015-12-01 00:00:00. doi: 10.28943/CSKC.003.300011

[ONLINE]: https://civilsociety-centre.org/paper/prisms-political-violence-‘jihads’-and-survival-lebanon’s-tripoli

Introduction1

This paper aims to question the mainstream linear processes according to which individual ordinary life is disrupted by engagement with Islamist armed groups. This disruption is then addressed and diverted towards disengagement from armed groups via intervention of particular strategies. These linear processes frequently underlie the programmes aimed at “rehabilitating” Jihadist fighters, which are implemented in countries ranging from Muslim majority states to North American and European states.2 Likewise, terrorism scholars tend to trace a linear path to identify the experiential and psychological causes pushing individuals to join militant groups as well as the causes which, in some cases, lead to subsequent disengagement from fighting and the ideology involved. This paper rather illustrates how engagement and disengagement are much more muddled and complex processes, circularly triggered by factors of contingency and intentionality. Moreover, it supports the belief of some scholars3 that, in a bid to understand violent actions, non-violent actions need to be tackled first, and, furthermore, the study of radical engagement does not sociologically differ from the study of conventional engagement.

NGO activities have a reputation of being successful in ruling out re-engagement with extremist armed groups.4 These activities vary from projects focused on community engagement, as done in Algeria, to information campaigns meant to inculcate - and assert once and for all - “moderate Islam”, as done in Jordan and Morocco. Notably, NGOs in Egypt organised prison debates, whilst NGOs in Saudi Arabia and Yemen sought to render the “ex-radicalised” employable and family responsible to eschew re-engagement in extremism. It is also common belief of experts and the general public that the very causes of radicalisation should be eradicated in order to avert returns to violent extremism.

The troubled socio-political history of North Lebanon’s Tripoli, which has historically become a satellite of Syrian political turmoil and repression, emerges here as an illustrative case for highlighting the nonsensical character of potential rehabilitation programmes in providing life alternatives to the interviewees. In fact, providing individuals with assets or life opportunities – like a job or a partner and kids – does not necessarily mean that those more exposed to active violent extremism will no longer feel committed to taking up arms and joining the battle in Syria. Cyclic life crises may hit the immediate certainties that some of these rehabilitation programmes provide to avert re-engagement.

This paper shows how the scholarly constructed process of “de-radicalisation” does not necessarily come with ideological disengagement from violent extremism. Those among the interviewees who had previously fought did not abandon a particular environment or ideology when they quit fighting. They rather went back to the same deprived society that they grew up in. They simply moved from one role to another, a behaviour also observed by Horgan.5 I therefore argue that real disengagement with guarantee of non-return – a dilemma that is vexing present scholars - struggles to subsist. This can be mainly explained by virtue of the political history of North Lebanon, in which the city of Tripoli has long represented the cradle of Lebanese pan-arabism, an “anti-state” microcosm countervailing the French-created non-Muslim State of Lebanon based in Beirut, allegedly offering the only hope for political modernisation but mainly neglecting the peripheral regions outside the capital. In this framework, Tripoli epitomised a pan-Arab entity, where almost half the population6 from all North Lebanon resides: a historically neglected region with socio-economic reasons to be against the central State.7

Through the construction of the two broad categories of “life contingency” and “individual intentionality” as pull factors,8 I align myself with an articulated understanding of political violence as an individualistic phenomenon, relying on the life circumstances of the fighters and their supporters,9 and varying across historical areas, ideologies, and regions of the world.10 Moreover, this paper confirms how what is commonly defined as “extreme forms of violence” (i.e. Jabhat an-Nusra11 in this specific case) is influenced by domestic, regional, and international politics.12

Throughout this paper, I will draw on the literature of what is generally defined as “terrorism” (resorting to violence to kill civilians while pursuing a political agenda). Nevertheless, although being a terrorist certainly implies the idea of being a “radical,” a radical is not necessarily a terrorist.13 The paper will proceed by adopting the term “Jihadist” – someone using extreme forms of violence to pursue specific aims in the name of Jihad, endemically meant as a worldview and a personal struggle – rather than “terrorist.” In fact, clarity is also needed in employing the term “Jihadist”, which here simply refers to the way in which the interviewees have defined themselves and their ideological approach to fighting or supporting the fighting. Their life circumstances, inherently associated with contingency, will be particularly highlighted in the data analysis, in the effort to avoid homogenising different individuals on the basis of their common features: active forms of violence, and Islam as a - further, and often not primary - moral legitimacy for fighting or supporting the Jihadi ideology, which will be defined later.

It is noteworthy that this study does not question the rehabilitation programmes as an inherently failing strategy from a scientific perspective, but rather aims to provide intuitive insights based on empirical findings which may undermine the very foundational logic of such programmes. Tripoli represents an insightful case study to question such constructed reifications of radicalisation.

The Tripoli Context

The prolonged and escalating Syrian crisis witnessed an unprecedented participation of Jihadist fighters from Europe and other countries in the Middle Eastern and North African region. Such brigades range from alleged extreme groups, the greatest among them being the “Islamic State” (commonly called in Arabic tanzim ad-dawleh),14 to lesser radical groups such as Jabhat an-Nusra and other smaller groups still deemed as extremists, like Ahrar ash-Sham, Liwa’ at-Tawhid, and Jeiysh al-Islam. Several other sub-groups under the umbrella of the Free Syrian Army, FSA (al-Jeiysh al-Horr) are considered as more moderate, and are labelled as “terrorists” only by the Assad regime and the regime’s allies. While these moderate sub-groups enjoyed large western and Arab Gulf support on a diplomatic level, the most extreme groups like the “Islamic State” and Nusra seem to have been more sustained on the level of resources.

Among multiple historical and political reasons and views, the proliferation of Jihadism in Syria and Iraq has been deemed as a consequence of the American-friendly regime of Nuri al-Maliki in Iraq and his “mis-government”, as well as the release of large numbers of Jihadists from the Syrian jails at the outset of the Syrian uprisings in 2011, while secular and moderate political activists and revolutionaries are still detained.

Likewise, it is unthinkable to sociologically discuss Jihadism and the reasons for joining or supporting the armed groups in Syria in Tripoli without framing this analysis in the historical past of the city and its periphery.

In order to interpret the local relationship of Lebanese and Syrian generations in North Lebanon with Islam-coloured political violence, it is paramount to recall the Syrian presence in the country from 1975 until 2005. In the wake of Lebanese protests and the so-called March 14 “Cedar Revolution” in February and March 2005, the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad decided to withdraw his troops, which, at that time, was meeting the US geopolitical interests. The Syrian national army’s soldiers in Lebanon, especially in the North, were known to rape women, torture prisoners, and detain political opponents.15 Akkar’s people can still remember the geography of the Syrian occupation (officially called al-wikala as-suriyya, “the Syrian protection”), which used to stifle economic development in the region and crack down on any political future other than the submission to Syrian officials and interests.16

Furthermore, the Tripoli neighbourhood of Bab at-Tabbaneh was destroyed in 1986 by the Syrian regime without being reconstructed. At that time, between 300 and 800 people were killed in the neighbourhood. The urbicide and massacres of civilians are still cause of resentment and hatred towards Assad’s supporters for all inhabitants of this Sunni-majority district.

What precedes such massive destruction? The oppression and exclusion of Sunni urban poor in Lebanon, especially in the North, has a political explanation.17North Lebanon’s Sunni grassroots were socially the “losers” of the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990), which was de facto won by Syria, extending its presence in Lebanon with the excuse of protecting stability (the so-called pax syriana) along with ambiguous Lebanese political élites and other Syria’s allies - mainly the major Shiite political party Hezbollah, which, at that time, was still seeking to trump the second Shiite party Harakat Amal.

Syria set the Sunni urban poor aside in the northern region politically and economically:18 the Northern lower classes were enjoying neither the support of the central state nor of local political actors unlike the South, where Hezbollah was already developing a large administrative role at a local level. The “Sunni” socio-political space in Tripoli was rather fragmented, and this neither helped in countering the Syrian administrative totalitarianism in North Lebanon nor managed to create a solid and cohesive political alternative able to confront the Syrian army. Likewise, the main Sunni political party Taiyyar al-Mustaqbal (“the Future Current”) has always lacked a clear militant cause, which, similarly to Hezbollah’s Resistance against Israel, can raise and preserve social empathy and cohesion. Consequently, the Mustaqbal party has fostered no homogenisable political vision.19

Moreover, the rampant transnational Sunni Islamism led locals to identify to a greater extent with other oppressed Sunnis in the region and worldwide,20therefore preventing a stronger structuring of the Sunni community and leadership in the North and in all Lebanon.

By using security arguments, Tripoli and the whole Northern region were set on the back-burner in regards to economic empowerment and reconstruction, and the Sunni poor remained marginalised by state and non-state policies and services. This enlarged the gap between the wealthy and the poor in the North, as well as between the Northern Christian and Sunni communities.21 The closure of the Qiliy‘at Airport a few kilometres from Tripoli, active for civilian charter flights over the years of the civil war, represented a deliberate act of curbing domestic economic prosperity .22

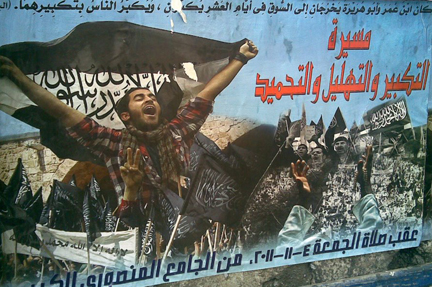

Opposition to the Assad’s regime and its ally Hezbollah found very fertile ground in this political environment, where the wounds of the Syrian oppression (az-zolm as-suri) are still fresh and painful. In this regard, Harakat at-Tawhid al-Islami (the Islamic Unification Movement) formed by ‘Ali Akkawi with pro-Palestinian and anti-Syrian sentiments in the early 1980s, was meant to end the longstanding deprivation and predicament of the Tripoli neighbourhood of Bab at-Tabbaneh.23 Swelled by an influx of Syrian Islamists escaping Hafez al-Assad’s repression of the Muslim Brotherhood, Tawhid seized control over a large part of Tripoli until it was ended in 1986 by the Syrian forces with the above mentioned destruction of Bab at-Tabbaneh. Similarly, the 1964-born Lebanese branch of the Muslim Brotherhood al-Jama‘a al-Islamiyya (“the Islamic Association”) created the idea of an Islamic state, a political project in opposition to the secular Arab nationalist trends spread out at that time in Lebanon. The chronic disaffection of Sunni Northern Lebanese towards the state and other welfare organisations incubated widespread feelings of frustration among these political movements in Tripoli until today.

These political tendencies have found their instrument of expression and mobilisation in Tripoli after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution and the developing of its internal and external dynamics. The March 14 coalition, led by the Sunni leader Saad Hariri at the helm of al-Mustaqbal Party, conveniently capitalised on the predicament and the victimisation of the Syrian refugees fleeing Assad’s bombing to neutralise its own political agenda and construct a humanitarian façade, while accusing the March 8 parties24 and their welfare organisations of not mobilising their resources for the Syrian newcomers.

In this environment, I met ten informants, whose families were still carrying the weight of the torture, assassination, or imprisonment of one of their family members during the time of Hafez al-Assad or, from 2000 onwards, during the regime of his son, Bashar.25 Hence, in this context, political violence can be interpreted as a home-grown response to internal political, economic, and social oppression. As my field research seems to suggest, radicalisation turns out to be nonsensical when represented as a process disrupting normality: it is rather a construction of politically de-institutionalised violence which allows global politics to influence it and conveniently evaluate the propensity to be “healed”.

The longstanding presence of Syrian migrant workers in Tripoli and Akkar,26 who integrated with the local urban fabric of the mainly Sunni poor, cannot be overlooked. Some of these migrants, economically exploited and often mistreated, have represented an anchor of hope for incoming Syrian refugees who continued to pour into North Lebanon as a result of the Assad regime’s repression.

Methodology

Ten in-depth interviews have been conducted in the city of Tripoli in May 2015 in private spaces (six Syrian and four Lebanese men between the ages of 20 and 40). Among the interviewees, only five used to fight in Syria (one Lebanese and four Syrians). More specifically, three of them had previously been a part of Jabhat an-Nusra, while one was a part of the FSA, and another of the Jund ash-Sham brigade. The remaining five, who never took up arms in the ongoing Syrian conflict, were still included in the research sample in accordance with a wider self-definition as “Jihadist:” supporters of the Jihadi ideology, of the fighters in Syria and their political and confessional cause. Moreover, the interviewees who never took up arms served as a paradigm of reference for scrutinising the muddled process from “extremist beliefs” to armed fighting. It is also worth specifying that all the interviewed Syrian ex fighters owned kins in the city of Tripoli and surroundings.

The following analysis is based on the encounters with these interlocutors, who spontaneously decided to contribute to this research project under condition of anonymity and identity protection by changing their names, their provenance, and their age. I managed to access the area and meet with the interlocutors through three local gatekeepers in different neighbourhoods of Tripoli (Zahriyye, Abu Samra, and Bab at-Tabbaneh).

The interviewees were initially reluctant to discuss about involvement and sentiments on their “mission” or thinking, since the interviewer – that is myself - was considered as part of the international community, whose inaction is also to be blamed for the ongoing massacres in Syria. Here the typical common ground for research participation and solidarity, which usually creates ethnographic resonance27 between the “informant” and the “informed”, was torn up. It is also necessary to note that great reluctance to share past experiences was only initially encountered when dealing with the ex fighters. The intermediary role of the gatekeepers helped me to positively appear as a possible carrier of their voice - locally described as unheard - outside of their community.

I have met with the interviewees only once. Although all interviewees eventually decided to participate on condition of identity protection - which points in reality to an act of trust - the impossibility of going deeper into mutual knowledge in that frame unavoidably influences the degree of intimacy and trust that the interviewees developed towards me. This, in turn, also affects the research standards of recurrence and consequent representativeness of the sampled data. While the answers provided are also likely to be read in rhetoric terms - as they may have wanted to conceal some details to someone they were not intimate with - such answers are still optimal conveyors of diverse human behaviours and thinking, which can produce insightful findings despite their problematic empirical verifiability.

I have classified my data by constructing two categories of knowledge (contingency and intentionality) in order to make my analysis more manageable and understandable. Nonetheless, this has been done with the full awareness that human intentions are often shaped in life by contingent factors, as contingency plays a role between previous and future series of individual intentional acts. It is noteworthy that the notion of “contingency” should be interpreted as differing from that of “aleatory”, as contingency still carries specific reasons, stemming from contextual factors, and leading to specific material circumstances. While Jihad was mostly identified as a political struggle in the accounts provided, the data analysis28 can be heuristic even if such a struggle is used as a mere rhetoric. In other words, the analysis can still offer insights on how the interviewees have decided to perform in the encounter, and how to verbally convey their experiences during our encounter.

Data Analysis and Discussion

1. Which Jihadism?

Anyone who fights for what he believes is Jihad is a mujahid, or “Jihadist”. However, according to scholarly sources, whoever supports and encourages Jihad can also be defined – or defines oneself - as such. It is in this sense that the term “Jihadist” will be used throughout this paper. I reiterate that Jihadism and terrorism should not be considered and used as synonyms, although they both constitute a means to a specific end, and not an end itself.29 In specific terms, Jihadism implies ideologically and physically fighting against political foes for a major political change, by using a “theologically legitimate and instrumentally efficient method.”30

On the basis of the views of my research participants, I feel entitled to rephrase that Jihadism is not a single analytical category to discuss events on the ground in Syria or elsewhere. Jihadism is definable with respect to the geography one discusses, although it is generally identifiable with religious and political labels adopted to mark “the other” with respect to the Self.

With regard to this, Ahmed, a 28 year-old Syrian ex FSA fighter, claimed how self-definition should be prioritised in accounts about Jihad. His statement basically summarises all the others collected on this matter: “Jihad means removal of oppression for us in Tripoli as much as in Syria. And this has never been addressed in the media… The role of the fighters – mujahidun – is that of making violence secret, as well as the choice of it, to uproot the causes of injustice.” Jihad is portrayed by Ahmed as a very important cause and a challenging task, which requires high levels of accountability acquired by an individual in specific armed groups. He continues by saying:

“The Islamic State is much more easily accessible to potential fighters than al-Qaeda… In fact, to fight with a group you need to be trusted: the fighter’s accountability in the armed group that he desires to join is always an aspect that is taken for granted by journalists, whereas the process of joining an armed group and fight Jihad is much more challenging than expected. It requires a huge effort coming from your inner self. Only some people would be able to accomplish a project of justice.”

With the benefit of hindsight, three factors facilitating the participation of fighters in the so-called Jihadistst groups in Syria are identifiable. Individual vulnerability, often connected to family reasons, like injustice undergone by one of the family members in the past, or even lack of self-confidence and search for a renewed and more assertive Self; social support, which is strongly guaranteed by the armed group one joins, altogether with a supposedly clear-cut ideological worldview, which easily offers solid identities to rely on and life achievements; and, last but not least, the broader and variegated category of contingency, including individual vulnerability and social support mentioned above. Contingency, which is underestimated in part of the literature in favour of intentionality, is able to induce people to take extreme choices (or seen from outside as such), in accordance with material circumstances.

As already underlined in the vast body of literature on Jihadism, terrorism, and the essentialist concept of “Islamic fighters,” psychological abnormality is very rarely observed because it is deemed difficult to measure and define.31

In the present study, all ex fighters or supporters were defining themselves as “followers of the Koranic Jihad”, and the term “Jihadist” was employed to refer to followers of the Jihadi ideology and worldview by simply marking their faith in Islam and the applicability of the very Koranic term “Jihad,” meant as personal effort and struggle for improvement. Although the researcher observed differing views about the way the interviewees envision the political future of Syria and the shape the statecraft should assume, all interviewees mentioned the fact that, by now, even the “moderate FSA brigades” whom the US support still possess a lamsa islamiyye or sabghe islamiyye”(an “Islamic touch” or “Islamic colour”).

2. The “Why You Joined and Why You Left” Worn-out

In the following accounts, it is possible to identify two main areas of discussion on joining and leaving the fighting: contingency on the one hand, which encompasses individual vulnerability for joining or leaving, the search for social support and the implementation of personal worldviews; and, on the other hand, intentionality, including Jihad as a nationalist (and liberation) cause, a religious cause, a political goal, and as a way of gaining economic assets acquired by fighting. Needless to say, these subcategories, in turn, overlap with each other. It should be observed that the emergence of the division of the Islamic brigades is sometimes contingent and at other times deliberate, stemming from different ideologies deployed on the ground.

Mustafa, 24 years old, originally from the Hama governorate and resettled in Tripoli, joined Jabhat an-Nusra, “as it was the first brigade [he] came across on [his] way [from] Syria when [he] arrived in ‘Arsal… [he] was already in touch with some of the fighters via Twitter.” After the clashes between Nusra and the FSA in the Lebanese border town,32his friend died before his eyes during bloodshed. Mustafa decided to leave, “maybe out of fear for [himself], or compassion for his [friend’s] family” or his own, fearing he may suffer the same fate. In this case, what resulted from the “Jihadist experience” was neither the often discussed sense of guilt for his own survival,33which he would consequently have wanted to expiate by continuing to fight, nor a desire for vindicating his friend’s life by fighting the enemy. In this account, contingency plays the largest role in providing the reasons why he joined and left Nusra. In addition, individual vulnerability to further suffering contributed to his decision to leave in the wake of his friend’s death.

Fathi, a Syrian man in his forties from Aleppo, joined Nusra believing “it is the only effective thing you can do to liberate Syria”. He noted, “I would say the love for my homeland was the main reason”. Fathi used words like wataniyye (“sense of national belonging”) and tahrir al-balad (“liberation of the country”) to describe his “whys”. Fathi left because he wanted to raise a family,34and that was not feasible while fighting:

“The only fighters who bring the family with them are those with the Islamic State, as they are like a state indeed, owning infrastructures. We cannot do that […] brigades are always on the move. We lose territory as soon as we take it, where would a family lead the life they deserve? It wasn’t feasible…”.

In Fathi’s story, it is interesting to notice how, while joining the battle in Syria to implement his worldview, he eventually sought out for social support by quitting the fight, as he desired to create a family of his own. Nevertheless, Fathi asserts that he still believes in the cause of carrying on an armed resistance against the Assad regime, but his life choices came to a crossroads and he was forced to decide. This account confirms the scholarly view according to which the sense and practice of membership in a group shadow individual life and deprive it of its moral primacy.35 So to speak, undertaking violence is seen as a “sub-product of collective action”.36Fathi rebelled against this process. Even though a segment of the scholarship tends to view radicalisation as a psychological individual process - in which group ideology still plays an essential role - the material circumstances and the root causes of engagement with armed groups are often de-emphasised.37 Processing research data without considering causes and circumstances entails the risk of making the “Islamist radicals” arbitrarily appear as rebels without a cause.38

Fathi’s choice seems to rebel to the “deindividuation” process of the Jihadist fighter, as, according to this theory,39the individual does not respond any longer to one’s own desires, but rather those of the group he decides to belong to. This points to the importance of averting the homogenisation of fighters and their views under the reifyied label of “terrorism”, to which psychology seeks to offer multiple answers.

Amin, a Lebanese ex-fighter, passed to Nusra after joining the FSA. His reasons seem to reveal his desire to avenge the deaths of his loved ones, “tortured and detained for years in Assad’s prisons,” and to acquire a role in life other than that of a father, since he is unable to have kids.40 An increased sense of control and personal agency, involved in the act of joining an armed “liberation”41group - and, in this case, not achievable in the possibility of becoming a father - can in fact contribute to such a choice.42 Amin joined with the explicit purpose of killing prisoners:

“Well, when you do it out of revenge, you don’t take any glory by imprisoning people. And it’s what I used to do when I was with the FSA… In the Nusra Front I would have been able to kill the assassins and their supporters. In the media, I know I am ‘the terrorist’ because I talk of killing prisoners with no regret, but it’s the reality of war, dear. The truth is that you get used to it, and the violence outrages around you… It’s not that you suddenly step in and you’re coming from peace. It doesn’t work that way… In my case, I was coming from hell, and I was already used to death and to causing it."

In this account, embracing political violence does not seem to be tantamount to escaping ordinary life, as argued by Sageman43who more generally discusses the general concept of extreme political violence as (temporarily) sacrificing one’s own private life in order to achieve political needs. In the face of contingency, deliberate acts of joining and changing brigade are prominent here, although Amin did not want to mention why and how he finally left the fighting.

Hamed, a Syrian refugee from Homs, and brother in law of an Islamic State fighter in the ar-Raqqa countryside, to the question about whether fighters join for economic purposes responded that economic ambition is actually not a common reason:

“When you fight you don’t lead a normal life… As far as I know there are highly ranked fighters who get up to 2,000 USD per month, but once you become a martyr (shahid), the money isn’t left with your family44… See? Not too many reasons to fight for earning a fortune.”

With similar views, Amin mentioned the case of a wealthy Lebanese shop owner in Tripoli, a happily married father and breadwinner for five kids, who became a suicide bomber in Syria after getting in touch with Islamic State fighters via social media.

In this regard, Sageman’s concept of “Global Salafi Jihad” is not only defined as a “threat to the world” that should be eliminated concertedly, but also as a phenomenon that is created by western policies toward the Muslim world,45 and the lack of employment in the Middle East perfectly meets with this western creation. Although it can confidently be said that fighting is not undertaken for money only, underemployment, rather than poverty per se, can still be seen as a further reason for joining the fighting in Syria, as some among the fighters are educated, like the interviewees of the present study.46

Mohammed, a Lebanese 50-year old man who highly sympathises with the Syrian opposition fighters after spending nine years in Hafez al-Assad’s prisons, reasserted the necessity to overthrow the Assad regime while showing me the pictures of other family members who had been victims of Syrian oppression, and identifying Jihad as the only instrument that can serve that cause. “It’s like a parent with his child… he thinks he’s the best [child] ever. And, likewise, I think Jihad is the best way of managing life now. What should we have done in front of the indifference of the international community, which helped to create the Islamic State… all in cahoots with Iran”. Despite this mutual politics of blame - for which Iran and its allies (mainly Syria and Lebanese Hezbollah) accuse the “West” for having created the Islamic State, and, similarly, the Syrian opposition and its sympathisers rather accuse Iran for that – local political history stands out as the primary cause of the “Jihadist phenomenon” in Syria, as it combines Northern Lebanese and Syrian predicament historically grown in the bosom of Islamic movements, the only actual opposition to the western-founded statecraft in Syria.47

Contradicting those who depicted Jihad as a “political thing” entrenched in Lebanese-Syrian history, ‘Omar,originally from Idlib and brother of a Nusra fighter who died as a martyr in Homs while fighting against Assad’s army, rather contended that:

“There’s no one fighting for the nation or the liberation of Syria nowadays… It’s all about religion now. Don’t believe anyone. The reasons are connected to our belonging, our confessional identity. This started with Hezbollah and Iran: they were also foreign powers killing people in Syria… but no one condemned them. They just blamed the Sunni Jihadists defending their survival on the ground. The truth is that everyone wants to speak with us and then blame us because we pray the holy Koran. It’s our Islam that makes the difference, don’t you think? Many of us have spent more than 10 years in prison… I think what we’re doing is totally normal then. How do you react to continuous oppression? You even forget that Nusra don’t kill people randomly… we’re not like the Islamic State. War prisoners are also killed by the National Army in Syria, and it has always been like this in the history of warfare!”

Likewise, ‘Abdallah, a Lebanese in his 20s,suggested studying the Holy Koran more in depth to know what is behind Jihadism and their ideology, further shedding light on the illusive tension between religion and politics as explanatory tools of current Jihadism:

"You keep asking about our lives, families, professions, stories of family migrations, but I think you should simply study our religion more in depth and listen to what God said if you really want to understand what is going on. We see Jihad as a result of our oppression, any religion would justify this… and this is why the Islamic State is not Islamic! The Holy Koran doesn’t say to kill children and women at will. Assad and Hezbollah are killing people and no one studies them in Syria… If your family died because of a political regime, I really want to see if you would remain there with your arms folded… I’m sure you’d start doing justice by your own!”

It is important to note how a more nuanced explanation of radicalisation48 should neither over-emphasise the role of religion in undertaking political violence, nor discount it.49 Its role is also difficult to analyse, or even nonsensical as a separate element, due to its symbiosis with the lived experiences of politics and cultural habitus. Nevertheless, engagement in armed groups points, by all means, to an “Islamisation of radicalism” - even in a merely normative way - rather than to a “radicalisation of Islam” which cannot subsist tout court, as it would reinforce essential forms of religion talk, unresearchable and unassessable on the ground.

Walid, a Lebanese man who was speaking affectionately of his neighbour who went to Syria to become a martyr a few months earlier, expressed his perplexity about “Westerners” asking for the reasons of “radicalisation.” He stressed the intentionality of the act of fighting and embracing a specific ideology among the several options:

“There will never be a fixed set of reasons… Why should this be ‘extremism’? Stop bombing us, and we’ll be able to negotiate with the Assad regime. We’re just attacked instead, because, from outside, all ideologies look the same. Qaeda is not the Islamic State. Ideologies of fighters were diverse in Syria since the early formation of the FSA. Also the political project we pursued wasn’t imagined in the same way. They talk of extremism, and they are the ones who didn’t do anything at all to end all the suffering caused by Assad. The indifference of the international community caused all this, or we wouldn’t even have taken up the weapons. Now why shouldn’t I have the right to fight if I feel like?”

Mohammed, by the same token, restated the differences between the armed brigades in practice and thinking:

"It is worthwhile to join a brigade that doesn’t compromise with the Syrian regime… several groups of FSA eventually did it, as well as the Islamic State, which is a product of the regime straight away. (Do you want evidence? Why is it never heavily bombed like other groups?) So, if you join, you must do it with a brigade that is effective, and many guys going to Syria don’t take this into account.”

Similarly, Wa’el, a Syrian ex fighter with Jund ash-Sham, argued that he revalued the FSA only after fighting against it in the Damascus countryside, and after seeing the FSA allying with his brigade against the Assad regime, proving not to be corrupt like others. Mustafa contended the artificiality of the brigades’ division, as “the brigades are several because they are divided by the spies of the Syrian army in the effort to destroy [their] cohesion. This [has] guaranteed the regime’s survival!”.

Overall, all interlocutors agreed about the most frequent methods of recruitment by one of the brigades in Syria. Among several others, the main channels seem to be social media like Twitter, WhatsApp, and Facebook, in addition to having pre-existing friends and kins in a particular brigade,50and, as mentioned, the contingency of joining the first armed group you encounter on your way from Lebanon to Syria (although less probable). In this framework, the roles of contingency and intentionality in “making it happen” obviously intertwine in a complex way, which can be researched only by analysing single empirical cases.

3. Tracking Perspectives and Perplexities Beyond War

One of the issues that is widely discussed in international media and academic environments today is to what extent this process of radicalisation will be resilient or, by contrast, will gradually become integrated into society and normalised in other forms, by decreasing its violence and extremist potential.

In this regard, Fathi said that, “when the war ends, everyone will want to go back to their family and lead a normal life. I don’t see any other purpose for fighting once justice is re-established”. Similarly, Wa’el argued that “no one can really desire war forever.”51

As an ex-fighter, Amin interestingly answered that no future perspectives are influencing their lives now,

“… all what you believe in is the need to fight who oppressed you, until his annihilation. Some of us are still engaging with future resolutions while fighting, as I did… in that case you end up thinking of what is awaiting you outside. Material circumstances eventually push you to leave the fight. But this rarely happens. Even the mutilated, most of the time, get a bone replacement and go back fighting. After the return we’re still persecuted. You never abandon a way of thinking if your family got mad, killed, and tortured by a regime… Some of the ‘returnees’ who got subjected to the violence of the Syrian regime later committed suicide”.

Beyond the diverse character of the life perspectives that each of the interviewees may have, the interlocutors mostly showed perplexity about the external – basically “western” – way of conducting studies on political violence and essential forms of “extremism”. On this purpose, Mohammed, as well as ‘Abdallah and Walid, mentioned the massive presence of NGOs that, from the interviewees’ perspective, seek to implement their cultural views and activities in Tripoli, somehow trying to prevent the local and refugee youth from joining the armed groups in Syria. Mohammed argued that

“International NGOs lack direct access to local communities and end up addressing families that would never send their kids to fight in Syria, or that have not been oppressed from a political viewpoint. How can they imagine having tangible results? Children develop the same culture as their parents.”

He then highlighted how international NGOs are not even able to identify the causes of violence and, therefore, implement projects that do not seem to reflect the needs on the ground.

"It’s not about lack of schooling or employment. They don’t want to see that it’s oppression and religious identity threats that induce people to fight… the Assads used the Alawites52 as weapons, and no NGO deals with this!”.

Concluding Remarks

While Jihadist insurgencies have always been approached and discussed by scholars in the sociological framework of “deviance”, in light of these interview accounts, it is necessary to adopt the analytical instruments of “normalcy” and ordinariness to understand the environment in which ideology and life choices are made and developed. The above mentioned accounts foreground how the imaginary linear structure of analysis for the engagement and disengagement of a fighter or ideological supporter fails to reflect a reality that rather resembles a cyclic spiral: the interlocutors’ thinking and subsequent acts seem to be still connected to their original choices, generating a cyclic process significantly guided by contingency. Jihadism cannot be used as a holistic explanatory concept. This small research study on the interface between Tripoli and the Syrian battles proves how some rehabilitation programmes and scholarly analyses may be flawed in conceiving Jihadist fighters and supporters as affected by an “illness to be treated”, disconnecting Jihadist tendencies from political causes and historical legacies.

Humiliation and frustration are recognised by scholars as the first causes to push people towards extremism. However, non-conflict motives like seeing the suffering of others, manhood, and heroism, have also been taken into account by the scholarship. If Speckhard calls for a return to the origin of the individuals’ trajectory in order to stop the phenomenon of violent extremism,53 then the latter in Tripoli is not addressable by rehabilitation programmes. The latter would not “sort out” the local forms of political violence even if they did not ignore the political past of the city - issue which is instead very typical of these programmes. There can be no rehabilitation of what is not politically addressed and recognised. The historical de facto de-institutionalisation of Tripoli’s society and of its multiple ways of expressing political dissent rules out any chance for ad hoc restorative practices. In light of this quick study, even the current desire of turning psychological failures into success stories turns out to be illusive and fictive.

For the Syrian and Lebanese interviewees, it is the time spent in conflict-ridden Syria and oppressed Lebanon, infiltrated by Syrian intelligence and chronically subjected to the Assad regime’s political decisions, that “radicalises” people and sensitises them to their conception of social justice. At the same time, the lack of military intervention from the international community to end Assad’s mandate made these individuals suspicious and dutiful towards their own cause and the need for fighting.

The interviewees expressed that their intention and actual will to fight are mere efforts made to liberate their countries, liberating Lebanon from past and current humiliation and Syrians from the Assad regime-caused predicament: causes that are mostly presented as one. Indeed, the interviewees underlined that they did not fight or support the fighters in any other foreign conflict. Unlike the “Islamic State,” enlarged by the presence of foreigners and viewed by the interviewees as an external phenomenon tout court, my research interlocutors stressed that they fought - or support the fighting - for the sake of the armed Syrian opposition, imbued with a politically motivated Jihad.

The interviewees’ responses seem to suggest that researchers should rather focus on the actions and choices of the “international community” – yet illusively conceived as a potential deus ex machina - rather than focusing on the allegedly abnormal circumstances in which Jihad develops.54 It is significant to note that American scholar Lisa Stampnitzky named the proliferation of literature on terrorism55 and the politicised way of carrying out these types of studies – basically aimed at honing US security strategies - “politics of anti-knowledge” which foregrounds arbitrary and essentialist conceptions of political violence.

This interview-based study has been able to unearth the political dimension of the claim to the “right to Jihad” and emphasise the injustice of the “international community” in rejecting such a right to fight. Despite this, the limitations of this study particularly reside in its inability to unravel the choices of the five interviewees who decided to join the armed groups in Syria with respect to whom did not take up the weapons. In fact, the study struggles to identify what factors and circumstances prevented the other five from combating in war, considering that all interviewees shared equivalent political views in regards to the Syrian regime and its necessary departure. A larger ethnographic study would certainly provide a deeper analytical understanding of such queries. Nevertheless, in light of the accounts collected from Jihadist ex fighters and supporters, this study can still confirm that the acquisition of “extreme” views has a weak relationship to the turn to political violence. In this case, the Assads’ oppression is not only marking local political history. And violence is not simplistically used in retaliation. Yet it is employed here as a flagship narrative which is still able to identify ongoing predicament and generalised disaffection.

Ultimately, this primary study has sought to demonstrate how there is no linear and unilateral progression from “extremist beliefs” to violence. Hence, the concept of “failure,” as formulated and thought by rehabilitation programmes whenever their beneficiary does not become “de-radicalised” despite their efforts, is flawed both in its logic and in its practice. Yet, the mainstream way in which current rehabilitation programmes – and NGOs partaking in similar disengagement practices - seem to address the issue along similar flawed lines. What should be “radical” is rather a rethinking of the deployment and applicability of such rehabilitation programmes, as well as the rationale behind their implementation which is largely at the mercy of the security agendas of domestic and international power holders.

In the range of assorted reasons for engagement in armed groups - from repression to social isolation, from frustration to group apprenticeship - the constant transformation of life purposes and individual narratives still has a long way ahead to be properly unpacked and be dealt with as inseparable from the proliferating studies on terrorism and extremism.

Meanwhile, the cyclic appearance of institutional and deinstitutionalised political violence keeps casting new questions of how to understand power, survival, and knowledge. While the analysed accounts seem to voice violence as an instrument for their ultimate form of survival, NGOs and scholars that tackle disengagement and rehabilitation of ex fighters should question to what agendas and political premises they owe their foundation as well as their own survival.

Bibliography

Omar Ashour, “Post-Jihadism: Libya and the Global Transformations of Armed Islamist Movements”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 23, No. 3, Taylor & Francis, 2011.

Kate Barrelle, “Pro-Integration: Disengagement from and Life after Extremism”, in Behavioural Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2014, pp. 129-142.

Andrew Beatty, “Emotions in the Field: what are we talking about?”, in Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) 11, 2005, pp. 17-37.

John Chalcraft, The Invisible Cage. Syrian Migrant Workers in Lebanon. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2009.

Donatella della Porta, Social Movements, Political Violence and the State. Cambridge (UK), Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Franco Ferracuti, “A Socio-psychiatric Interpretation of Terrorism”, in The Annals of the American Academy, No.463, 1982, pp. 129-140.

Tine Gade, “Tripoli (Lebanon) as a Microcosm of the Crisis of Sunnism in the Levant”, paper presented at the annual meeting of the British Middle East Studies Society (BRISMES), London School of Economics (LSE), 26-28 March 2012.

John Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism, NYC, Routledge, 2005.

John Horgan, “Deradicalization or Disengagement: a Process in Need of Clarity and a Counter-Terrorism Initiative in Need of Evaluation”, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2008.

Lene Kuhle and Lasse Lindekilde Radicalisation among Young Muslims in Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark, Centre for Studies in Islamism and Radicalisation, January 2010.

Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, Friction: how Radicalization happens to Them and Us, New York, Oxford University Press, 2011.

Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Marc Sageman, “The Stagnation in Terrorism Research”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Taylor & Francis, pp. 1-16, March 28, 2014.

Hamed el-Said, Deradicalising Islamists: Programmes and Their Impact in Muslim Majority States, The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) Report, January 2012.

David H. Schanzer, “No Easy Day: Government Roadblocks and the Unsolvable Problem of Political Violence: a response to Marc Sageman’s ‘The Stagnation in Terrorism Research’”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Taylor & Francis, March 28, 2014, pp. 1-5.

Mark Sedgwick, “The Concept of Radicalisation as a Source of Confusion”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 22, 2010, pp. 479-494.

Mark Sedgwick, “Jihadistsm, Narrow and Wide: The Dangers of Loose Use of an Important Term”, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 2015, pp. 34-41.

Michel Seurat, Syrie, l’état de Barbarie, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. Proché-Orient, 2012.

Isabelle Sommier, “Engagement Radical, Désengagement et Radicalisation. Continuum et Lignes de Fracture”, in Lien Social et Politique, no. 68, 2012, pp. 15-35.

Ann Speckhard, Talking to Terrorists, Advanced Press, 2012.

Lisa Stampnitzky, Disciplining Terror: how Experts and Others invented Terrorism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Charles Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution. Reading, UK: Mass., Addison Wesley,1978.

Graeme Wood, “What ISIS really wants”, in The Atlantic, March 2015.

- 1. In drafting this paper I am indebted to Amaryllis Georges, who consistently provided me with thought-provoking literature on political violence and extremism. I am also indebted to my three gatekeepers in Abu Samra, Bab at-Tabbaneh, and Zahriye, who made this small study possible.

- 2. It is imperative to stress that, in the specific case of this study, Lebanon has not undertaken rehabilitation programmes. Moreover, only Jabhat an-Nusra’s ex fighters among the interviewees would probably be suitable for these programmes, in that what is left of the multi-faced Free Syrian Army, despite its still present variegated “Islamic character,” has generally not been considered a product of violent extremism in official western diplomacy. The purpose of this paper is therefore to explore the likely contradictions of rehabilitation programmes by aligning with a segment of the scholarly literature not directly meaning to “heal” the social context at hand. Yet, the research findings can inform us on the very practically flawed and politically biased nature of such programmes’ rationale.

- 3. Isabelle Sommier, “Engagement Radical, Désengagement et Radicalisation. Continuum et Lignes de Fracture”, in Lien Social et Politique, no. 68, 2012, p. 17.

- 4. Hamed el-Said, Deradicalising Islamists: Programmes and Their Impact in Muslim Majority States, The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) Report, January 2012, p. 1-2.

- 5. John Horgan, “Deradicalization or Disengagement: a Process in Need of Clarity and a Counter-Terrorism Initiative in Need of Evaluation”, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 2, No. 4, 2008.

- 6. Seurat speaks of 47.6% of people coming from outside Tripoli. Michel Seurat, Syrie, l’état de Barbarie, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. Proché-Orient, 2012, p. 246.

- 7. Michel Seurat, Syrie, l’état de Barbarie, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. Proché-Orient, 2012, p. 240.

- 8. Italian scholar Donatella Della Porta interestingly breaks down such pull factors by forwarding the two categories of “facilitating factors”, first inducing the individual to join armed groups, and “precipitating factors”, which constitute the last straw in leading the individual to engage with political violence. Donatella della Porta, Social Movements, Political Violence and the State, Cambridge (UK), Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- 9. Clark McCauley and Sophia Moskalenko, Friction: how Radicalization happens to Them and Us, New York, Oxford University Press, 2011.

- 10. David, H. Schanzer, “No Easy Day: Government Roadblocks and the Unsolvable Problem of Political Violence: a Response to Marc Sageman’s ‘The Stagnation in Terrorism Research’”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Taylor & Francis, March 28, 2014, p. 3.

- 11. For more details on Jabhat an-Nusra, read: https://civilsociety-centre.org/party/al-nusra-front [last accessed on 01 December 2015]

- 12. Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- 13. Mark Sedgwick, “The Concept of Radicalisation as a Source of Confusion”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, No. 22, 2010, p. 483.

- 14. For more details on the Islamic State (IS), read: https://civilsociety-centre.org/party/islamic-state-daech [last accessed on 01 December 2015].

- 15. John Chalcraft, The Invisible Cage. Syrian Migrant Workers in Lebanon, Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2009

- 16. This is the reason why Lebanon has been seen as a puppet country after the 1989 Ta’if Agreement, officially ending the civil war.

- 17. Tine Gade, “Tripoli (Lebanon) as a Microcosm of the Crisis of Sunnism in the Levant”, paper presented at the annual meeting of the British Middle East Studies Society (BRISMES), London School of Economics (LSE),

- 18. Idem., p. 16.

- 19. Idem., p. 31.

- 20. Idem., p. 42.

- 21. Idem., p. 44.

- 22. The local Sunni community has also founded a Committee aimed at pressuring the government and local officials to re-open the airport (named René Mou‘awad Airport). The goals and principles of this Committee are easily findable on several social media. The fact that the airport’s opening to civilians has not been sanctioned yet is locally interpreted as a plot against the Sunnis of Lebanon. The main argument used by those who oppose the reopening is the further sectarisation of infrastructures and resources, implicitly referring to the fact that Hezbollah practically controls the Beirut airport. Furthermore, some opinion-makers and local communities, especially in South Lebanon, denounce such a request by stating that the airport would be used as a US airbase. The reopening would sanctify American imperialism in the country.

- 23. Michel Seurat, Syrie, l’état de Barbarie. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. Proché-Orient, 2012.

- 24. Mainly Hezbollah, owning several NGOs in Lebanon and boasting to have woven a strong network of welfare providers

- 25. It is worth highlighting that, whilst the research participants have not been sampled on the grounds of their past family or individual experiences with the Syrian regime, they have rather been selected on the basis of their physical or moral participation in one of the armed groups presently fighting in Syria.

- 26. John Chalcraft, The Invisible Cage. Syrian Migrant Workers in Lebanon, Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press, 2009.

- 27. Andrew Beatty, “Emotions in the Field: what are we talking about?”, in Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.) No. 11, 2005, pp. 17-37.

- 28. Mark Sedgwick, “Jihadistsm, Narrow and Wide: The Dangers of Loose Use of an Important Term”, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 2015, p. 35.

Mark Sedgwick, “Jihadistsm, Narrow and Wide: The Dangers of Loose Use of an Important Term”, in Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 9, No. 2, April 2015, p. 35. - 29. Idem., p. 39.

- 30. Omar Ashour, “Post-Jihadism: Libya and the Global Transformations of Armed Islamist Movements”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 23, No. 3, Taylor & Francis., 2011, p. 379.

- 31. Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004; John Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism, NYC, Routledge, 2005.

- 32. The clashes between Jabhat an-Nusra and the FSA in the town of ‘Arsal do not seem to have been reported in the international media to the same extent as those in Daraa or Rastan. Apparently this small-scale conflict happened over 2014, as reported by the interlocutor.

- 33. Ann Speckhard, Talking to Terrorists, Advanced Press, 2012.

- 34. This is quite a common and attractive pull factor to disengage individuals from violent extremism. Kate Barrelle, “Pro-Integration: Disengagement from and Life after Extremism”, in Behavioural Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2014, p. 132.

- 35. John Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism, NYC, Routledge, 2005.

- 36. Charles Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution, Reading, Mass., Addison Wesley,1978.

- 37. Marc Sedgwick, “The Concept of Radicalisation as a Source of Confusion”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, 22, 2010, p. 481.

- 38. Lene Kuhle and Lasse Lindekilde, Radicalisation among Young Muslims in Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark, Centre for Studies in Islamism and Radicalisation January 2010.

- 39. John Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism, NYC, Routledge, 2005.

- 40. This confession to me, a female researcher, actually surprised me in that it rhetorically affects his “maleness”, whilst his choice of combating could have been interpreted as an attempt to claim back his machismo.

- 41. It is personal opinion of the author that the interviewees paradoxically seem to have lost the sense of how the battles are deployed on the ground. The number of times that the Syrian opposition brigades fight each other rather than the Assad forces can no longer be counted. Many are the cases in which the current battles seem to be a power struggle over specific territories rather than the liberation of the whole country – which, by now, would certainly not be well-bounded.

- 42. John Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism, NYC, Routledge, 2005, p. 137.

- 43. Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- 44. The researcher did not have the chance to empirically ascertain this datum.

- 45. Marc Sageman, Understanding Terror Networks, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

- 46. It is however interesting to see how the Syrian refugees in Lebanon who do not support the Jihadi ideology and the extreme forms of violence adopted by the variegated armed opposition in Syria, rather tend to interpret the “Jihadist phenomenon” as a “money issue”, since most of the fighters are murtaziqun, “mercenaries” (Informal conversation with A., N., and R. in Beirut, May 2015).

- 47. Michel Seurat, Syrie, l’état de Barbarie, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. Proché-Orient, 2012.

- 48. This term is used in full awareness of the scholarly scepticism around it: if radicalisation is not an absolute phenomenon with standardised traits, it also presents limitations in its relative aspects. Indeed, if radicalisation indicates a “movement along a continuum of organised opinion, where does the moderate section of the continuum lie”? (Mark Sedgwick, “The Concept of Radicalisation as a Source of Confusion”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 22, 2010, pp. 481).

- 49. David H. Schanzer, “No Easy Day: Government Roadblocks and the Unsolvable Problem of Political Violence: a response to Marc Sageman’s ‘The Stagnation in Terrorism Research’”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Taylor & Francis, March 28, 2014, p. 3.

- 50. Marc Sageman, “The Stagnation in Terrorism Research”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Taylor & Francis, March 28, 2014, p. 3.

- 51. In this regard, there is a sizeable difference from the Islamic State’s thinking, for which killing in battle or outside of it is indifferent, as the ideals you are killing your enemy for remain the same. Thus, there is no clear-cut difference between in bello and outside of war; being a mujahid entails an existential status. This view is further fed by what is seen as a ‘’war on Islam’’ with the 2003 American occupation of Iraq, and the present intervention in Syria only conducted against the Islamic State and yet not against the Assad regime. In the Islamic State’s logic, there is the conviction that war never ends, since such a struggle is part of one’s own religion and life. Graeme Wood, “What ISIS really wants”, in The Atlantic, March 2015.

- 52. Alawites is the confessional sect of the Assads in Syria, and, as such, for complex historical and political reasons, majorly tend to support the Syrian regime or, however, see the latter as the only anchor of safety and certainty. 4.7% of Northern Lebanese population are Alawite, living in 12 villages in Akkar. The Alawite community is also living in the Tripoli neighbourhood of Jabal Mohsen, in chronic conflict with the Sunni district of Bab at-Tabbaneh, ironically divided by Syria Street. This microcosmic conflict received great media and scholarly attention due to its connection to regional politics (Syrian Army versus Palestinians led by Yasser Arafat, driven out of Lebanon in 1983; and Panarabism versus a French-created Lebanon of privileged elites).

- 53. Ann Speckhard, Talking to Terrorists, Advanced Press, 2012.

- 54. Franco Ferracuti, “A Socio-psychiatric Interpretation of Terrorism”, in The Annals of the American Academy, No. 463, 1982, pp. 129-140. And John Horgan, The Psychology of Terrorism, NYC, Routledge, 2005.

- 55. Between September 2001 and 2008, 2,281 books with terrorism in the title have been published.

Estella Carpi is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Migration Research Unit, Department of Geography, University College London (UCL), where she works in the framework of a European Research Council project on Southern-Led Responses to Displacement from Syria, with a focus on Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. She is presently a Visiting Researcher in the Department of Sociology at Koç Universitesi-Istanbul. She received her PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Sydney (Australia), with a study on the social response to humanitarian assistance provision in contemporary Lebanon. After studying Arabic in Milan and Damascus (2002-2008), she worked for several research and academic institutions in the Middle East, such as the New York University (Abu Dhabi), The Centre for Social Sciences Research and Action (Beirut), Trends Research & Advisory (Abu Dhabi), UN-Habitat (Beirut), the American University of Beirut, the United Nations Development Program-Egypt (Cairo), and the International Development Research Center (Cairo), mostly focusing on forced migrations, humanitarianism, and identity politics. She has lectured extensively in the Social Sciences in Italy and Australia. She has been selected as a 2020-25 Global Young Academy member. It is possible to read her work in international academic journals such as the Journal of Refugee Studies, Third World Quarterly, and Middle East Critique. Estella is also the author of Specchi Scomodi. Etnografia delle Migrazioni Forzate nel Libano Contemporaneo, published in Italian with Mimesis (2019). She loves conducting research on the places that have been part of her life.

Wordpress: www.mabisir.wordpress.com

Southern responses:https://southernresponses.org/

Twitter:https://twitter.com/estycrp